While many Indigenous figures support the proposed Voice to Parliament, there are still some who oppose it, but the mainstream media won't tell you why, writes Tom Tanuki.

MANY OF LAST WEEK’S Invasion Day protests made their resistance to a Voice to Parliament – a referendum for an Indigenous legislative advisory body, with no veto powers, to consult on laws that affect Indigenous people – very apparent.

This forced the Australian mainstream to acknowledge what it had tried hard theretofore to ignore: that Indigenous resistance to the Voice is more complex than Senator Jacinta Price objecting for the usual Right-wing reasons or Senator Lidia Thorpe objecting because she’s a “hate preacher” (to quote Andrew Bolt) or “stubborn”.

Afterwards, responses to an Indigenous-led “No” case and the attendant media coverage shifted from a fixation on Lidia Thorpe’s flawed personality to collectively dismissing “rusted-on” activists. The co-chair of the peak body making the case for the Voice has dismissed Invasion Day rallies as a “noisy few”. A metric ton of opinion pieces has been unleashed in the pages of The Guardian and The Age from progressive voices responding to this anti-Voice perspective.

Some of them are thoughtful, like Marcus Stewart’s article. Some of them are less so, like Waleed Aly’s article, which opts for hand-wringing over how rude and stubborn political discourse is these days. Big commentators are lining up for a go.

What stuns me is that amid a deluge of centre-Left thought pieces attacking the Indigenous-led, anti-Voice case, they still refuse to publish what that case actually is.

Despite the calls becoming impossible to ignore, or to blame solely on Thorpe, they’re still not explaining it. This is inexplicable.

I devoted a video to this subject earlier in thelast week because I thought these perspectives were being stifled. I thought Invasion Day might help them get clarified in the mainstream, but it hasn’t. Ever the optimist, I thought I might try again in writing. I am not desperate to insert myself as a White layperson into this debate. I want to point to prominent arguments or concerns from Indigenous thinkers about the Voice campaign because if you read the Australian mainstream media, you still wouldn’t know they exist.

Here goes.

The brilliant Amy McQuire penned an article on a history of opposition to constitutional amendment plans. I recommend you read it now. She outlines the history of racist provisions in the Australian Constitution, the beginning of efforts to deconstruct them with the 1967 referendum and inadequate protections against anti-Indigenous discrimination currently offered by the Racial Discrimination Act (which racists can override when it suits them, like former PM John Howard did when he launched a military campaign against Indigenous people in the Northern Territory).

After establishing a need for improvement on Indigenous rights as set out in our Constitution, Amy then demonstrates how actual efforts to do this have crumbled through confusion and compromise.

Many people who understand the Voice to Parliament as a “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity to achieve reform may not be aware there have been two “once-in-a-lifetime” iterations of it before. One was You, Me, Unity, a non-specific campaign to promote constitutional recognition. It was launched while a panel on constitutional recognition tasked by former PM Julia Gillard was developing its findings.

That campaign was abruptly replaced by Recognise in 2012 after the panel’s findings were issued. They recommended resolving historic racist provisions in our Constitution and compensating with other remediating disadvantage-combating provisions. Instead, we got Recognise, which was birthed as a multi-million-dollar campaign to promote the idea of constitutional recognition. It was launched before concrete proposals had even been finalised. (Ring any bells?)

This vagueness began to alienate Indigenous people, who had questions about the expensive process. Criticisms included that it did not appear to offer anything tangible to Indigenous people, opting instead for compromise-driven “gesture politics” focused on appealing to a largely White, settler voter base. (Many more objections to Recognise can be found in this excellent Indigenous Law Bulletin retrospective.)

Despite all the money thrown at the campaign, Indigenous community opposition to it increased and, after several years, Recognition was shuttered. This, despite the insistence by the Recognise campaign that 87% of Indigenous people supported it. (Ring any bells?)

Writing in 2015 for The Guardian about that misrepresentation, Arrernte writer and activist Celeste Liddle said:

‘In the vast wilderness that is “the media”, it never ceases to amaze me just how much Indigenous opinion gets moulded and curtailed in order to promote a mainstream agenda.’

She could have written that today.

