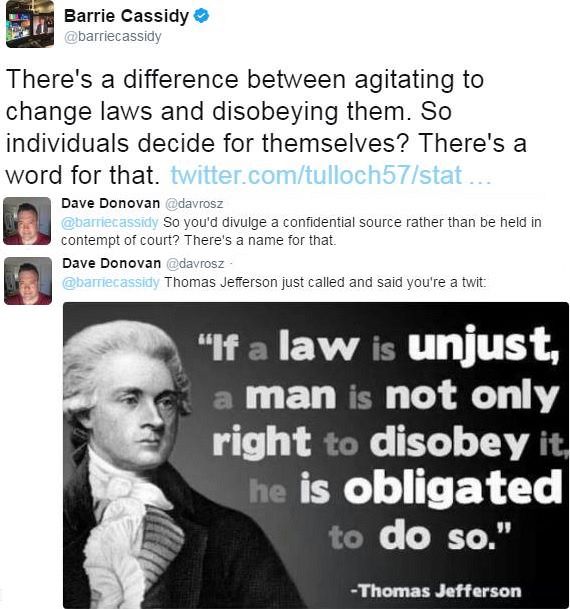

The response to Sally McManus' comments about breaking unjust laws reveals widespread mainstream media and public ignorance, writes law lecturer Ingrid Matthews.

WITH AN OUTBREAK of interest in and ignorance of two legal precepts, "rule of law" and the 1,500-year-old lex iniusta non est lex ("an unjust law is no law at all"), here is a bit of background on origins, authors, influences and adherents.

The bones of the debate are this: one of the highest placed union leaders in Australia (and IA contributor) Sally McManus, was asked by host Leigh Sales on ABC 7.30 on Wednesday night if she “believes” in the rule of law. McManus based her reply on the natural law philosophy that laws must have a moral dimension and a relationship to justice – and ought not cause injustices.

Over the years, philosophers have disagreed on the correct response to an unjust law and have attempted to codify types of injustice. Do we leave the state that makes unjust laws for a more just society that does not? Do we obey the unjust law for the sake of some greater social good, such as stable government? Is an unjust law nullified by its unjustness – is it neither valid nor authoritative – because it does not meet an essential criterion for being a law? Are we justified in disobeying this unjust command which is not a law? Are we morally obliged to resist the command that is not a law? Surely participating in and contributing to injustice is an objective moral wrong?

It will surprise nobody that these nuances were lost in the ensuing debate, which has (rightly) been overshadowed by the strategically brilliant and intelligently articulated reply from South Australian Premier Jay Weatherill to yet another poorly-conceived Federal government thought bubble on energy supply.

Well done @JayWeatherill for calling out the Liberals over the energy crisis they've created https://t.co/40ZeVYHSEt

— Wayne Swan (@SwannyQLD) March 16, 2017

Watch SA Premier @JayWeatherill shirtfront Federal Energy Minister @JoshFrydenberg on live TV, after gatecrashing the presser #auspol pic.twitter.com/82sMOqJl9j

— ABC News (@abcnews) March 16, 2017

But as I was writing a jurisprudence lecture on Aquinas and friends today, I decided to post this explainer on the debate and the origins of its underlying – and false – assumptions.

The incoherence of conservatism, then and now

Despite their fondness for identifying longevity with authority – the longer a principle has been around and survived, and been invoked through the ages, the greater legitimacy it carries – conservative thinkers set to work with predictable clickery and conformity.

Like most conservative incoherence, these are people who reject identity politics, yet judge a clear statement of principle not on what is said but who is saying it. So when McManus says that unjust laws can and should and will be challenged, your local conservative reporter frames her sentiment as imminent anarchy. This is despite the fact that McManus is drawing on an ancient (in European years) tradition found in the work of Augustine, Aquinas and Locke, works which provided the rationale for the American War of Independence, ideas which inspired Martin Luther King.

In contrast, when laws which do not suit the conservative agenda are challenged – such as the mining industry campaign against a perfectly sensible and just attempt to establish some kind of sovereign wealth mechanism – it is simply "reported" as though impartial and reasonable, and not an affront to principles of equality and justice.

Following the 7.30 interview, prominent voices and high traffic sites such as Buzzfeed, Fairfax and the ABC immediately started peddling the angle that challenging unjust laws is some kind of unprecedented call to arms. In fact, it was the top union leader in the country sensibly discussing workplace safety and the human cost of employer negligence that sees human beings killed on construction sites. (And shout out to Crikey, who lined up left of Buzzfeed and to Guardian journalist Paul Karp, who took on two Fairfax heavyweights.)

