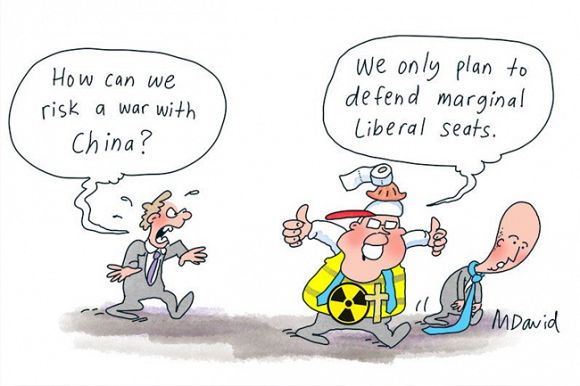

As tensions between the U.S. and China grow, Australia's nuclear submarine program has become less to do with our defence and more about placating the American Government, writes Dr Lee Duffield.

DEFENCE INDUSTRY MINISTER Melissa Price, on 9 November, declared the country’s nuclear-powered submarines would be built in South Australia.

How would this be done? Constructing the ships around imported reactors? It added into the brewing of questions and arguments since the sudden announcement of the nuclear plan and immediate cancellation of the French contract for conventional submarines on 16 September.

Trying to make sense of it all, several analysts, mostly through the Lowy Institute publication, The Interpreter, and at think-tanks to the Left and Right, have produced these main points:

- that American policy towards China is the main factor in this mix;

- that Australian sovereignty stands to be diminished, even if its security might be helped; and

- that the insult to France and its consequences, while not the main game, remains important — especially as it affects the standing of the Australian Government.

Sam Roggeveen, Director of the Lowy Institute’s International Security Program, contributed two articles, seeing the China-USA contest as the heart of it, with Australia now brought in more as a great power client, less as itself.

Roggeveen wrote:

‘The defence deal is a clear escalation and indication that Washington views Beijing as an adversary. It also has thrust Australia into a central role in America’s rivalry with China.’

U.S. reacts — Australia goes, too

The deal in question is the full package of the new tripartite defence arrangement, AUKUS (Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States), with Australia obtaining probably eight nuclear submarines at the centre of it.

As Roggeveen explains:

‘...the scale of this agreement and the close strategic and operational links it implies will create expectations from Washington. Australia cannot have this capability while assuming that it does not come with heightened expectations that Australia will take America’s side in any dispute with China.’

And as for the process, involving a sudden announcement to the Australian public:

‘It is extraordinary that this momentous decision could be made without parliamentary or public scrutiny.’

Allan Behm, Director of International and Security Affairs at the Australia Institute, gave a similar reading, seeing the decision to build long-range nuclear submarines for Australia as an American game, little to do with the defence of Australia:

The aim is to make possible an Australian contribution to U.S. battle plans against China which that country will view as profoundly threatening with implications also for war planning by Russia, North Korea and other nuclear-armed states.

Even leaving aside the fiscal profligacy and defence opportunity costs for Australia of the literal blank cheque issued by the Morrison Government, the nuclear submarine decision takes Australia into the heart of naval warfighting in East Asia and Southeast Asia.

“Step up to the bully”

Some steps to the right of Behm at the Australia Institute is Rowan Callick writing for the Centre for Independent Studies, a neoliberal and anti-communist lobby, in the current debate articulating much of the confrontationist thinking on how to deal with Beijing.

He has worked on the main point, that the Chinese Government has changed its policy, putting pressure on the West to respond to, a radical remaking of a globally ambitious Peoples Republic of China under President Xi Jinping — which is ‘the single factor that has given birth to AUKUS’.

He cited published statements from the Chinese President such as warning adversaries who might threaten China that they would “have their heads bashed bloody against the Great Wall of Steel”.

From the same source, the CIS, Tom Tugendhat has published a concise statement of the “step up to the bully” rationale for supporting initiatives such as the AUKUS deal. As the argument goes, China is building up enormous strength, its government, communist, wants maximum power at home and abroad, so there is an imperative to resist it both in economics and trade, and in military alignments.

Two strands of thinking

Ian Hill, in The Interpreter, puts together the two strands of thinking: (a) The United States wants Australia more tightly tied-in and (b) more recent, more aggressive Chinese policy will add to the pressure on Australian governments and the public to go along with that.

For the U.S., AUKUS is a win. It exemplifies the importance Washington attaches to deepening cooperation with key allies and strengthening their military capabilities to assist in deterring the security challenges posed by China in the region.

A very hard and costly undertaking

Great difficulty running a nuclear submarine program is foreshadowed for a country with no nuclear industry, where the navy for several years was unable to provide specialist crews for each of its Collins class submarines — rotating them ship-to-ship as vessels took turns in maintenance. There is also the long lead time proposed for getting the nuclear boats into service, starting with 18 months reserved for more discussion, for official thinking to get clarified on such questions.

Oriana Skylar Mastro and Zack Cooper have talked about many critics already raising ‘valid concerns’:

Critics of AUKUS... worry that 18 months is a long time to wait for clarity on the plan, and 18 years would be too long to wait for submarines. Nuclear-powered submarines will prove difficult and expensive for Australia to master and could create non-proliferation concerns. Washington, Canberra and London will have to mend ties with Paris as well as concerned friends in Southeast Asia, especially Jakarta. Others have argued that the deal ties Australia too closely to the United States or creates unnecessary tensions with China (although we would dispute these last two assertions).

The fracture with France

An American game it may be, but within Australia, the arguments have not subsided about relations with France, the scrapped ship-building deal at $90 billion having been important to both partners and a centrepiece of trust and co-operation in their joint security role in the South Pacific region.

Features and events in this debate:

Awkward body language for the Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, somewhat ignored at the Rome G20 meeting, then COP26 on climate change. Bringing an Australian Government video operator into the mingle, he did not exactly force the French President, Emmanuel Macron, to shake hands, “bushfires” style. But clearly the bloke did not approve, famously telling journalists, after, that Morrison had lied to him about the submarines deal.

Australian ministers fumbled around, seeking to apply some spin: the French would be “disappointed” but would get over it and still be friends. The message from Paris was actually that the French, after all a major power, had no sense they might be so patronised and were in fact livid, reacting with contempt and might engage in some retaliation at the ongoing trade talks between Australia and the European Union.

In the vanguard of concerns about the French connection, Richard Ogier saw further risks to Australia’s options as a sovereign state, and considered that:

‘In Europe, and not only in France, the image of Australia has suffered a direct hit. Australia may be a staunch U.S. ally, but under certain circumstances, was prepared to go beyond the old ANZUS alliance. Australians may be warm and welcoming, is the message sent, but watch for the kick when your back is turned.’

A full version of this article has been published in subtropic.com.au.

Dr Lee Duffield is a former ABC foreign correspondent, political journalist and academic.

Related Articles

- The risky business behind Morrison's submarine deal

- 'Sub-standard': Submarine deal botched by Morrison and his cronies

- Flashback 2019: Like a fish out of water: Australia's submarine project is a flop

- Nuclear sub plan sees Australia’s reputation take a dive

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.