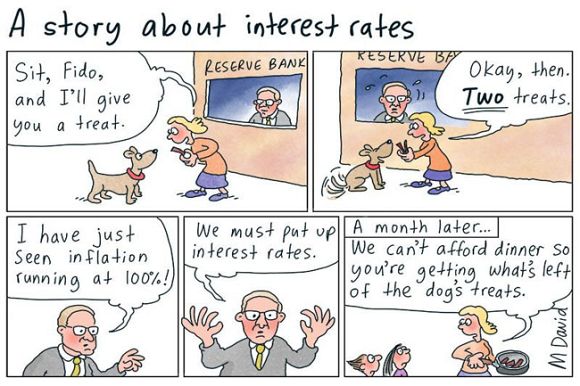

The Reserve Bank of Australia has repeatedly raised interest rates to counter inflation while ignoring massive profits from big business. And so, those who can least afford it keep getting hit. Dr Evan Jones reports.

THE (NATIONAL) economy at the macroeconomic level is treated by central bankers and most academics as a thing in itself. Its essence is characterised by aggregate indicators — gross domestic product, aggregate unemployment rate, inflation rate, etcetera.

Macroeconomic fetishism

Inside the macroeconomy is a black box. Analysis of the "microeconomy" is monopolised by the paradigm of Neoclassical Economics, enthroned in the (English language) economics "discipline" since the late Nineteenth Century.

Neoclassical Economics is not rooted in the empirics of economic structures but in a priorism. It is a fairy story. The black box of macroeconomic theory is facilitated by the absence of an adequate microeconomic (structural) analysis.

The much-revered J M Keynes played a part in this unfortunate scenario. In confronting Britain’s 1930s Depression (with large-scale ongoing unemployment), Keynes’ stylised analysis was purely at the macroeconomic level with inattention to empirical detail.

This was even at the time that Britain’s relation to the global economy was changing and its internal economic structure undergoing significant transformation. Within that analytical constraint, Keynes highlighted that mass unemployment could be sustained, that a dearth of aggregate demand was the source and that decisive public action was necessary to counter that dearth. And fair enough as a short-term fix.

But after Keynes’ premature death at 62 in 1946 came the "Keynesians".

After 1945, countries committed themselves to economic reconstruction. Some (Britain and Australia) even committed themselves formally to the pursuit of "full employment".

Annual budgets were deemed as offering more flexibility, complemented by monetary instruments, towards this end. Thus was conceived "macroeconomic (or demand) management". "Fine-tuning" was the new name of the game. The private sector would do its usual (uncoordinated) thing and governments would step in, on the margin, to fine-tune the aggregate economy that delivered not merely economic growth but relative economic stability in the process.

The micro/macro divide was implicitly treated as a "market/policy" divide. The tertiary economics syllabus was duly structured with a microeconomics (Neoclassical Economics) and macroeconomics bifurcation in the core.

This delineation turned an analytical misunderstanding and convenience into a structured miseducation. Both in the academic analytical and policy domains, it led to what I called, 30 years ago, a "macroeconomic fetishism".

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Governor John G Phillips (1968-75), in a 1971 address, ‘Developments in Monetary Theory and Policies’, made this bald claim:

"The usual procedure is to set the policy dials in a way that we hope will produce reasonable balance between aggregate demand and supply."

Here is the black box in a nutshell. Phillips admitted that the authorities faced much uncertainty in the understanding of linkages and processes – a humility now disappeared within the RBA – but an unblemished and unwarranted optimism still prevailed that the task was achievable and purely at the macroeconomic level.

The macroeconomic fetishists never confront (or very rarely) that every policy instrument seen as purely macroeconomic has discriminatory structural impacts. It should be self-evident for budgetary and taxation measures (most of the specific measures being focused, but crudely labelled by the fetishists as "fiscal policy").

Any monetary policy instrument also has discriminatory structural impacts, as noted earlier with housing mortgages.

Ironically, in the 1971 address by "Jock" Phillips, the RBA governor belatedly slips in a part-page acknowledgement of "sectoral impacts of policy".

Claimed Phillips:

However, from time to time, it is suggested that policy should take account of developments in specific sectors of the economy and on occasions, general policies have been modified to take account of the needs of specific industries. For example, in 1969/70, special measures were taken to assist the rural and housing sectors and to shelter them at least to some degree from the generally restraining policy in force.

The current culture of the RBA’s macro fetishists has blotted out the previous official acknowledgement and the stark reality (self-evident to the layperson) of the sectoral impact of monetary policy instruments.

Ironically, in a 2004 publication (noted earlier), Phillip Lowe writes more like his predecessor Jock Phillips than his current self. There, Lowe admits to the uncertainties that accompany the inflation-fighting task. He notes the over-confidence of policy-makers in the 1960s who were then blind-sided by the "Great Inflation" of the early 1970s.

