As Mathias Cormann leaves Australia’s Senate after seven years as Finance Minister, Alan Austin reviews his contribution.

FINANCE MINISTER Mathias Cormann may have a better shot at the top job with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) if they don’t read his resumé. The Minister leaves Parliament at the end of October and has applied to become Secretary-General of the Paris-based club of the rich, developed liberal democracies.

Of all finance ministers of the 37 member nations, Senator Cormann almost certainly has the worst record. That’s based on several measurable outcomes.

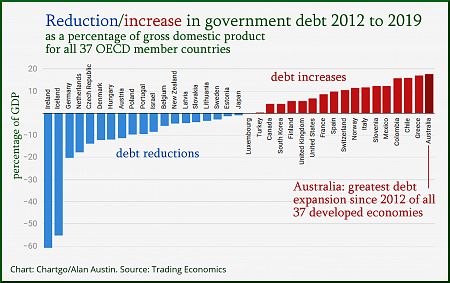

Gross debt added worst in the OECD

At the end of 2012, Labor’s last full year in office, Australia’s state and federal gross debt came to 27.5% of gross domestic product (GDP). Of the 37 OECD members, including Columbia which joined this year, that ranked a creditable fifth lowest. Only New Zealand, Chile, Estonia and tiny Luxembourg had less debt.

Since then, most well-managed economies have reduced substantially the debt stacked on during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Ireland and Iceland both repaid more than half. Germany, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and Denmark all reduced theirs by more than 12% of GDP. Seventeen OECD members increased their debt over that period, most by small percentages of GDP. Only four nations increased their debt by more than 15%. Australia was the worst with a 17.6% blow-out. See chart below (data from tradingeconomics.com.)

As of last Friday, more than two-thirds of all gross debt Australian governments have added since 1854 has been added while Cormann was Finance Minister. He added more debt in the last five-and-a-half months than Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard did in five years and nine months during the GFC. From a very modest $271.7 billion when he took on the job, it has soared to $820.3 billion.

Budget deficits among the losers

Through the six boom years from 2014 to 2019, Australia did not produce a single budget surplus. Germany, Norway and Luxembourg delivered six, New Zealand, Sweden and Switzerland achieved five and five countries delivered four — Denmark, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Greece. Yes, Greece. Of the 37 OECD members, fewer than half generated no surplus in that period. Australia is in that loser half.

Net worth

The clearest indicator of the failure of the Coalition to manage the nation’s finances is net worth, shown in the monthly Finance Department reports (Table 1, Page 1).

Net worth measures government assets minus liabilities. Assets include cash, land, buildings, investments, infrastructure and heritage and cultural assets. Liabilities include government borrowings, debts to suppliers, superannuation and other debts.

During the two years in which former Prime Minister Tony Abbott with Cormann as Finance Minister tried unsuccessfully to manage the economy, Australia’s net worth plummeted by a staggering $114.6 billion down to negative $320.6 billion — the lowest level ever to that point.

It collapsed further through the Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison terms to fresh all-time lows, reaching negative $568.3 billion in February this year before the pandemic struck.

The lowest this ever reached in the BC era – before Cormann – was negative $263.8 billion. That was in September 2012 towards the end of the GFC. It recovered over the next 11 months to negative $205.9 billion at the time of the 2013 Election and, according to the 2013 PEFO, was set to continue its climb back to positive values.

Mitigating factors for Mathias

There are few, if any. The economy inherited by the Coalition in 2013 was the world’s best-performed. Australia in 2013 had the highest median wealth per adult and the best record for infrastructure development. Productivity was in an 18-month streak and hours worked per adult were at historic highs. The jobless rate was 5.7%, which was in the OECD’s top eight. Economic growth was among the leaders, interest rates were at an optimum 2.5% and the Aussie dollar was close to parity with the U.S. dollar and at near-record highs against other currencies. Economic freedom, according to Heritage Foundation, was the highest in the OECD.

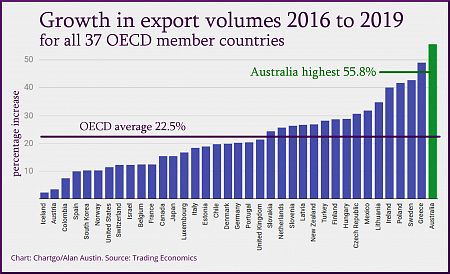

Conditions throughout Cormann’s tenure as Finance Minister have been the best since the post-war boom. Australia enjoyed a phenomenal surge in corporate profits and the strongest exports growth of all OECD economies between 2016 and 2019. See chart, below.

So, no excuses. There may even be aggravating issues beyond his portfolio, as IA colleagues have reported here, here and here.

This is not to suggest Australia having the worst finances of all developed economies over the last six years is Cormann’s fault alone. The decisions which led to these dismal outcomes – on spending, investment, trade, tax rates and tax collections – are Cabinet decisions. The Cabinet is, of course, advised by BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue, Woodside and Rupert Murdoch.

Ex-ministers off overseas

If Cormann lands in Paris, he will join several former ministerial colleagues who left to work for foreign entities. These include Andrew Robb (China), Christopher Pyne (Ernst and Young), Julie Bishop (Palladium and Greensill), Jamie Briggs (PricewaterhouseCoopers) and Ian Macfarlane (Queensland Resources Council which serves Adani, Glencore, Rio Tinto, Itochu and other foreign companies). Even the unemployable Tony Abbott now works for the British Government for free.

At least Monsieur Cormann, if such is his future, is not working for a foreign corporation he aided during his tenure. That is something.

Alan Austin’s defamation matter is nearly over. You can read an update HERE and help out by contributing to the crowd-funding campaign HERE. Alan Austin is an Independent Australia columnist and freelance journalist. You can follow him on Twitter @AlanAustin001.

Related Articles

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.