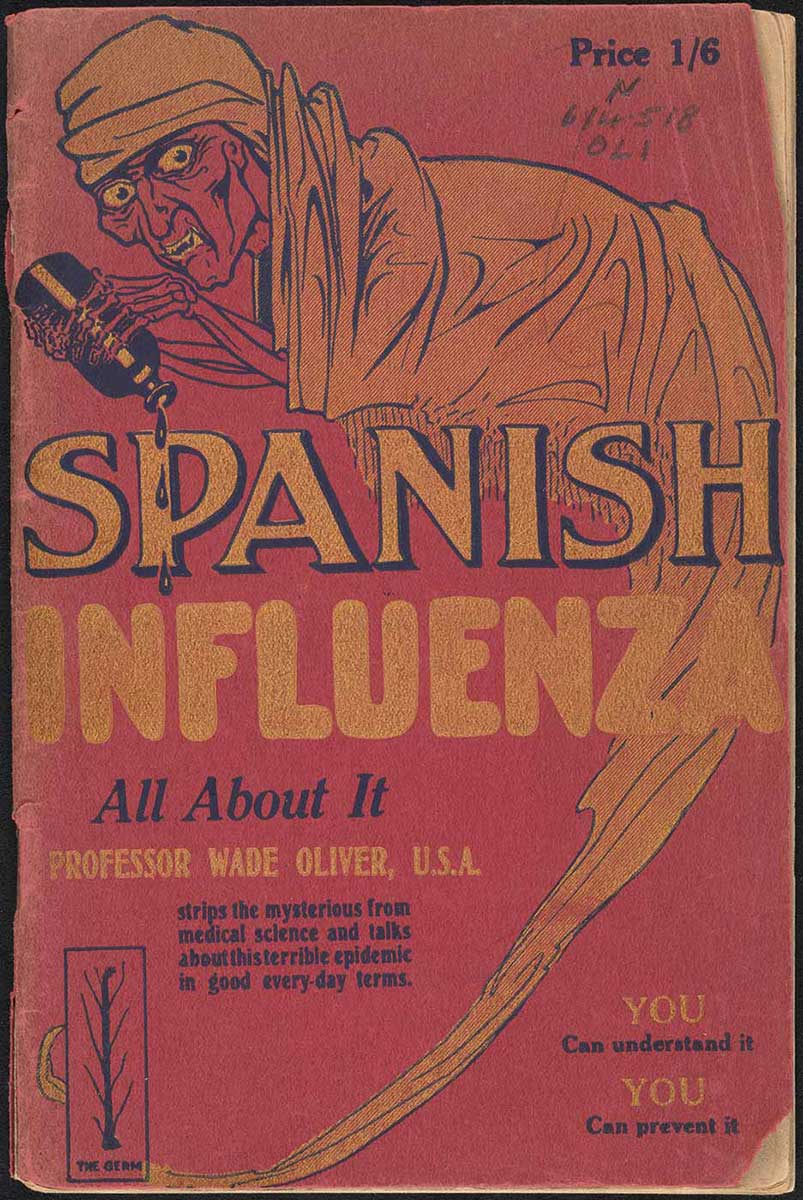

Drastic century-old measures against the coronavirus had not prevented 800 deaths by early February — the total then jumping to nearly 1,000 in a day. A look at the great epidemic of 1918-9, the misnamed “Spanish flu”, shows that modern medical science has not produced any easy answers since that time.

Bulletins on the weekend of 8-9 February reported many new cases of the disease, 37,200 in China – with most of the 800 deaths still concentrated there – and huge international impacts. That weekend the second plane-load of Australian citizens was brought back from the stricken city of Wuhan, flying into Darwin; they’d have two weeks of quarantine; there were 15 sufferers in Australian hospitals, and among Australians stranded overseas, some 235 quarantined on cruise ships.

The disease gets into the category of terror epidemics of the past, because it is highly infectious, being called both “relatively mild” compared to some other flus, but also “deadly”.

CONTROL MEASURES IN FORCE

This list of control measures applied by public authorities shows the level of concern:

- emergency declarations;

- closing of traffic across borders;

- the isolation of cities;

- compulsory isolation of possible carriers;

- shutting down of gathering points, like theatres or public transport;

- wearing of masks;

- hygiene measures involving spraying of disinfectants;

- stiffened penalties for breach of regulations; and

- call-up of medical staff and volunteers.

That list, true for this year, actually is taken from a study of the Spanish flu crisis in the Australian city of Brisbane in 1919.

The study’s author Matthew Wengert sorted through piles of archived documents, photographs and newspaper records to produce a book about 1919 that is eerily resonant now — called City in Masks.

INFLUENZA THE BIGGEST KILLER OF WORLD WAR I

The Spanish flu was the major killer of World War 1. It infected some 500 million people, one-third of the world population, killing at least 20 million — many estimates running to 50 million. There were 20 million deaths directly linked to the war, half being soldiers, and 20 per cent of those soldiers died from the Spanish flu and other diseases.

At the end of 1918 Australia waited anxiously for the return of its troops and for the arrival of the disease that would come with them — a sinister virus so attuned to barracks conditions, it killed mainly young adults, especially males. The troop transports circling the globe provided an equivalent impact to air travel in the following century — mass arrivals from infected parts.