Workplace safety and union solidarity sit squarely within the remit of Sally McManus’ job description. A philosophy that rejects unjust laws also lies squarely within her expertise. But she does not get to enjoy the faux-neutral reportage – acceptance – that is enjoyed by the mining industry, for example, or the passing of profoundly anti-democratic laws by conservative governments — laws which are specifically designed to safeguard mining industry interests. These laws massively increased fines and maximum custodial sentences for protestors, while others dramatically reduced the maximum penalties for toxic spills, and other forms of destruction of country caused by big mining.

#auspol

— timjbo (@pleaseuseaussie) March 15, 2017

ACTU boss Sally McManus OK with workers breaking ‘unjust laws’

I wonder what Bill will say about this?https://t.co/UgXzo5V5N6 pic.twitter.com/wWaq2Gll4h

Conservative commentators could draw the most rudimentary – and relevant – comparisons between huge fines for striking unions and insultingly small penalties for employers who create conditions which kill workers. The edgy performative crew of political writers and editors could read a book – or Google – before tweeting out ahistoric ignorance (and Their hegemonic response relies on Hobbesian authoritarianism, which is coded into all Australian Constitutions. This tradition says the lead task of the political leadership is "peace, order and good government". While the U.S. chose Lockean revolutionalism to throw off English colonial rule, Australia chose Hobbesean order. We are not the loveable anti-authoritarian larrikins we like to think. We still have a foreign national as our head of state.

Both Hobbes (1588-1679) and Locke (1632-1704) were deeply influenced by the English Civil War, from which the version of liberal democracy practiced here sprang. This model relies on the doctrine of separation of powers for power-sharing arrangements across the executive, the parliament and the judiciary. The sovereignty of parliament – where sovereignty is the legitimate authority to pass laws governing a population in a defined territory – prevailed over the absolute monarchy that preceded it.

Theology and theory for population control by church and state

Social contract theory thus has its origins in a period of turmoil and bloodshed, of the people rising against tyranny. It was also an age of secularisation and the declining influence of the church as the lead source of moral authority. The theory proposes that citizens are born into a social contract with the state. The social contract replaced original sin as the prevailing belief system imposed on new born babies by the ruling class, the academy and the judiciary — none of whom ever gave birth to a baby.

If rule of law is closely associated with the social contract, original sin was a favourite fetish of Augustine of Hippo (354-430). The earliest coinage of lex iniusta non est lex is attributed to this famously sexually confused man of god — a man who rejected the pleas of Pelagians seeking refuge from the fall of Rome, because Pelagius rejected the Augustinian cult of baptism.

It is beyond me (and Pelagius) how anyone could hold a new-born baby and think ah yes, so sinful, best get a self-hating turned-celibate man to half-drown the wee one before she can grow into a professed Christian who refuses asylum to refugees fleeing imperial violence. Augustine thought it necessary to cleanse new-borns of the taint of the fall in the Garden of Eden, and this kooky nonsense prevailed over more sensible and obvious truths of the innocence, blessings and joys of a living breathing baby.

Reading on Pelagius. pic.twitter.com/VkUy7PlWfy

— ~Dedicated (~_^) (@PenetratedLobe) February 8, 2017

Aquinas (1225-1274) came along around 800 years later. He, too, made his name by theorising the norms imposed by a patriarchal and cruel Church on the most precious and demanding (and life-threatening) imperative of humankind — birthing new humans. In a common technique, Aquinas looked to the works of Augustine and re-interpreted that with which he did not agree.

He also Christianised the philosophy of Aristotle and retrospectively justified the rampant slaughter of Muslims that was the Crusades. For this immensely immoral rationalisation of the seemingly endless violence of the Christian west, Aquinas was canonised by Pope John XXII in 1323. His jurisprudence continues to be taught today as a reformist and enlightened force for good (an altogether different take is taught in my classes). His Summa Theologica is quite literally part of the Western canon.

Because the legacy of men who theorised our relationships with church and state is confused and deluded, the contemporary discourses which draw on this legacy also tend toward a confused babble of mostly conservative white blokes bickering over how best to govern (regulate/control) various sectors of the population.

There is nothing new under the sun, as my grandmother was fond of quoting from Ecclesiastes, which fittingly also gave us vanity of vanities, all is vanity! For the enthusiasm of some journalists to happily make themselves the story is not only an exercise in vanity, it is in breach of first principles of their own profession.

