Compounded by COVID-19, the press has been unable to capture the tone of the nation due to a disparity of lived experience within journalism, writes Joel Jenkins.

SINCE FEDERATION, the working-class journalist has never been far away from the story of Australia, until now.

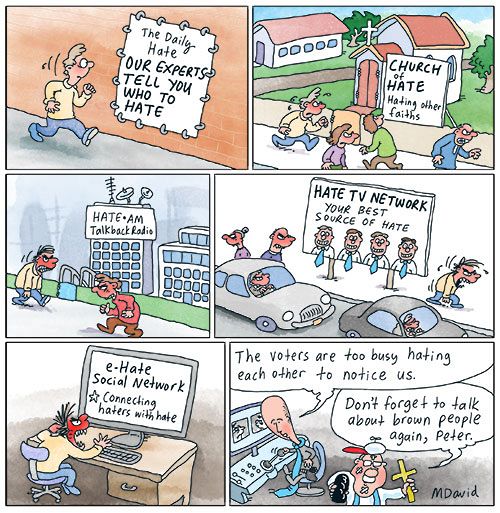

Behind the paywalls and punditry of today’s media there is a clear lack in diversity of viewpoints, not just internally, but externally as well. There have been discussions around the concentration of media power in this country but less about the concentration of ideas propagated by the press. Operating in the small turning circles of political influence (political favour) and job security, the press has joined the political class at the expense of an understanding of the issues of class that challenge our society.

COVID-19 has highlighted the lack of voices in the media that reflects the wider Australian community and the issues that matter to them — a process that has come from the elitism that has pervaded journalism, alienating sections of the community. This is evident from the raft of national contributors that have been unable to accurately capture the tone of the nation, whilst being unable or unwilling to corral the Government and Opposition to make decisions that reflect good outcomes for voting Australians.

I grew up down the road from Bob Hawke’s office in Coburg, also spending many days at my nan and pop’s house in Glenroy. My mum and her four brothers and sisters grew up there, well-priced housing commission clinker bricks, big families in every home.

One of mum’s friends who grew up down the road became a journalist for ABC in the early '80s. Although he came from one of the poorest families in the street, there he was, a Glenroy boy, helping to shape the national dialogue with his breadth of lived experience, bringing valuable insight to his tradecraft. Everyone loved him, including my anti-intellectual pop. He would come over – back in the '90s – and tell us about Myanmarese politician Aung San Suu Kyi and Bosnia.

In the Anglosphere, the shift towards middle-class university graduates within journalism has become apparent, gradually and no longer to be ignored, like the $12.99 Lebanese cucumbers at Woolies. The days of cadetships and copy room kids have been replaced by university-educated graduates equipped with family contacts in the industry, small and incestuous, with many favours still owing.

These valuable positions are now intersected with favour and influence via familiar LinkedIn networks and backyard tennis competitions. A cacophony of well-insulated, well-bred aristocrats tapping away with their indoor plants and French Bulldogs, positing on the very inadequacies they helped create, unknowingly drifting away from the pulse of the nation with the floating Canberra bubble they choose to moor their schooners upon. Sons and daughters of a managerial elite entering the industry via a conveyor of privilege and influence, instantly compartmentalised from most of the population and bereft of the social experience to qualify the educated observations they wish to make.

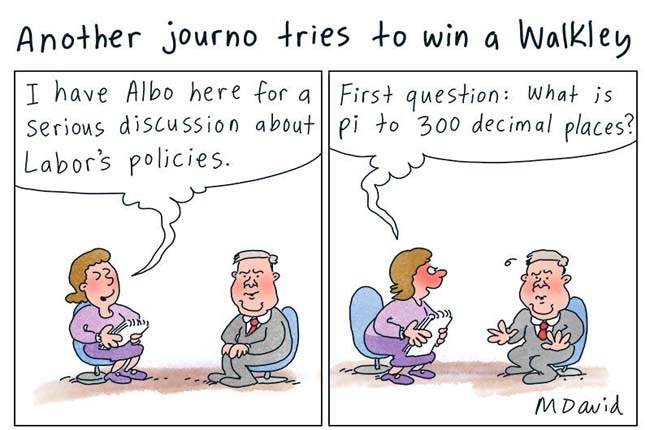

This article was initially a response to a Twitter beef (myself the belligerent) with Mr Dr Peter Van Onselen over his article in The Australian entitled: 'Covid reveals how our political class is failing us'. He mentioned in the comments that people shouldn’t bother if they haven’t read the article — I thought it was a hard task to get someone to pay to read an article, in a publication that didn’t generally consider them.