Lowe acknowledges:

'… success [in dampening inflation after 1990] can breed overconfidence and banish doubt, sowing the seeds of its own destruction… Guarding against the risks of falling into a similar trap in the future calls for a healthy spirit of self-doubt and vigilance, a willingness to question and expose to rigorous scrutiny well-honed convictions.'

Compare this manifest humility with Lowe’s current pigheadedness.

Lowe should have looked further back. Immediately following 1945, transition to a peace-time economy and reconstruction required big-picture thinking and open minds. There was no macro/micro bifurcation – on the contrary – structural and macroeconomic factors were inextricably intertwined.

I have laboriously outlined the post-1945 policy ambitions in Australia when war-hardened bureaucrats struggled – knowingly, if not successfully – with multiple demands. By the mid-1960s, however – and with a dominant Treasury Department now stuffed with economics graduates for whom World War II was ancient history – the academy and the economics/finance bureaucracy had settled into an artificial macro/micro bifurcation.

Thus was the character of the post-War boom period re-written by those living through it but skating on its surface.

Canadian-American economist J K Galbraith once (cited in political scientist Colin Crouch's State and Economy in Contemporary Capitalism) quipped – no doubt tongue in cheek as a war-hardened bureaucrat himself – that:

'Keynes had a solution without a revolution. Our pleasant world could remain: the unemployment and suffering would go. It seemed a miracle.'

The unprecedented years of the "long boom" seemed to confirm the analysis and its embedded optimism. There was a catch, however.

Sources of economic dynamism ignored

The sources of Post-World War II economic development are to be found in arenas other than macroeconomic "fine-tuning" addressed to aggregate statistics.

The long boom was predominantly a product of national government-initiated developmental projects (for Australia, think public housing schemes; the Snowy Mountains scheme; the initiation and support of a domestic auto industry; government-sponsored exploration and support for a mineral resources sector; the game-changing 1957 trade treaty with Japan, etcetera). These are precisely the things (and their background) neglected in economics textbooks.

Underpinning national governmental activities globally was Pax Americana, which fostered a "military Keynesianism" and with the Western hegemonic U.S. tolerating national developmental practices according to their own cultures contrary to the "free market" (not least West Germany and Japan, and later South Korea) as supplementary vehicles in the Cold War against the USSR and its satellites.

The whole was enhanced by cheap oil, courtesy of the exploitation of oil-producing countries. Macroeconomic management was icing on the cake at best. (For Australia, see my 1989 working paper ‘Was the Post-War Boom Keynesian?’.)

These important empirical and institutional details have been treated perennially imperfectly in syllabus options or not at all (not least with the disappearance of economic history courses). One other glaring absence is the joint stock limited liability corporation.

The corporation and market power

The corporation, a not irrelevant entity in the modern economy, is given short shrift in the economics syllabus. It is non-existent in the core. Matters of the corporate sector’s market power are treated on the margin or not at all.

Confronting "restrictive trade practices" only gained legislative legs in Australia with the Trade Practices Act 1974 and the creation of the Trade Practices Commission (TPC) by the Whitlam Government in 1974 — subsequently, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) from 1996.

There is a history of repeated failures, partly wilful, to offset the growth and abuse of market power. The Fraser Government –John Howard, the Minister presiding at the time – soon neutered the Act. Some positive changes were belatedly made to the Act, but administrative will was often lacking.

The market power of retail giants Coles and Woolworths, for example, was facilitated by endless green lights given to takeovers by each of these companies. Ditto the green lights to substantial concentration in the banking sector.

Worse, the Howard Government installed investment banker Graeme Samuel as ACCC Chairman (2003-2011), specifically to neuter the ACCC’s effectiveness — a successful ploy.

In turn, market power and its abuse have been legitimised by the courts. A key judgement is ACCC v Berbatis Holdings, HCA, 2003.

Berbatis is not a corporation but a minor landlord in a shopping centre. Nevertheless, the judgment led by Murray Gleeson AC GBS KC (previously a corporate lawyer) and three conservative accomplices (William Gummow AC, Kenneth Hayne AC KC and Ian Callinan AC KC) is breathtaking in its insouciance and implications.

Gleeson opined that the stronger party to a commercial relationship has not merely the right but the duty to exploit to the greatest extent the weaker party (here, a tenant under family duress).

Thus, has corporate market power grown over the decades. Private market power has been considerably enhanced by the privatisation of public utilities and government business enterprises.

Some market power is, of course, inevitable where technology demands it and in a relatively small national economy. But corporate market power in Australia (and its associated political power) has been greatly enhanced during the last 50 years with a competition regulator in place with more promise than substance.

This elephant in the room remains invisible to our central bankers while being bleeding obvious to the general public.