Subsequent efforts to reassemble a campaign for constitutional recognition included a 2017 First Nations summit organised by the Referendum Council. This involved a series of nationwide First Nations delegate meetings, followed by a national summit that would ultimately draft the Uluru Statement which informs the Voice campaign. A group of sovereignty-minded Indigenous delegates walked out of that meeting. hey included Lidia Thorpe and Wiradjuri elder Aunty Jenny Munro.

She said at the time:

“We need to protect and preserve our sovereignty. We demand a sovereign treaty with an independent sovereign treaty commission and appropriate funds allocated. We don’t need a referendum. We need a sovereign treaty.”

The Uluru Statement outlines ‘Voice, Treaty, Truth’, which is basically a suggested order in which its proposed measures are to be tackled. Sovereignty-minded Indigenous activists, writers and thinkers disagree, demanding that treaty take priority. Treaties are nothing new, nor anything extraordinary. New Zealand, Canada, the U.S. and many other countries all negotiated treaties with Indigenous peoples.

Wiradjuri and Badu Island activist and educator Lynda-June Coe, discussing the debate around constitutional reform, wrote:

‘...Indigenous nations who have signed historical treaties have maintained the structural qualities of nationhood in their contemporary political survival against the state. The structures that I refer to for instance are political autonomy, tribal governance of treaty lands and reservations in what are deemed “domestic dependent nations”.’

Treaty is a very tangible demand because treaties have tangible outcomes.

Some have argued that through considerable state-based organisational efforts, treaty negotiations are forging ahead anyway. But Indigenous communities are still entitled to question the efficacy of advisory bodies which are at risk of being undermined and defunded, like so many before. They are entitled to question what real-world benefits gestures like a Voice to Parliament can actually bring about for Indigenous communities.

Gomeroi activist and Tent Embassy caretaker Gwenda Stanley asked Q&A panellists last year about this, questioning the Voice while asking what real-world effect native title had brought about. Many native title claims, as she rightly pointed out, are bogged down by impossibly lengthy bureaucratic and legal battles.

Amy McQuire positions the conflicted position of people with questions over the Voice:

‘Our last national representative body – the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples – was hindered from the very beginning by a lack of funding from Labor. It was always vulnerable and eventually died. I would never vote against the idea of another Black representative body but I wonder, if it is to happen, how we use it to fight the ongoing fight?’

After a demonstrable history of gestures that are offered to Indigenous people but not followed up by significant real-world reform, only to be later thrown back in their faces as evidence that they will “never be happy”, can we blame Indigenous suspicions at how much good the next gesture will do?

Gary Foley spoke with great clarity at Invasion Day about a long history of Indigenous activist demands for self-determination and Aboriginal sovereignty. Compared to that, he said, current calls to give Indigenous people yet another advisory body (after a history of Indigenous advisory bodies being appointed, then defunded) look like no more than “lipstick on a pig”.

These are valid arguments, whether you agree or not. Plenty of other Indigenous figures have made them — I have only listed a few. They are easily accessible; even a layperson like me could find them! It is astounding that these ideas are not being platformed even while they are being constantly attacked from above.

I can only conclude that mainstream Australian discourse is committed to stifling the expression of Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination politics as a valid perspective. We must all push back against that.

Tom Tanuki is a writer, satirist and anti-fascist activist. Tom does weekly videos on YouTube commenting on the Australian political fringe. You can follow Tom on Twitter @tom_tanuki.

Related Articles

- Getting good and vocal about a Voice to Parliament

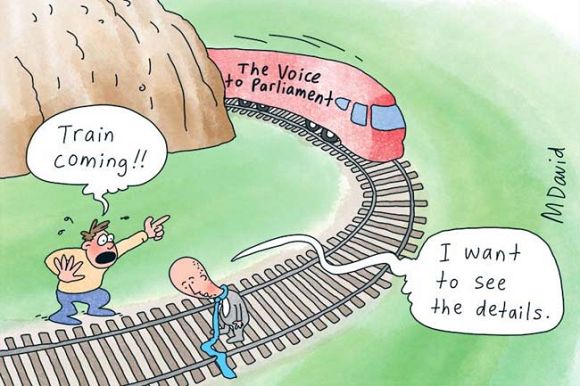

- Voice referendum: The devil is in the lack of detail

- Indigenous Voice to Parliament a good step, but not far enough

- Albanese's Voice to Parliament referendum should be a no-brainer

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.