In his article, which I read, he speaks to the absence of pragmatism, leadership and good ideas in politics — yet he does so from a platform that has ensured this volatile environment. When he envisions the crumbling 'pillars of stability that once ensured Western democracy', he does so from the same marbled arches that Nero’s "Dorothy Dixer" viewed a burning Rome.

These duopolies and triopolies of Australia and the media platforms have entire interests that are counterintuitive and further removed from the average Australian. The incongruous nature of Van Onselen's position is that it betrays a lack of experience around issues that motivate the people of the country and an inability to acknowledge the impact of this on his perception and analysis. This is true throughout journalism in Australia.

When something as fundamental as the Fourth Estate chooses to switch its narratives based on a combination of independent political, ideological and economic interests, it can hurt the brains of a lot of people — especially those that sit outside what is deemed to be a genuine audience both politically and commercially, especially in a pandemic.

One picture of strength and unity, another an image of a 'state of disaster' — one side community and camaraderie, the other a Sword of Damocles, poised to render Victorians under 'shock and awe' restrictions. When bipolar messaging is applied according to political and societal delineations, it comes at the expense of a harmonious population and cogent national imperatives.

A healthy and diverse press environment could hold the Government to account for its lack of leadership, whilst looking to avoid national division over genuine responses to the "black swan" event of our lifetime — not well-off pundits like Peter Van Onselen channelling the plagues of ancient Rome and the lamentations of the Caesars.

There are a lot of people who can’t work from home, who cry in the supermarkets over the price of Lebanese cucumbers — their lamentations are the ones that should matter. With the possibility recent Morrison failures could be fatal, there are signs that the Murdoch alliance and its mythological "protector" status of the Liberal National Party are starting to show signs of fatigue.

It may look to enter its most uncanny form — salvaging its relationship with the Australian Labor Party. This about-face is a rare occurrence in the somewhat cyclical nature of the Murdoch apparatus, not seen since Kevin Rudd made the necessary arrangements in '07, not something that fits the narrative. It might be worth watching this space.

With the declining presence of working-class journalists and their unique social contributions, sons and daughters of managerial elites do not have the socio-cultural reference points they need to make balanced observations of our society, nor the counterweight from colleagues who can provide it.

A blindsided journalism has been unable to capture the disenfranchisement of broad sections of the population and the dire state of our democracy due to the failures of the political class. The nation would benefit from a more diverse media representation across class barriers, encouraging, more importantly, a more diverse representation across class barriers in Canberra.

The lack of economic, cultural and ideological diversity in journalists has overseen a rise in political corruption, scandal in this country’s politics, bad faith in the population and the reticence to meaningfully address it.

The challenges of COVID-19 have illuminated the societal issues that rise from careless and inconsistent messaging, the responsibility of those who deliver it and the lack of voices to represent the vast number of Australians under duress.

This comes at the expense of our democracy and everything we need to achieve as a common people, at a time that needs national imperatives to meet existential challenges with climate change and COVID-19. The lethargic and uninspired leadership in this country combined with the complicit press apparatus that perpetuates it is the centre of decay and rancour that has permeated the political class in Australia.

The lack of working-class voices in Australian media is no secret these days. An article by comedian and author Nelly Thomas laments the loss of this important social component and the balance and insight it can bring to privileged journalists in the media.

This loss is clearly observed now in the transmigration of journalists within the concentrated media landscape, as former Murdoch’s go to ABC and former ABC’s go to Nine-Fairfax, the working class get squeezed out, the ideas are extruded based on methods learned from a Murdoch tenure or a Channel 10 graduate program, no longer through working-class cadetships and valid lived experience.

Joel Jenkins is a writer and actuator. You can read more from Joel on Bogan Intelligentsia and follow him on Twitter @boganintel.

Related Articles

- Queensland Election: Youth crime and race get politicised in Townsville

- There is hope for the end of Australia's apathy

- News Corp's closing of newspapers a blow to Australian communities

- Australia's Right-wing stranglehold over public interest journalism

- A stand for journalistic freedom: Facing the digital avalanche in mass communication

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.