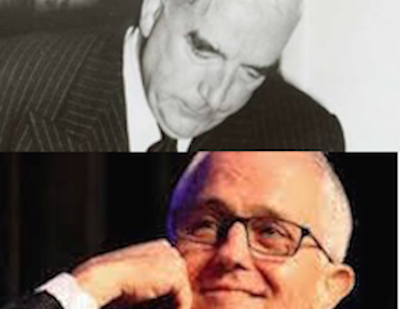

It's official: Malcolm Turnbull wants to be Bob Menzies, but the time is not right and he hasn’t got the required style.

The giveaway is the pompous mien; the confirmation is his declaration in London, in July, that Menzies, who “took pains” to call his new political party Liberal, not Conservative, was a man like himself — not like Tony Abbott.

Menzies, if a liberal thinker of any kind, kept it obscured by a bland exterior, more the devious man who realised that after the Great Depression and the Second World War, there was a liberal mood abroad he might be able to latch onto. As well, he might coast along upon an unexpected run of post-war prosperity, happening whether he was running the country or not. On top, there was the 1950s split in the Labor Party. These did give him a dream run.

At a cultural level "liberal", then, was "good", popular, opportune, a "third way", moderate, invoking humanistic ideas of kindness, reasonableness, fairness and equality, Roosevelt and winning the war, anti-Nazism, anti-racism, decolonisation, and – with Keynesian practices working well – also producing the post-war "miracle". It meant youth and future, peaking with JFK.

"Conservative" was "old", linked to wild capitalism that had caused the Depression and brought on Hitler. It backed prevailing but unfashionable social values: opposing the sexual revolution and standing up for God Save the Queen (a Menzies blind spot; he made a fool of himself over the young Queen and revelled in becoming a Knight of the Thistle). Billionaire entrepreneurs boasting how much they had and wanting to run state policies were absent. Those with millions kept quiet. Those running a family in the suburbs started to do alright.

Menzies – intelligent, a leader, cunning – caught the wave by grabbing the word "liberal" and watering down the idea. Some of his forerunners had been in the 19th Century party of that name, but from the 1940s those practising comprehensively liberal thought would have to start calling themselves small "L”, to be distinguished from all sorts of conservative wolves running about in liberal sheep’s clothing. Given the public mood, the motto would be "keep power by limiting change".

Consistently, he decided to be patient on policy, content to “create a climate for free enterprise”, through moderated and opportunistic state intervention — like when he made the first Federal Government foray into secondary education. The science block program for state and private schools pleased parents and fed into a drive for more science, which then, as now, was running a fever. In careful doling out of money, he also assisted baby boomer families by investing in child endowment and national health and pharmaceuticals schemes.

Then came the style part that evidently impressed young Malcolm Turnbull, aged 11, when the "Great Man" retired. Menzies, having got some middle ground, had obtained his electoral edge and could actually relax in office, strolling along fairly unchallenged, benevolent, magnanimous, maybe even grandiloquent. He dismissed the “socialists” but never let them get him down. If working class “yahoos” came to heckle at his public meetings he would give them repartee; those exchanges became a national sport. He was a great wit in Parliament. After Labor’s Deputy, impetuous young Gough Whitlam doused somebody at the despatch box with a glass of water, Sir Robert awaited his moment. Gough presently came to reach for a drink; Bob theatrically ducked under the table — haw haw haw, what witty fun!

For presiding over the country in times of prosperity with not much else happening, part of the grand style would be not to stoop to sustained hatred of "misguided" opponents, nor ever to look worried — as in the dangerous election year of 1961. One of the Menzies regulatory interventions – the 1960 "credit squeeze" – was so badly mistimed it generated a recession in Queensland.

Menzies campaigned nonchalantly around the State; he would wine and dine with the faithful then roll on, giving no sign of preparation, to one of the aforesaid rowdy public meetings. With the loss of eight Queensland seats, the second-last Menzies Government, like the Turnbull Government that eventually followed, had a majority of one. He would carry on blithely, after two years declaring a fresh election for the House of Representatives to get a majority — which he did, leaving Senate elections until the next year, he said, because “we didn’t want to make a mess”.

Making a virtue of mediocrity was a key point of the strategy. Sir Robert Menzies the lawyer and parliamentarian never said too much. You could think of him above the fray, stepping down to do some politics. He could act complacent even when sometimes getting dirty, looking for a good win, as with legislating to ban the Communist Party, or conscription for Vietnam — setting up a helpful khaki election for his successor.

Rarely, he’d get a bit emotional, usually to denounce Communism or praise the monarchy. Otherwise, the approach could be evasive, without curiosity, uninterested in arguing. At his last media conference, one journalist broke the celebratory mood to ask if he’d just been, not brilliant, but riding a wave of prosperity. He said if the question was whether he could ride a surfboard, no, but he got dumped once at Bondi — haw haw haw.

The successor Malcolm Turnbull is a talking-machine by contrast. As a key difference in style, we have this mixed persona, acting relaxed, then being more the shouter, putting on some inflated rhetoric, tackling critics, opponents, or casual bystanders of any kind — and impatiently persisting with a radically conservative, redistributive policy agenda.

He does face far less propitious times than the man he would be. Inside the Liberal Party in the old days, unruly boys on the right wing – the Barwicks and Caseys – could be pushed aside; not so easy today where the main trouble-maker is the immediate past prime minister. Among the public, we have, in 2017, a different, tricky mood with once-prevailing market fundamentalism: "neo-con" or "neoliberal" gone sour; no post-war economic boom to ride on, just climate change and ecological crisis; no Labor Party split, just an infuriating little guy there with numbers stitched up so tight he can’t be tossed.

The response is Prime Minister Turnbull’s double act: clambering up to be calm on the surface, smiling, promenading, shrugging, denying prime ministerially, like a Sir Robert; and, making potential bad friends with various groups of Australians who get in the way. These might include: High Court judges (announcing in advance what they would decide); people in South Australia (in their time of darkness, looking for words of encouragement, they got partisan talk about renewables); people who want to conserve Planet Earth (strike out carbon trading, stoke up old power stations, constrict the Reef conservation zones); members of trade unions (bastards and crims the whole lot); migrants (stiff-arm the asylum seekers) and so on.

Malcolm Turnbull the lawyer, but also merchant banker, has no real time for the 1960s; Menzies and half-baked economic management has but one key policy: get the numbers to get the corporate tax cut of $65-billion for a structural redistribution of wealth — have-nots to haves.

It is a yes to aping Menzies the grandee — actually no to Menzies' post-war liberalism.

Dr Lee Duffield is a former ABC foreign correspondent, political journalist and academic.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Read between the lines. Subscribe to IA for just $5.