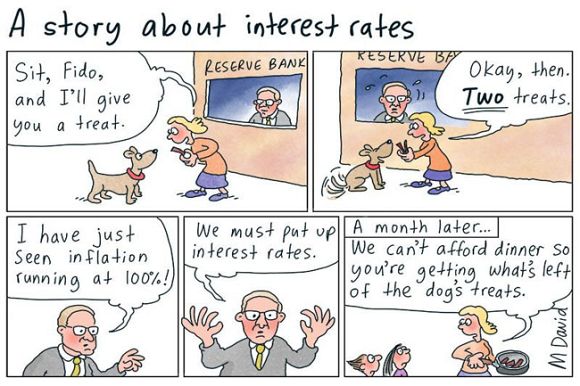

The successive rises in the cash rate to March 2023 by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) leave one doubting the intelligence of its Governor, Philip Lowe, and his senior staff.

*Also listen to the audio version of this article on Spotify HERE.

The further rise in the cash rate to 3.85% on 2 May 2023 confirms one’s doubts.

The cash rate began its most recent descent in November 2011, lowered from 4.75% to 4.50%. The rate was pushed down successively to 0.10% in November 2020, where it stayed until May 2022. In March 2021, Lowe claimed that the cash rate would stay low for another three years to 2024. The rate was then raised during ten successive months to 3.60% in March 2023. Many would-be mortgagors apparently took Lowe at this word.

Philip Lowe speaks like an automaton, delivering the conventional wisdom in myriad re-phrasings but which remain opaque. Yet Lowe is “earning” over $1 million a year (the U.S. Fed’s Jerome Powell’s salary is around US$200,000 (AU$295,842)). His deputies are on a good earner as well. Salaries are supposedly set to acquire and reward expertise.

Moreover, the formal reason for affording central banks independence is that the detached expertise of central bankers must be given free rein for analysis and implementation without the interference of ill-informed and opportunistic politicians. But where is the expertise?

The RBA employs over 1,300 staff, a huge total and growing over the last decade. Why are so many formally well-educated brains not filtering intelligence to the peak of the pyramid?

Lowe has a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the very top economics departments in the English-speaking world. Lowe is technically savvy but, evidently, the capacity for lateral thinking was not part of MIT’s curriculum. However, mainstream economists continue to give unequivocal support to Lowe’s actions and pronouncements.

Inadequate attention has been paid to the damage caused by the rock bottom cash rate of 0.10%, held at that level for 18 months. The intelligence of the move was not questioned at the time (other central banks were doing the same). It fostered a dangerous rise in home mortgage lending to people desperately (and not unreasonably) trying to make the leap into home ownership. It also fostered a flight from bank deposits of older people escaping negative returns on their hard-won savings, many into the arms of racketeers.

It took a belated questioning by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) general manager Agustin Carstens in April 2023 (even then a marginal comment) to reach the local media. However, Carstens remains thoroughly orthodox in his thinking that it was faulty application rather than the instrument itself that is the problem.

An RBA spokesperson claimed they felt that (in dropping the cash rate) they had to act strongly to offset the effects of the COVID lockdown. But what is the implied mechanism to stimulate general demand and growth? They don’t have one. Are businesses going to be borrowing more if prospects remain dim?

The housing market central

I don’t believe that the near-zero cash rate was a significant trigger for the current Australian inflation in general. Rather, it is the impact on the housing market that matters. A 2002 academic paper by Shuyun Li et al notes that, by 2017, housing loans constituted more than 60% of total private sector credit in bank credit portfolios. And that extraordinary figure pre-dates the near-zero rate era.

With finance sector deregulation during the 1980s, it was decided that the liberated finance sector could be controlled purely by the imposition of prudential controls, in the form of prescribed equity capital to asset ratios. Everything else could be left to the price mechanism, with quantitative controls ditched.

The prudential regime itself was later tweaked to give various asset classes a differentiated risk weight. Thus did housing get a lower risk weight than business lending, because mortgages are always secured by physical assets. Which in turn provides an incentive to push more housing lending by contrast with business lending.

Add the phenomenon of mortgage securitisation. The RBA is fully supportive of this phenomenon, with senior representatives appearing regularly at the securitisation industry’s November conferences. The RBA sees securitisation as a vehicle for enhanced competition and scale in the provision of housing loans, as the smaller banks and non-bank lenders use securitisation proportionately more than do the major banks.

Yet the RBA has no concern for the scale of securitisation, nor for whether the securitisation option influences the attitudes and practices of loan managers, nor for the question of who ultimately owns securitised mortgages — of major concern for mortgagors threatened with default and repossession. It’s a home mortgage sausage machine, without restraint.

The RBA has tweaked prudential requirements on home loans slightly over time, but this is a marginal change. The near-zero cash rate regime, securitisation and the escalation of interest-only home loans for home-owners as well as investors (which also doesn’t bother the RBA, even though it dilutes loan repayment capacity) has resulted in households in the mortgage belt being now in a precarious position, living hand-to-mouth to avoid default.

The RBA does acknowledge mortgage stress; this from its media release of 7 February 2023:

‘Some households have substantial savings buffers, but others are experiencing a painful squeeze on their budgets due to higher interest rates and the increase in the cost of living. Household balance sheets are also being affected by the decline in housing prices.’

Yet the RBA and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (split off from the RBA in 1998) don’t care about stressed mortgagor. Rather, they care only about the potential impact of impaired mortgage loans on the lenders’ balance sheets.

