Shutting down discussion on the Israeli embassy shooting can't be our only response — otherwise, talking about violence becomes no different to promoting it, writes Tom Tanuki.

A FRIEND AND COMRADE sent me the Israeli embassy shooter’s manifesto, published by Ken Klippenstein. They thought I’d find it worthwhile reading.

I baulked a bit, partly because I have sat through so much far-right manifesto drivel for my work that I have become desensitised to any sense of intrigue over these political screeds written as cross-promotion for someone’s act of violence. (I hear some of these losers are using AI to write their manifestos for them lately. Can’t even be bothered to write out their own final political will and testament.)

But read it I did. I found it a very compelling bit of writing.

Using violence to make a political statement

Klippenstein introduced the manifesto, written by Elias Rodriguez, who shot and killed two people outside the Israeli embassy on 21 May this year:

'I am publishing it here not to glorify the violence – which I find abhorrent and condemn – but so the public can better understand the truth of what happened.'

I hesitate instinctively to pen any kind of honest reflection on a manifesto like this, or for that matter, to ask for it to be published. There are good reasons for my hesitation, which I will consider here.

One reason is because I believe in the power of non-violent activism. I’m not discrediting armed resistance; rather, I don’t like to associate my politics with individual acts of violence.

I don’t think it’s a model by which my politics will be advanced, or a better world I envision realised. Like Klippenstein, I abhor the violence; not just the act, but the notion that these acts might be how we prosecute our politics to our neighbours, on our own doorsteps. I’m not thrilled at the prospect of fetching the popcorn while we all watch an American Anni di piombo unfold, either. I don’t think that would do us, or the people of Gaza, any good.

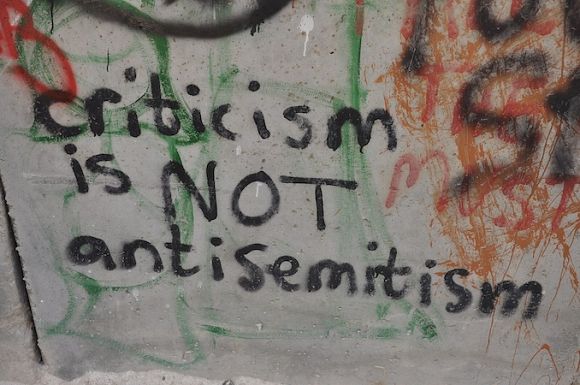

It's evident there is an appetite for discussing this shooting and the manifesto online. The response in the public arena is a knee-jerk kind of repression, as though discussing it is indistinguishable from zealously promoting it.

The world’s biggest political streamer, Hasan Piker, received a ban from streaming platform Twitch merely for reflecting on this massive, international news item. The Australian and other assorted media outlets have been targeting political influencers like Clementine Ford and Grace Tame for their commentary on the shooting, which respectively consisted of calling for a refocus on the thousands of dying Gaza civilians and rejecting the Zionist claim that the shooting was "antisemitic".

The act was brutal and violent, but it’s okay to say the shooter wasn’t antisemitic when there’s no evidence for that. Nor is the manifesto, for that matter. It tries to weigh the scale of the devastation and slaughter on occupied Palestine, before then considering the importance of acts like their own, which they describe as "armed demonstration".

The manifesto states:

A word about the morality of armed demonstration. Those of us against the genocide take satisfaction in arguing that the perpetrators and abettors have forfeited their humanity. I sympathise with this viewpoint and understand its value in soothing the psyche, which cannot bear to accept the atrocities it witnesses, even mediated through the screen.

But inhumanity has long since shown itself to be shockingly common, mundane, prosaically human. …I am glad that today at least there are many Americans for which [my] action will be highly legible and, in some funny way, the only sane thing to do.

Countering terrorism by countering points of view

On to my other reason for hesitating. In the securitised post-9/11 world of counter-terrorism we all inhabit, the first thought we might encounter when reflecting on work like this in public is: don’t say anything too close to what they tell you a terrorist might say, because you may be prosecuted under counter-terrorist laws. "They", meaning the state and its counter-terrorism surveillance apparatus.