There were two periods in which governments (Labor both times) attempted to confront market power and its associated pricing power head-on.

First, the Whitlam Government established the Prices Justification Tribunal (PJT) in August 1973. Reliance on the PJT was a default strategy after the failed referendum to acquire Federal Constitutional power for price control.

It soon ran into a headwind. I remember the crunch came when steel monopoly BHP warned that if the PJT was going to interfere in its pricing decisions, it would simply cease to invest. Blackmail. The wounded PJT immediately went into obscurity with the Fraser Government in office (John Howard, a relevant minister) and was quietly disbanded in June 1981.

The second occasion was the establishment of the Prices Surveillance Authority (PSA) in 1983. The PSA was part of the much-publicised Prices and Incomes Accord between the government and the unions. If the unions were going to restrain wage demands, they wanted a quid pro quo with business price rises — thus the PSA.

The PSA had a tripartite structure, with a PSA executive presiding over meetings with representatives from the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and the Business Council of Australia (BCA).

A sometime PSA employee has told me that “… companies were questioned openly [with] quite intrusive powers of data collection from companies [from which the PSA] issued lengthy reports”. This practice would be inconceivable today.

A PSA staffer friend notes that the effectiveness of the PSA was hampered by the presence of Federal Treasury staff who seemed to be clueless about the real world. But there was a more fundamental issue.

My PSA friend highlighted the difficulties of the task:

It was always a problem establishing whether, say, a high market share was due to predatory pricing or superior performance and marketing. What is a reasonable rate of return? How should you treat inter-company loans and inter-company payments for, say, intellectual property? What is a fair price for these? A really big issue was what level of marketing expenditure is excessive — how much of a firm's surplus should be spent on advertising and how much should just go into lower prices?

Corporate profit is the driving force of the capitalist system: and the intrinsic drive for the acquisition of market power that delivers pricing discretion, super profits and relative organisational stability – but also deep socio-economic distortion – is its loose cannon. Government attempts to offset this inexorable drive, starting with the U.S. Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890), have impeded the beast only on the margins.

However, it is essential to explicitly acknowledge the nature of the beast and to work towards offsetting such power, even on the margins. The RBA wilfully ignores the evidence of corporate pricing power and its origins, looking for convenient scapegoats to tackle its "god-given" mandate of a 2-3 per cent inflation rate on average over a short time period.

The RBA’s wilful neglect was facilitated by the closure of the PSA in November 1995, its remnants being incorporated into the newly formed ACCC. Offsetting corporate pricing power has since then not been a high priority of the ACCC.

Recently, I received a letter from AGL Energy Ltd noting that it is increasing my electricity rates by a mega percentage (AGL had previously notified us of a mega percentage rise in our gas utilisation rates). AGL pays us effectively nothing for our solar generation feed-in.

On the same day, I read an article titled ‘AGL flags huge profit lift as power prices roar back’.

AGL was evidently trying to claw back significant losses from the previous year – due heavily to the crazy functioning of the national electricity market – to date tolerated by relevant regulators and authorities.

Some June letter writers to The Sydney Morning Herald (SMH) were equally indignant. Regardless, are the prices of significant utility services on the RBA’s radar? And if AGL price hikes are also a vehicle to finance the huge cost of moving to renewable energy, the RBA’s cash rate hikes are not going to reduce the energy price hikes’ contribution to inflation.

Looking through a glass darkly

What is the RBA, fronted by Lowe’s self-righteous discourses, really up to?

Another June letter to SMH, under the sub-title ‘RBA taking sides?’, cuts to the chase:

'With the RBA continually raising interest rates to rein in inflation, blaming wages instead of the ludicrously huge profits big business is making… can we just call it what it is: class warfare?'

That letter sums it up.

Lowe’s term of office expires this September. Even SMH has editorialised that it’s time for him to go. Implementation of the recommendations of the Government’s March 2023 report, 'Review of the Reserve Bank of Australia', demands a new head to oversee desired change.

Any notion that necessary change is going happen requires a degree of optimism not cognisant of the socialisation of the RBA’s 1,300 workforces nor of the entrenched imperatives of the tight-knit global class of central bankers.

On 4 July, the RBA held the cash rate steady. Lowe and his flock haven’t learnt anything new. He is still incanting the catechism of a "soft landing". More likely, he fears losing his $1 million job and going into the history books as a heartless boffin employed beyond his capacities.

Read part one of this story here: Reserve Bank has gone mad

Read part two of this story here: Reserve Bank ignorant to truth behind Australia's inflation

Dr Evan Jones is a political economist and former academic.

Related Articles

- Reserve Bank ignorant to truth behind Australia's inflation

- Reserve Bank has gone mad

- Reserve Bank forsaking Australians' best interests

- RBA review dashes hopes for reform

- No meaningful reform from review of RBA

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.