There’s a flight of fancy with some Australian economists and commentators that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) must hike interest rates in the months ahead.

It is a flight of fancy because the RBA knows inflation is set to return to its 2-3% target in the September quarter of 2024 and be entrenched there for the years ahead. It is also acutely aware that a further rate hike would deepen the per capita recession that is already hitting many Australians.

So why do something so damaging to an already fragile economy?

While each of the “rates must be hiked” zealots appear to have a slightly different nuance behind their demands, persistently high inflation is an overarching issue for them.

Such calls for economic austerity rarely, if ever, refer to unemployment, which has already risen from a low of 3.5% in 2023 to the latest reading of 4.1%. The job vacancies data are pointing to it rising to 4.5% and more in the months ahead.

Nor do the rate hike fanatics spend much time analysing household spending which is remarkably weak and weakening, especially in per capita terms.

Rounding out the errors is the neglect of the inflation outlook. From now, July 2024, the weak economy and, importantly, the direct deflationary effects of the electricity and rent concessions from the federal and several state governments that lowered prices in these areas will crunch inflation lower, back to the RBA target, in fact.

There is also little appreciation for global developments, highlighting the myopic “analysis” behind the calls for yet higher Australian interest rates.

Interest rates around the world

As inflation cascades and economic growth continues to weaken globally, proactive central banks are cutting interest rates or have signalled they are on the cusp of a series of further monetary easings.

Interest rate cuts have already been delivered in the Eurozone, China, Canada, Sweden and Switzerland, plus several emerging market countries. In all cases, investors are “pricing in” more interest rate reductions in the coming months.

Investors are also reading the hard economic data to price in interest rate cuts in the U.S., the UK and New Zealand, among others, as weak growth and rising unemployment inevitably feed into an inflation outlook that is consistent with central banks in those countries hitting their targets in 2025.

While the RBA does not – and never will – move interest rates in lockstep with the other countries, the broad trends in the ups and downs in interest rates are as clear as they should be obvious.

Even in the last few years, when policy was eased during the COVID pandemic, the RBA moved rates in the same direction as all other comparable countries. When the post-pandemic inflation surge emerged, the RBA – belatedly, it must be noted – followed the interest rate hiking cycle around the world.

It is as plain as day.

It would be fanciful for the RBA to hike in the months ahead when most other countries are on track to cut interest rates by 100 to 200 basis points.

The inflation outlook

Whatever the June quarter inflation data show, the key issue is what happens from there. Credible forecasters know that inflation will, for the September quarter, drop to near zero. It will be that low because of the impact of weaker economic activity, a moderation in wage growth and the effects of policy decisions that will lower electricity prices and dwelling rents.

The economists at Westpac and CBA are among the good forecasters pointing to inflation returning to the target in the next 12 months.

The Treasury forecasts in the Budget had inflation within the target in both 2025 and 2026.

For those begging for an interest rate hike on the basis of the June quarter 2024 inflation data, there is also the strikingly obvious point that a rate hike in the months ahead will not impact the historical inflation data for the first half of 2024.

But any such hike will impact jobs, growth and inflation in the year ahead.

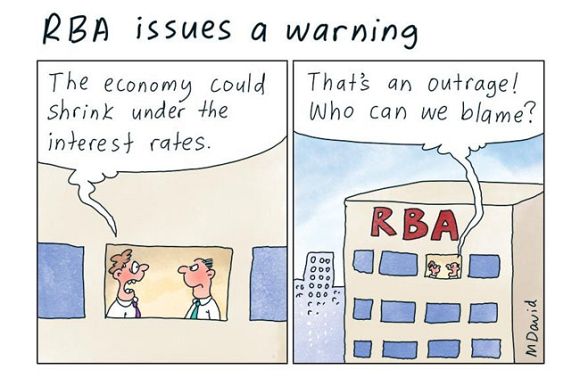

Consequences of an RBA error

If the RBA panders to the monetary masochists and hikes interest rates again, or indeed, leaves interest rates too high for too long, the already damaged Australian economy will be littered with even more business failures, impaired business activity and an unnecessary rise in the unemployment rate. Inflation will fall to a level below the RBA target.

It is well known that the RBA has made serious mistakes with its recent policy settings.

In the period from around 2016 to 2019, it failed to cut interest rates when inflation was persistently below target and the rest of the world was cutting rates.

In the aftermath of the COVID lockdowns and the surge in inflation, it was slow to hike interest rates. The then RBA Governor, Philip Lowe, infamously set out the case for interest rates to remain at 0.1% until 2024 because inflation would remain low and the market pricing for rate hikes was wrong.

Having already increased interest rates so aggressively, the RBA would be playing with fire in hiking again with the economy already in a per capita recession and unemployment rising.

To be sure, the RBA could make a mistake again, but let’s hope the new governor, Michele Bullock, and her impressive deputy, Andrew Hauser, have not only learnt from those errors but are looking at the outlook for the economy, not the past, when it sets interest rates in the months ahead.

Stephen Koukoulas is an IA columnist and one of Australia’s leading economic visionaries, past Chief Economist of Citibank and Senior Economic Advisor to the Prime Minister.

Related Articles

- Reserve Bank playing with fire — beware of the creeping recession

- Unemployment — the forgotten target of the RBA

- RBA's next interest rate move likely to be a cut

- When it comes to unemployment, the RBA has got it wrong

- Australia can afford to fix the damage done by interest rate hikes

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.