When a trusted adult abuses a child, the cumulative trauma of decades of silence that often follow such injury is distinctly damaging, as Gerry Georgatos knows first-hand.

*CONTENT WARNING: This article discusses sexual assault

THREE YEARS ago, I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Only one in about 300 Australians live with Parkinson’s. Relatively, it’s rare. I’ve unknowingly lived with Parkinson’s for twice as many years since the diagnosis.

The diagnosing neurologist was surprised by my quiet calm. I heard a nameless sea of words. I don’t get over-sentimental or hard-hearted. I count blessings, embarking on journeys without deep pessimism about unpleasantness. It is futile to craft sorrow.

The sweet brief claim of life calls to me. Life’s heart flung open — I cannot close my mind’s eye to its soul. It has been said without shadows we have no light.

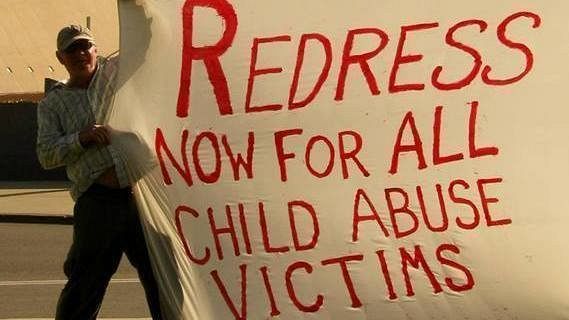

I have written before on Independent Australia, I was only nine years old when I was sexually assaulted by a man who, by all accounts, I should have been able to trust. The institutional setting was my primary school — the offender, a schoolteacher.

According to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, on average, males take 33 years to finally tell someone of such abuse. In my case, it was 47 years. Near four years ago, I finally told my partner and after that my only child. The telling was traumatic.

My father who loved me dearly passed away on Easter Friday 2014 and if he was still alive, I do not know if I could have told anyone what I told my two most loved ones. It was my view I could not break his heart and shatter a trust he had in the world — by showing it could be so unjust and cruel.

In 1971, I had nowhere to turn. That is because there was nowhere to turn to – not the institution of the school itself nor the police. My young years were lived in a time in the early 1970s of impenetrable hideous silences. There was hostility to such truth, whilst also widespread disbelief of such happenings. Such was indeed the times, as indelibly portrayed by the Royal Commission.

Nearly half a century would pass without my telling any other single soul. For a little while, years ago, I engaged a psychologist. However, even then I did not divulge it. I have never forgotten the psychologist’s inquiry, one which he persevered, as to the well of my strength and resilience. He commented he could not understand, knowing more of my life than others do, from where I had drawn the endless strength and resilience that he believed I had.

At times, I have wondered whether what cruelly affected me at age nine and the cumulative trauma of the long silence contributed to the neurological degeneration that is Parkinson’s disease.

I don’t know how my life story will end, however nowhere in my story will it read, 'I gave up'.

The late American civil rights advocate, James Baldwin said:

'Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.'

For the nine-year-old child betrayed, long were the days and nights of pain, the aloneness, the scattered thoughts. Too many children exist in lightning pain and dull-thud aches.

I reasoned — hide. Years passed and I realised — stay at the foot of the hills or climb them.

I decided no stranger or beloved should make one powerless and heavy-laden the heart. No wickedness should be my defining memory or speechless shadow. I found sanctuary in tomorrows and in quests of the uttermost.

Speak to me of love and I will follow. Speak to me of beauty and I will ascend. Let these direct my life’s course. Do not bind me in hate and wickedness. I want no bar of revenge in this small claim, life.

Speak to me of togetherness. Speak to me of living and of the good night’s sleep. Do not speak to me of anger and its torrents. Do not speak to me of slow deaths and savage restless nights.

After I first started to write and publish what happened to me when just nine years, I did see – eight times – another psychologist, last year. I do not profess absolute guarantee nor warrant, as universalisms, my views. I have always resisted being held hostage by trauma. I wanted to understand if others found me dissociative. She found me a contextualist, strong-willed, even if the rod of trauma was not spared.

I have never wanted to be a survivor, bent to earth by prayer. I want to remember each day as the beginning.

An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) showed up my brain with unexplained streams of white matter. My body is prematurely slowing. My right side shakes. My right arm does not swing. Rigidity has set. I can no longer type with both hands.

I am slow in unlocking a door or in paying at shop counters — sometimes to the evident impatience of cashiers. Graces I was blessed with are being taken, their time over. I speak of the pleasure in new worlds. I am thankful for the blessings I once experienced. I count new blessings and the dawn of new meanings.

I do not strive for an extraordinary life but for an honourable life. Where we marvel at coming alive each day. Where possible we support those who without support cannot achieve their best self.

I have found some of the most "damaged" people are the wisest counsel and the most empathetic. I have found many of them the kindest. Some of them are ultra-empathetic and transform lives because they do not want to see others suffer as they once did.

We stigmatise the poor, the homeless, the incarcerated and parents. We live with preposterous prejudices and criticisms of the poor.

I have worked to turn around the lives of as many people in gaol as I possibly could but for every inmate or former inmate people like me dedicate time to improving their lot, ultimately there is a tsunami of poverty-related issues and draconian laws flooding offenders, filling prisons.

Forgiveness is not an act of mercy but of empathy, compassion, of virtue. According to vast bodies of research, forgiveness has many benefits. Forgiveness strengthens families, communities and societies. The most significant finding is obvious — forgiveness makes us happier.

Forgiveness improves the health of people and communities. Forgiveness sustains relationships. Forgiveness builds and rebuilds lives. Forgiveness connects people — and what better medium for this than through kindness?

Australia has the financial trove to end all forms of homelessness, but governments lack the moral and political will.

If Australia was prepared to release its mentally unwell, either into community care or other specialist care, about 10,000 would walk out today. At all times we should be working closely, lovingly and forgivingly with those inside and so bring them out of the prison experience not worse but better.

I have spent a quarter of a century alongside the street-present homeless. Nationally, I have estimated the annual death toll on the streets of homeless people at more than 400 and sadly maybe well past 600. Their average age of death is mid-forties.

I have wondered how long I’d survive street-present homeless with Parkinson’s.

Australia has the financial trove to end all forms of homelessness, but governments lack the moral and political will.

Australia’s most vulnerable children are in juvenile gaols Australia-wide. I galvanised a class action against the brutal public spectacle of Banksia Hill Detention Centre (BHDC) to compel reforms.

Despite my Parkinson’s Disease, I count my blessings. The calling to do away with children’s prisons is worth every particle of strength left in me.

If you would like to speak to someone about sexual violence, please call the 1800 Respect hotline on 1800 737 732 or chat online.

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus on social justice. You can follow Gerry on Twitter @GerryGeorgatos.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.