Rule of law — in the news and in real life

Speaking of first principles, "Do you believe in the Rule of Law?" is a question by and for simpletons, which does not (or should not) fit any description of the host or the guest. It is tacky gotcha journalism, it is joining the outrage machine, creating and participating in manufactured controversy. This is dismaying at best coming from the national broadcaster. It shows bad faith and displays zero intention for a nuanced and meaningful dialogue, which will educate rather than divide an already divided populace.

The interview was immediately and, I suspect, unspontaneously disseminated across social media by journalist colleagues with significant followings. These posts gave every impression of their authors being on notice to make an ABC programme the story. The technique is getting old: tried and tested at Q&A, it seems 7.30 and Insiders have boarded the clickbait bus, just in time to see (I hope) its traction in decline.

Bill Shorten's comments have muted the Twitter army that backed Sally McManus last night. Waking up to the risk of endorsing her. https://t.co/7yFtmb3xT2

— David Crowe (@CroweDM) March 15, 2017

Nah. https://t.co/lSHa5rINJy https://t.co/GVv3WzNILu

— Greg Jericho (@GrogsGamut) March 16, 2017

1. - 1856, Victorian stonemasons down their tools + march to Parliament House

— The AMWU (@theamwu) March 16, 2017

- Win 8 hour work day

- (illegal!)

-1938, Waterside Workers’ Federation members refuse to ship iron to Japan.

— The AMWU (@theamwu) March 16, 2017

- (illegal)

Meanwhile, the robust defence of rule of law from conservative quarters came with deep ignorance of its content, origins, meaning and status. If there is an upside to this embarrassing clamour, it is that someone, somewhere, will be invited to speak clearly on the biggest lie of common law legal systems. The claim that "all are equal before the law; and no-one is above the law" is not true and was never true. Maybe, just maybe, we will all learn about this in the wake of McManus’ comments.

The noble idea of equality before the law – symbolised by a blindfolded Lady Justice – is what lawyers call the content of the rule of law. It travels alongside its blue blood cousin, which describes democracy as a government of laws and not of men. Both principles perpetuate mythologies of objectivity, neutrality and impartiality to which conservatives earnestly subscribe. White justice tends to look impartial to white people, for example. Neither principle bears up under the most cursory, let alone critical, scrutiny.

Our gaol populations reveal the truth of a violent and racist patriarchal state; a government of propertied white men, for propertied men, by propertied white men. Our gaols are full of Aboriginal people, of poor people, of illiterate people, and people with intellectual disabilities and mental illness, people who are survivors of child sexual assault.

You will not find Rule of Law in the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (Imp), the authorising legal instrument for the creation of the federated nation. That is because Rule of Law is not a law. It is a foundational principle of the common law, and the common law is a product of the class-riddled imperial mind set of upper-class Englishmen.

These same people traversed the globe, slaughtering whole populations, claiming ownership of vast tracts of land, plundering the resources of territories which were sustainably managed for millennia. Backed by military force, they attacked the institutions and traditions of first peoples, of indigenous governance and learning, spirituality and law-making – and then told them everyone is equal before the law. All this was also backed by the soft power of theory and principle – of tropes and lies like Rule of Law – produced by the complacent and comfortable men of god and state, and the academy.

Their descendants and direct beneficiaries are a dominant minority who overwhelmingly constitute the executive (highest decision-making power and authority) of every institution in our society — private and public, government and political parties, corporations and industry, universities and religions, and the fourth estate. This lot are still out in force promulgating the lies and violence of yesteryear. Like their forefathers, they deploy positional privilege to belittle and oppress those who speak truth to power.

@davrosz @NewbyNewbys

— Stephen Clendinnen (@GargamelClen) March 16, 2017

What is abhorrent is people who break the law and use their position of power to avoid all consequences. pic.twitter.com/mT9TbOcxNL

This is not some social media storm in a teacup. Aboriginal people killed in custody and workers killed on construction sites are real people — in life and in death. And if there is one thing every culture treats seriously, it is the taking of the life of a fellow human being. But in our culture, not all humans are seen as fully human by the dominant group. It is they who ensure that when it comes to the errors and horrors of their own class, there is still nothing new under the sun.

Ingrid Matthews lectures in law at the University of Western Sydney. You can follow Ingrid on Twitter @iMusing or her blog Ecomuse.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

The response to Sally McManus' reasonable comments about breaking unjust laws reveals Australia to have the dumbest journos in the world.

— Dave Donovan (@davrosz) March 15, 2017

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Merle Thornton's illegal protest led to breaking the 30 year ban on married women keeping their public service jobs. #resistaus #ausunions pic.twitter.com/ENQV9wLQZt

— Nadine Flood (@NadineFloodCPSU) March 16, 2017

Solidarity. Subscribe to IA for just $5.