The Federal and State authorities in Victoria delayed making an official declaration of the obvious when it struck in Melbourne, in January 1919, losing some time with their control measures. When it appeared later that month in New South Wales, wearing of face masks was made compulsory. Queensland closed its southern border, trapping hundreds in Sydney and in quarantine camps along the frontier. The set quarantine period then was one-week.

WHAT STRATEGY FOR HUMAN SURVIVAL?

The flu pathogen was well understood, with the best available strategy decided on: to keep patients alive long enough for their antibodies to prevail and for the disease to run its course in the population. People in Brisbane, a city then of just 190,000 souls, were aware of appalling losses in other countries — like India, with over 10 million deaths. Their own resources were stronger and, on the evidence produced by the historian Wengert, they performed feats of civic organisation to reduce the terrible impact.

Hospitals lacked the viral laboratory tests done today for quick diagnosis, and could not hold out for an anti-viral vaccine. The city had over 20,000 doses of a bacterial vaccine, which it was hoped might help in some way, although that idea was immediately put down in a special edition of the Australian Medical Journal. There was a rush on improvised inoculation centres, 250 turning up on the first day of availability. Along with the vaccinations, masks and isolation, prospective patients were given an antiseptic throat spray and sent to an “inhalatorium”, to breathe in steam infused with zinc sulphate, on the theory that the noxious fume might dispel germs. Maybe most effective was the knowledge that the virus transferred in droplets or from surfaces, bringing on a public education campaign against spitting, open coughing and unwashed hands — again, like now.

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/P27TCSHMUZBBJBJNRQ2ASDSDFA.jpg)

Preparing for the inevitable, two temporary hospitals were set up at the "Exhibition", the Brisbane showgrounds and a Catholic boys' school. Later creches were opened for children whose parents were sick, or still in the Army. The Children’s Hospital had a double task, dealing with a diphtheria outbreak. In a general hygiene drive, rats were eradicated and Council teams sent out to spray the streets.

DOING EVERYTHING THEY COULD

Waiting, they did everything they could and then the month of May 1919 became a classic "trial by pestilence" — an ordeal experienced by cities globally over centuries. The disease which first hit at the end of April, arrived with hundreds of soldiers on troop ships and passengers on other ships put into quarantine on Moreton Bay. Against State Government objections, the Commonwealth had the soldiers disembark into a quarantine camp at Lytton near the port.

In a community mobilised for crisis, a heavy burden fell on women, called on to volunteer in the newly set up Women’s Emergency Corps. Where the city lacked some of the tools of modern medicine, the Corps did deploy latest technology, especially telephones and motor cars, several handed over by their owners. The relief operation was based on the organisation of the city’s small municipal councils, with the Lady Mayoress or other woman community leader in charge. Street patrols were mounted, provided by sports clubs, or teachers once the schools were closed, sometimes even children.

Householders had two cards to show in their window if needed, for the patrol to see: 'Food' and 'SOS'. Community kitchens run by churches or the Red Cross provided simple fare, such as beef tea and mutton broth, which volunteers would deliver. If it was 'SOS', volunteers would go in and nurse the patients, to be 'fed, hydrated, cleaned and comforted'.

In repeated cases, they would find a whole family laid up with just a child attending to them. “I’m the only one left,” said one. They made thousands of visits.

PALL OF DEATH

The first patient to die was a seaman buried at Lytton on 1 May. The two main hospitals, General and Exhibition, were handling hundreds of cases; by the middle of the month they were reporting usually three to six deaths at each place, each day. Many medical staff got it, with 80 nurses themselves being treated in hospital on 23 May.

Nine died on the last day of May and the epidemic raged for another week, before starting to subside. Admissions were falling off; on 6 June the Exhibition hospital had its first day with no deaths in a month. Things were back to "normal" enough that they were able to hold a commemorative parade after the signing of the peace settlement, the Treaty of Versailles, on 28 June 1919.

The official tally of deaths in the epidemic stood at 302, out of 9,570 recorded cases — by population, matching the thousands lost earlier in Sydney and Melbourne, among millions in other countries.

BACK TO THE PRESENT

The World Health Organisation says in 2020 there may be some “stabilising” in Wuhan, but not to count on it. With the disease in 25 countries, the WHO is concerned about it getting to places that do not have adequate systems to cope.

The Chinese Communist Party Government gave in to their initial impulse to suppress facts, disciplining Li Wenliang, the doctor who found and told about the disease, and died from it. They have since imposed draconian, but open, measures to try and contain it — one provincial boss even muttering about the death penalty for non-compliers. The spraying, transport blockades, enforced "holidays", go right back to another time, where the measures did work, at unavoidable cost. If they could go back to 1919 and learn from the good burghers of cities in Australia about working with the community, they might do better yet.

Homo sapiens, the most dangerous yet inventive animal, had its war and spawned a new and fatal disease, then deployed the greatest resources, ingenuity and love trying to defeat it. Has it really changed in this last century?

READ MORE: Matthew Wengert (2018), City in Masks. Brisbane, Andalso Books.

Media editor Dr Lee Duffield is a former ABC foreign correspondent, political journalist and academic.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.