As visa changes are likely to continue the influx of migrants, the Government is prioritising low-skill work that doesn't guarantee the rights of migrant workers, writes Dr Abul Rizvi.

IN RESPONSE TO a combination of supply chain issues and labour shortages partly due to impact of the Omicron variant, the Morrison Government last week made a flurry of temporary entry visa policy changes.

What impact can we expect from these and what is the baseline we should use to assess these?

In November 2021, the Morrison Government announced it would open international borders for a range of temporary and permanent entry visa types from 1 December 2021. While this was postponed to 15 December 2021, the announcement had an impact on both arrivals and departures.

Provisional data for December 2021 shows arrivals increased to 196,810 while departures increased to 229,380. These were by far the highest level of arrivals and departures since the start of the pandemic.

The departures were dominated by Australian citizens and permanent residents as the stock of temporary entrants in Australia increased from 1,643,000 at end September 2021 to 1,665,000 at end December 2021.

The increase was driven by a sharp increase in visitors from 38,728 at end September 2021 to 66,583 at end December 2021. These would be predominantly people visiting family as international borders are not yet open to general tourists.

There was also an increase in temporary entrants in the "other" category from 46,479 at end September 2021 to 53,611 at end December 2021.

A contributor to this would have been a large contingent of sportspeople, support staff, media and so on associated with the cricket and the tennis. Another contributor would have been seasonal farm workers from Pacific Islands.

The stock of skilled temporary entrants fell from 95,035 at end September 2021 to 90,737 at end December 2021. This would partly have been due to some skilled temporary entrants securing permanent residence, as well as departures of these highly mobile people outstripping arrivals.

Arrivals of skilled temporary entrants in the March quarter of 2022 should increase with the current high level of job vacancies and very low levels of unemployment amongst skilled workers. Visa grants to offshore skilled temporary entrants in the December quarter of 2021 were 6,056 compared to 3,823 in the December quarter of 2020.

Onshore visa grants to skilled temporary entrants only increased from 7,367 in the December quarter of 2020 to 8,484 in the December quarter of 2021. This suggests a continuing low transition of temporary graduates to skilled temporary entrants and should be of ongoing concern to Government, the international education industry and education quality regulators.

The number of overseas students in Australia fell from 317,915 at end September 2021 to 315,949 at end December 2021. In more normal times, there is a substantial departure of overseas students in the December quarter as they complete their courses or go home for the academic break.

Offshore student visa applications lodged in the December 2021 quarter were 38,872 compared to 26,386 in the same quarter 2020. This increased application rate, together with a large cohort of overseas students granted visas over the past 18 months but unable to enter, should result in a substantial increase in student arrivals in the March quarter of 2022.

Temporary graduate visa holders in Australia increased only marginally from 95,042 at end September 2021 to 95,259 at end December 2021. These people are increasingly finding themselves in immigration limbo, as a large portion continue to be unable to secure skilled jobs that provide a pathway to permanent residence.

Working holidaymaker (WHM) and work and holiday (W&H) visa holders in Australia fell from 29,821 at end September 2021 to 19,324 at end December 2021. Some of these may have secured permanent residence or another type of temporary visa while others may have departed. There would have been a minor increase in working holiday maker arrivals in the last two weeks of December 2021.

There was a dramatic increase in offshore WHM visa grants from 236 in the December quarter of 2020 to 13,107 in the December quarter of 2021. Similarly, offshore W&H visa grants increased from 55 in the December quarter of 2020 to 1,643 in the December quarter of 2021.

This will likely result in a large influx of these visa holders during the March quarter of 2022.

Finally, there was a small increase in bridging visa holders in Australia from an already astonishingly high 330,808 at end September 2021 to 333,357 at end December 2021. It seems the Department of Home Affairs is giving no priority to processing the backlog of bridging visa holders although there was a small increase in processing of the very large primary level asylum seeker backlog (most of whom would be on bridging visas) in December 2021.

That situation is likely to continue into the March quarter of 2022 when there will be pressure to process a large increase in offshore applications. It is also possible the Government will announce a larger number of skilled independent invitations in response to pressure from business lobby groups.

Policy changes to attract temporary entrants

In early January 2022, the Government announced a flurry of policy changes to attract more temporary entrants in Australia and to retain skill stream provisional visa holders.

Minister Alex Hawke said that:

'The Government will extend by three years skilled regional provisional (subclass 489, 491 and 494) visas where the visa holder was impacted by COVID-19 international travel restrictions. This will assist around 10,000 skilled regional workers.'

Presumably these visa holders are offshore and may return to Australia in the next few months.

Hawke also announced that:

The Government will make changes to allow entry of current and former temporary graduate (subclass 485) visa holders from 18 February 2022, to allow them to re-enter Australia and apply for a further stay. Visas will be extended for graduates who were outside of Australia at any time between 1 February 2020 and 14 December 2021, while they held a valid Temporary Graduate visa.

These changes support the return to Australia of temporary graduates as soon as possible, ahead of further planned changes on 1 July 2022 that will provide a further visa extension option to former graduates.

How a visa extension will be given to temporary graduates whose visas have already expired is not clear. This may require a regulation change.

The Government also announced that students and WHMs who arrive in the next 12 weeks will have their visa application fees refunded. This is likely to predominantly benefit students who already hold a visa or were going to apply shortly and enter before the start of the next academic year. The key will be availability of suitable and affordable flights.

Students now have unrestricted work rights in terms of hours and where they work. This will effectively transform student visas into low-skill, unsponsored work visas. It will attract students interested in low fee courses with limited study and attendance requirements.

WHMs can also now work with the one employer for the full 12 months. This was previously restricted to six months. During my time in the Department of Immigration, WHMs were restricted to working no more than three months with the one employer. The objective was to encourage WHMs to travel around Australia with a focus on holidays as much as work.

The WHM visa has also effectively become an unsponsored work visa with holiday now entirely incidental.

The WHM visa for UK nationals will be a three year visa with no requirement to work in agriculture. Other WHM agreement nations may argue for a similar arrangement for their nationals.

The above changes are in addition to an expanded Pacific Island seasonal worker scheme, the new agriculture visa and the massive labour trafficking scam of recent years to fill farm labouring positions.

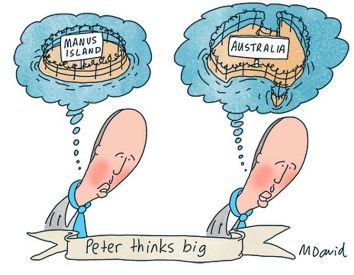

The Government is increasingly focused on using temporary entry visas to fill low skill roles in manner that was anathema just 15 or 20 years ago, but without any genuine strengthening of provisions to protect these workers from exploitation and abuse.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

Related Articles

- Immigration reform must respect migrants' rights and drive economic growth

- Australia’s weak labour market causes NZ migration slump

- New visa for migrant farm workers could turbocharge exploitation

- Perrottet pushes mass migration harder than Morrison

- Update of Australia’s biggest ever labour trafficking scam

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.