The slower the RBA is to cut rates, the bigger the pile-up of economic problems later. Stephen Koukoulas reports.

ONE OF THE MAIN THINGS standing in the way of a more prosperous economy over the next couple of years are the policy decisions of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

Sure, it has delivered a second interest rate cut in this cycle, but it is taking baby steps towards easier monetary policy when big steps are needed to deliver a much-needed pick-up in private sector spending, investment and hiring.

The simple economic checklist in front of the RBA at present shows the reason why even easier monetary policy is urgently needed: to keep people who want a job in a job and to stop inflation falling too far. This can be done by lifting the pace of economic growth back to trend.

Here are the key economic indicators:

- GDP growth is currently 1.3% and when the March quarter data is released next week, it will likely confirm growth still stuck below 2%.

- Annual inflation, across all measures, is within the RBA 2–3% target band. Both the headline and the trimmed mean inflation rate are set to remain in that band for as far as the eye can see.

- The labour market is slackening, with annual wage growth hovering around 3.4%, while the unemployment rate has kicked up to 4.1% as job advertisements and vacancies track lower.

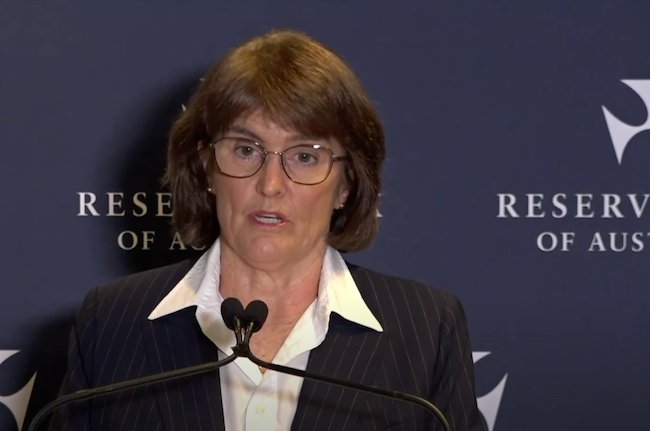

All of this economic news is with interest rate settings "restrictive" as the RBA Governor Michele Bullock noted after delivering the 25 basis point cut on 20 May.

In very simple economic terms, "restrictive interest rates" means that monetary policy is causing households and businesses to spend, invest and hire less as they respond to higher interest rate costs. Money is being diverted to paying interest, which means less for spending elsewhere.

Conversely, a "neutral" level of interest rates, which is estimated in Australia to be around 3–3.25%, is a rate that neither encourages nor discourages extra economic activity from the private sector. This is where official interest rates should be now.

The concept of neutral interest rates is an important benchmark because it shows that official interest rates are around 75 basis points too high.

At her press conference after last week’s interest rate decision, Governor Bullock noted that the Board gave consideration to a 50 basis point interest rate cut. Without giving any specifics as to why this pro-active and sensible proposal was rejected. It means that monetary policy will be too tight for many months to come.

Even if the RBA cuts interest rates by 25 basis points at each of its next three meetings, the rates will not be neutral until the end of September 2025. Even then, it takes at least three to six months for the effect of lower interest rates to have an impact on the economy.

If there is any downside to the current outlook for the economy, interest rates will need to be accommodative or stimulatory — that is, below 3%. Which is why the RBA continues to risk a period of severe economic weakness in Australia with its tardiness.

There is no doubt that the global economy is slowing and at grave risk of weakening markedly under the weight of global trade dislocation resulting from the Trump tariff debacle.

Governor Bullock emphasised this last week when she said:

We see growth in our major trading partners slowing over the remainder of this year and next year…

If the trade outcomes are much worse for the global economy though, we could be facing a much larger downturn in Australia, with implications for inflation and unemployment.

That analysis alone should have locked in a 50 basis point cut.

This is particularly so with no signs of a favourable resolution of the tariff trade war. High tariffs in one form or another will be in place over the next few years, even with the odd compromise and deal with the U.S. Administration.

Until the RBA gets interest rates to neutral, or even slightly stimulatory, the domestic economy will be weaker than need be, inflation will be lower than necessary and the still favourable conditions in the labour market will quickly turn into a problem.

The RBA was one of the last of the major central banks to start the interest rate-cutting cycle — even with last week’s move, it has cut the least.

Money markets continue to price in a series of interest rate cuts by the end of 2025, with a cash rate of 3.1% factored in.

The slower the RBA is to cut rates, the weaker the economy will be and the more it will have to "catch up" to repair the damage, which could be an issue to manage in 2026.

This is why there are a growing number of economists looking for a sub-3% cash rate by late 2025/early 2026.

Stephen Koukoulas is one of Australia’s most respected economists, a past chief economist of Citibank and senior economic advisor to an Australian Prime Minister. You can follow Stephen on Twitter/X @TheKouk.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.