Cash rate hikes are themselves inflationary

Bizarrely, one important source of inflationary pressure comes from the RBA itself. Cash rate hikes feed directly into home mortgagor rates. House investors, a group with pricing power (not least in a very tight rental market), push up rents which contribute further to inflation, enhancing accommodation stress as well.

There is no explicit acknowledgement that housing is a special sector. There should be upfront coordination with the Federal Government with respect to significant migration levels and the automatic impact on housing demand. Moreover, housing is location-bound (space doesn’t figure in the economics curriculum), the stock slow to increase (in spite of governments catering to spiv developers), with prices linked to the credit quantum.

Lowe co-authored a paper in 2004 following his residency at the central bankers’ BIS. Its title is ‘Securing sustainable price stability: should credit come back from the wilderness’. Central bankers are now inclined to see credit control as a defunct indicator from pre-deregulation days.

Lowe here (in the context of unmediated asset prices inflation) says credit levels are potentially dangerous, we need to keep our eye on it but we’re not going to do anything about it. When Lowe pushed the cash rate down to 0.10 % in November 2020, he had forgotten the concerns of his younger self.

That cash rate hikes might themselves be inflationary has received little expert or media attention. The highly respected Joseph Stiglitz claimed such causality in December 2022 when he noted that interest rate hikes deter targeted real investments that would alleviate supply shortages and thus contribute to ameliorating inflationary pressure in the medium term.

Soft landings and other priestly incantations

The RBA treats the economy as a black box, something that can be manipulated hydraulically up and down in size, with the aim of achieving a preferred “balance” of unemployment and inflation rates. The hope is that squeezing the black box at just the right level will result in a “soft landing”.

The RBA February 2023 media release claims:

‘The Board is seeking to return inflation to the 2-3 per cent range while keeping the economy on an even keel, but the path to achieving a soft landing remains a narrow one.’

This is just so much poppycock.

The RBA acknowledged in February 2023 that:

‘The Board recognises that monetary policy operates with a lag and that the full effect of the cumulative increase in interest rates is yet to be felt in mortgage payments.’

Yet it raised the cash rate again in May 2023 without waiting for the lag to operate. So much for a soft landing.

A “soft landing” is part of the incantations arising out of a latter-day variant of witchcraft. And why the 2-3% range as a means to salvation? The RBA first described the 2-3% regime as a good outcome, subsequently a goal, and now a target. The then RBA Governor Bernie Fraser (1989-1996) arbitrarily determined the range, considered “generous” at the time by comparison with New Zealand’s Reserve Bank Governor Don Brash’s harsh regime.

Lowe’s RBA shamelessly raised the rate again to 4.10% on 6 June. In his speech to the Morgan Stanley Summit the day after, there is again little thought to the lagged “full effect”.

Lowe repeats the mantra regarding being in search of a “soft landing”, if more hesitant and oblique:

“[Our] path is one where inflation returns to target within a reasonable timeframe, while the economy continues to grow and we hold on to as many of the gains in the labour market as we can. It is still possible to navigate this path and our ambition is to do so. But it is a narrow path and likely to be a bumpy one, with risks on both sides.”

Another of the incantations concerns “inflationary expectations”. This is an evil spirit that must be exorcised from the black box. Inflationary expectations are always treated in the abstract and everybody is afflicted with them. All being afflicted, everybody is guilty of fuelling inflation. Except they aren’t.

Canadian economist Jim Stanford’s 2002 report to the Canadian Labour Congress on Canada’s central banking policy and the economy, in a rare exposé, notes:

But the assumption that expectations will determine the future course of inflation is wrong. And the resulting policy conclusion – namely, that wages must be suppressed below inflation to prevent higher expectations being “locked in” – is both unjustified and deeply unfair. Every Canadian may have certain expectations of future inflation, but their ability to protect themselves accordingly varies greatly depending on their place in the economic and social pecking order.

The group that does have the ability to materialise inflationary expectations are corporations with market power.

Here’s a quote from the horse’s mouth (reported in the New York Times, 31 May 2023, behind a paywall, but reproduced here):

‘PepsiCo has become a prime example of how large corporations have countered increased costs, and then some. Hugh Johnston, the company's chief financial officer, said in February that PepsiCo had raised its prices by enough to buffer further cost pressures in 2023.’

Such corporations with market power are precisely the potential sources of inflation that are taboo territory.

Lowe’s Morgan Stanley address hones in on inflationary expectations:

“...if people expect inflation to stay high, then it is likely to stay high. Firms will adjust their pricing behaviour and workers will seek bigger pay increases to compensate them for the higher inflation.”

“Firms will adjust their pricing behaviour”? This phrase is slipped in without follow-up. The RBA declines to recognise corporate pricing power, but instead, it concentrates on unions. The RBA claims to be monitoring union inflationary expectations via a survey of union officials. Yet it’s my understanding that union demands are perennially centred on catching up with existing rises in living costs.

This is why the RBA’s “inflationary expectations” mantra remains in the domain of witchcraft.

Read part two of this story here: Reserve Bank ignorant to truth behind Australia's inflation

Read part three of this story here: RBA's heavy-duty rate rises a lethal tactic in class warfare

*This article is also available on audio here:

Dr Evan Jones is a political economist and former academic.

Related Articles

- Reserve Bank forsaking Australians' best interests

- RBA review dashes hopes for reform

- No meaningful reform from review of RBA

- Reserve Bank not to blame for rising interest rates

- Reserve Bank renovation well overdue

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.