As misuse of communication technology rises, fact-based journalism to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda is under even more attack, writes Lee Duffield.

PUBLIC ADDRESSES late in 2021 by Maria Ressa – the Philippines journalist accepting the Nobel Peace Prize – and by Wanning Sun, a Sydney China scholar, displayed opposite experiences and understanding of the abrogation of media rights.

Maria Ressa is self-consciously the journalists’ journalist as she declared at Oslo, on 10 December:

"I stand before you, a representative of every journalist around the world who is forced to sacrifice so much to hold the line, to stay true to our values and mission: to bring you the truth and hold power to account."

Journalists’ journalists

Ressa was jointly sharing the Nobel award with Dmitry Muratov, the co-founder and editor of independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, whose citation was for defending freedom of speech in Russia over decades, with 'fact-based journalism... to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda'.

A founder of Rappler, a publication adamantly committed to human rights, Maria Ressa revisited the troubles inflicted on journalists across the board, with several killed and gaoled, under the presidency of Right-wing wild-man Rodrigo Duterte:

"The attacks against us in Rappler began five years ago when we demanded an end to impunity on two fronts: Duterte’s drug war and Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook."

"The more I was attacked for my journalism, the more resolute I became. I had first-hand evidence of abuse of power."

In her analysis, “an absence of law and democratic vision for the 21st century” has been enabled by a misuse of new communication technology:

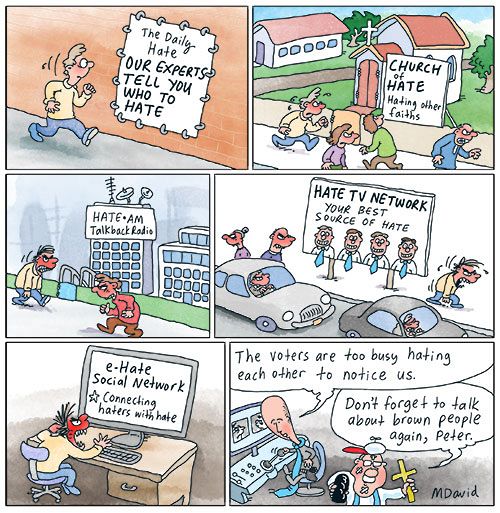

“... setting the stage for the rise of authoritarians and dictators around the world… toxic sludge coursing through our information ecosystem, prioritised by American internet companies that make more money by spreading that hate….”

How to respond?

According to Ressa:

"Well, that just means we have to work much harder."

Winning friends

The journalist, who remains herself under threat of imprisonment, on any old charge, thanked many people and organisations for their protective actions, like the Nobel committee, or the #HoldTheLine coalition of more than 80 groups defending media freedom across international borders.

Ultimately, she said, it came down to character, for journalists intending to do their job, to deploy moral power against any oppressor:

"The more I was attacked for my journalism, the more resolute I became. I had first-hand evidence of abuse of power. What was meant to intimidate me and Rappler only strengthened us."

Anti-media

Wanning Sun, self-described as a “media academic” and an explainer of cultural norms and official thinking going on in China, has had an easier row to hoe, until now.

She would today find her position in debate about China and media somewhat shattered by the change of government and radical change of policy since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012.

As a professor of media and communication, her guest presentation, online, of the Australian Centre of China in the World Annual Lecture at Australian National University (ANU) on 30 November, showed up the tensions.

In background, migrating to Australia from China in her youth, Wanning Sun studied in Sydney, moving eventually to the media studies department at University of Technology Sydney (UTS) – where sympathetic study of an at least nominally Marxist regime would be a comfortable fit – and made a career from translating and analysing Chinese language media, in Australia and abroad.

For a few decades of change, it would be fairly congenial. China’s industrialisation and entry into the world economy was generating new legitimacy, interest, cooperativeness and goodwill; there was scope even for work without sanction on such themes as cultural inequalities in China.

Like the ANU address itself, the academic work could be loosely wrapped in “post-modern” rhetoric, carried over from the 1970s and still pushed hard by any with an investment in it: a thicket of coded language, of tropes, "the dominant", the "other", "problematic" as a noun and the deployment of a tumble of words to "reveal" an "inherent racism" of white men running everything.

Usually, drawing on the cultural histories and fulminations on the nature of power by Michel Foucault, it says, more or less, that everything is text, culture is a mask for raw power, history has no use and, where the cult turns against journalism: a kind of Dadaism is proclaimed proscribing the concepts of fact and truth.

Wanning Sun sets up the idea of diverse media being actually a monolith and attacks the ABC and The Sydney Morning Herald, both represented as equally blameworthy with the bluntly reactionary News Corp press. This Australian "media" as a single entity, is accused of active complicity with state security organisations, to run pre-set government angles, whereby, through their construction of the China story, they have actually caused the bad state of relations between the two countries. The public are dupes, lacking agency; journalists are crooks.

From a fairly contorted facsimile of an argument, here are some of Sun's lines.

The security and intelligence establishment’s concern about the China threat is one thing. But establishing this threat in the public imagination requires the media to collaborate actively. The media also need to give the impression that their news stories are natural and logical rather than ideologically pre-determined, so readers believe that this is the only story worth telling, and there’s only one way of framing it.

To decry poor China, we journalists may deploy “the artful use of headlines” and “cherry-picking of facts”, or “can try using disclaimers”, or “try creating an eerie atmosphere, spooky music, dark silhouettes, fingers typing urgently on a keyboard, and a cinematic mise-en-scene befitting a John le Carré novel”.

But how about some facts that have made many Australians distrustful?

Military blocking of the China Sea sea lanes in disregard of international tribunals; armed forces build-up on a clear trajectory to mobilisation; explicit declaration of intention to invade Taiwan; blatant and proclaimed crushing of democratic government, free media and rule of law in Hong Kong, in violation of the 1997 agreement on “two systems one country” — and continued repression in Tibet and of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang province.

The days of the trade explosion we now see in a rose-coloured hue. China’s admission to the World Trade Organization ushered in an optimistic time, no matter if even at the start the rules were not well kept; not much idea of acting in a rules-based order where you were supposed to refrain from coercion to have it all your own way.

The new aggression has been seized on by antagonists of China, like the Liberal Senator Eric Abetz, objected to by Wanning Sun for putting some of her Chinese Australian colleagues on the spot, at a Parliamentary inquiry. He demanded to know: would they condemn outright the way the Beijing Government has been heading?

That was clearly a bit rough. On one hand, it potentially exposed them to punishment by the regime. On the other hand, it exposed them to accusations of running a "fifth column" here in Australia. What to do if caught in the cross-fire?

Returning to Maria Ressa of the Philippines, to offer us a lead.

Being a leader among journalists, she would see the workings of media and the world in pragmatic and ungarnished terms: it is time for some honest analysis of what is bothering this Chinese leadership and what they might do; decide if the particular reporting task is worth its risks; if so be guided and driven by getting to the truth of it, establishing the facts, and know that a good story sells itself, can provide its own defences, and while things can get dangerous, can earn you friends, and respect.

Dr Lee Duffield is a former ABC foreign correspondent, political journalist and academic.

Related Articles

- COVID-19 shows how journalistic class is failing us

- Queensland Election: Youth crime and race get politicised in Townsville

- There is hope for the end of Australia's apathy

- News Corp's closing of newspapers a blow to Australian communities

- Australia's Right-wing stranglehold over public interest journalism

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.