The republic proposal must include substantive protections for the disadvantaged, writes Dr Robert Wood.

WHEN WE TALK about the republic, we are talking about constitutional change that is structural. We are talking about changing the laws to better reflect who we are and what we would like from our government.

The critical task is to build a sense of self-governance into it, a type of autonomy and sovereignty.

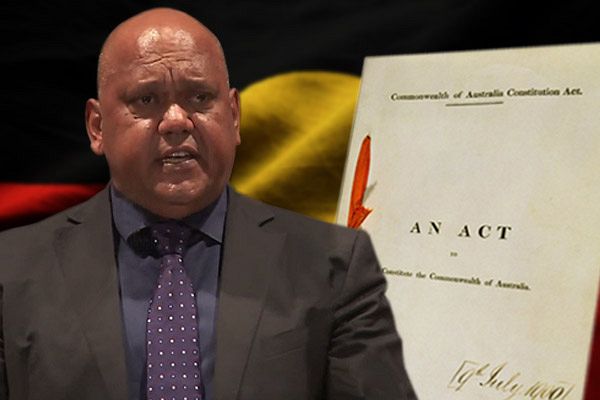

Aboriginal activists have led the way when it comes to thinking through this last phrase. It should not be immediately assumed that this is in conflict with the nation in its potential; the republic must be Indigenised as well. This is about undoing the colonial basis of the state, about rectifying the fundamental violence that came with invasion, about making things right by listening properly to people that are here and whose land it always was and always will be.

In writing that, I acknowledge that I cannot do this and so there is a point when one must become silent. It is important not to take up too much space when asserting one’s citizen activism and making room for those who are better equipped to articulate their rightful position on this continent.

My republicanism is mainly grounded in a critique of whiteness and not only what can be accomplished when abolishing the British Crown’s presence; and so, it is responsive to the failures of republicanism as it has been constructed at present.

The desire is to be truly intersectional and that means thinking through needs not only identity.

And so, in that way, and thinking of myself as a Malayali, what kind of constitution would we like to see? How can it become for all the people with Aboriginal people in the lead? Those questions matter most of all when we think of the Voice to Parliament, treaty, and, of course, our head of state.

They matter too when we think about how our daily lives can improve, because, after all, surely that is the aim of a good constitution — the founding document of good government. It needs to be said then, that when they come around to designing it, we must put our most vulnerable at the top of the agenda.

That is why we need to think of a "bill of needs".

Needs are above and beyond rights. Yet, the state is failing to provide them. People can see the philosopher Raymond Geuss for more academic work on this, but common sense would bear it out. To look only at hunger, not to mention housing and all the other basics, we can turn to the work of Food Bank.

Its website states:

The Foodbank Hunger Report 2019 revealed that one in five Australians have experienced food insecurity at some point in the last 12 months. This means that for 21 per cent of Australia’s population, there has been at least one time in the last year when they didn’t have enough food for themselves or their family and could not afford to buy more food. It’s hard to believe this is happening in the "lucky country", where we produce enough food for 60 million people.

With food, it is a question of distribution, which is supported by theorists like Amartya Sen, who wrote about the Bengal famine under British occupation.

Food is a need and yet our access to it is not constitutionally enshrined. This is most acute too, in remote communities, which people can read about here. If Australia cannot even guarantee a meal for many of its citizens, what hope do we have of looking after our own people in a way that is meaningful?

Related Articles

- An Australian republic must be founded on a non-violent society

- Another Queen’s Birthday — isn’t it time to break free?

- Don’t let the Kiwis beat us to an Australian republic

Rights are the bedrock of liberalism and we recognise them in our contemporary public discourse, given its roots in the nineteenth century. But we need to move beyond them to comprehend what has happened since, just like we need to move beyond class if we are to make sense of identity politics.

This matters for informing a new constitution that can adequately respond to the desires of people on this continent.

In that way, a bill of needs stating what is reasonable would lay out clearly what everyone can expect. We should not take food security, housing, the environment, or anything else for granted. We cannot assume government will do that. That we do already speaks of the privilege of our representatives rather than their empathy and ability to recognise that many people are doing it tough. What this means is a continuation of middle-class welfare because it plays well with the public, but that is only a selfish easygoing nationalism that forgets those who are being left behind on a daily basis.

A bill of needs might be one way to rectify it, or, if not that, then a dialogue about why we need to do everything in our power to feed the hungry, clothe the poor and provide a welcome home to those who are being left out by our callous bipartisan politics.

Dr Robert Wood is chair of PEN Perth. A Malayali with East Indian Ocean connections, he lives on Noongar Country in Western Australia. The author of four books, Robert has held fellowships at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.