As Kneecap can tell you, when your trade is in changing minds over the urgency of solidarity with Palestinians against the Israeli genocidaires, it’s important to be cautious about your words. Our Zionist political opponents are very talented at using the counter-terrorism apparatus to shut down political opposition to Israel’s brutality, and one of the most effective ways they do it is by using Hamas’ status as a proscribed terrorist organisation. I have seen Muslim comrades in the days of the patriot movement, and Australia’s associated heady Islamophobia and eager counter-terrorism, be disappeared for a spell simply for a wrong word on social media here or there.

There are some anti-Zionists who insist on nothing short of explicit, public support of that proscribed terrorist organisation, and this is a subject of endless debate. I would like to think there’s a kind of dialectical synthesis somewhere in that debate. Perhaps something like: don’t sell out the notion of Palestinian armed resistance, but also, be strategic and don’t go to jail for nothing. I think we have to factor mounting state repression into our strategy.

In that climate of repression – not just from the well-oiled counter-terrorism apparatus but in the rapid clamping down of all pro-Palestinian demonstrations after 7 October, 2023 – a political doublespeak is becoming popularised.

Luigi Mangione has become a folk hero and if you’re an adult in public with a (Nintendo) Luigi hat on, everyone knows what you mean.

One of the most popular memes in America after U.S. President Donald Trump’s election is simply saying: “Somebody needs to do it”. Everyone, instantly, knows what "it" is; crucially, they also know why nobody can say what "it" is in public.

American internet and political commentator Taylor Lorenz, covering the 'Somebody needs to do it’ meme, argues that the jarring gear shift away from pandemic-era health and welfare priorities contributes to this appetite for political violence. People saw the state value their lives, and then rapidly, brutally cease to do so. We’re possessed of a fundamental bleakness about the world we’re saddled with; the world we’re dumping into the lap of young people.

Banning political words creates room for political acts

I’m the child of Armenian genocide survivors who were outraged ever since Israel’s inception with the temerity to wave about a Holocaust as a foundational excuse for an invasion and campaign of colonialism and displacement. Later, when Israel supported Turkey’s denialism over the Armenian genocide, my grandfather became an anti-Zionist, and then my father, and then me. I was further politicised by reading the works of Noam Chomsky at a young age. That was my framework for understanding international geopolitics: a very bleak one.

Young people now don’t have to learn about manufacturing consent from Noam Chomsky books. In real time, they have to watch Western states, counter-terrorism apparatuses and stenographer media outlets frenziedly furnish the grounds for the further annihilation of Palestine, and criminalise anyone condemning it too loudly — even as we all peer behind the curtain and see the slaughter happening daily on our mobile phones. It is maddening.

The manifesto begins:

“In the wake of an act, people look for a text to fix its meaning, so here's an attempt.”

Then it essentially accuses the rest of us, in our outcry over the inhumanity of Zionists, of doing little but soothing our own consciences for all the good it’s done.

I don’t necessarily agree. And I don’t think that’s a good enough case to then start killing people. But like the abovementioned dialectical synthesis, I have to ask: even if I don’t wholly agree, there’s something in it, right? More than speaking to my own sense of guilt, there’s something in it.

It might be my bleakness speaking. We have been corralled into feeling this way by the repression of anti-genocide sentiment and the forward march of the genocide regardless of how vigorously we all decry it.

It was America’s own John F Kennedy who once said:

“Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

Are you allowed to quote the genocidaires’ own icons at them?

No, I don’t want to live in a world where brutal murders become the du jour method for people to prosecute our politics to the masses. But every day for over 600 days, we have watched (what will eventually be counted as) hundreds of thousands of slaughters. Those slaughters have happened in aid of advancing the case for Israeli land and ethno-supremacy.

That is the express political point of denying the right of Palestinians to live freely, or at all. Every civilian death in Gaza, every bombed hospital and starved Palestinian child, is about prosecuting ethnostatism. That is the violence of the embassy shooter, writ large, enacted by a state of overwhelming brutality, daily, for years. So I already do live in that world.

This is the world you’ve left for your young people. You’ve criminalised their ability to condemn it freely. You shouldn’t have to wonder why they, as a result, are developing an appetite for contemplating assassinations and murders.

You may stem the tide now by doing everything you can to seek a political solution to end the genocide immediately.

Tom Tanuki is an IA columnist, a writer, satirist and anti-fascist activist whose weekly videos commenting on the Australian political fringe appear on YouTube. You can follow him on Twitter/X @tom_tanuki.