With so many vulnerable Australians relying on quality public health care, a government claiming to uphold Christian values would do well to contemplate the timeless question: what would Jesus do, writes Dr Benjamin T. Jones.

ON THE EVE of the 2013 election, the devoutly Christian Tony Abbott infamously declared that his government would, among other things, make no cuts to health. It was one of a string of promises audaciously and unashamedly broken almost immediately after assuming office. With a new election looming, the future of Medicare is again set to be a key campaign issue.

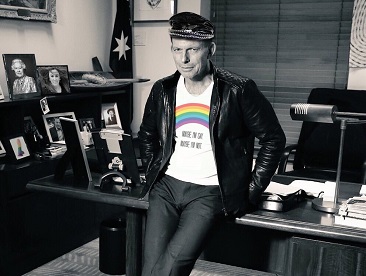

The prime minister may have changed since 2013, but the Liberal Party’s ideological commitment to trimming Medicare has not. With Malcolm Turnbull at the helm, the health budget is set for a $650m cut with pathology and diagnostic imaging tests particularly targeted. These cuts disproportionately hurt low-income earners who rely the most on public health. With so many calls in the Bible to help the poor and the sick, it is with no small irony that these cuts come from a government which habitually trumpets its Christian credentials.

Although criticised at times for duplication and inefficiencies, Australia’s health system is one of the best in the world. Australian men have the third highest life expectancy of any nation with women sixth highest, according to the World Health Organisation in 2014. It seems strange then that the most overtly Christian Australian Government in the last half century used its very first budget to dislodge the concept of universal healthcare.

Elected in September 2013, Abbott, perhaps more than any other prime minister, incorporated his religion into his politics. Defending his tough border policy stance as opposition leader, he said:

“Jesus knew that there was a place for everything and it’s not necessarily everyone’s place to come to Australia.”

Critical of the carbon pricing scheme introduced by Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Gillard, he called on the previous government to “repent”. While education funding was cut in Abbott’s first budget, it is significant that the Federal chaplaincy program was continued, but with the proviso that non-religious counsellors be excluded.

In Abbott’s initial 18-man (and one woman) cabinet, Catholics held senior portfolios, including treasurer, finance, trade, communications, education, agriculture, and social services ministers. The remaining ministers belonged to a range of Christian denominations, with none identifying as an atheist. Given the overtly Christian makeup of the Coalition Government, it was perhaps surprising that their first budget, in May 2014, included a proposed $7 co-payment to see a general practitioner, which would have ended 30 years of free universal healthcare. To prevent people avoiding the payment by going to hospital instead, the Government also allowed the states to introduce a $7 fee for emergency visits.

The fiscal value of the scheme was immediately questioned, with the head of the Australian Medical Association, Brian Owler, warning that:

“For some people this copayment ... could act as a deterrent and the eventual effect of that will be that overall medical costs increase rather than decrease.”

Director of the Deeble Institute for Health Policy Research, Anne-marie Boxall, has suggested the co-payment would

'... be an unfair burden on people with lower incomes, who also tend to be in poorer health and are most likely to defer visits to the GP because of cost.'

Following a vicious public backlash, plummeting polls and difficulty passing the legislation through the Senate, the Government introduced a modified version in December where GPs would lose $5 from the Medicare rebate but had the option of passing this on to patients. This too failed to receive support, either from the public or Senate.

Abbott introduced a second woman to cabinet when Sussan Ley was promoted to minister for health. In March 2015, she declared all co-payment plans were finished, but opponents remained wary. The recent spate of cuts under Turnbull have been condemned as co-payment by stealth.

A freeze on rebates is co payment by stealth #ausvotes2016 #auspol pic.twitter.com/lWTdVkFNMd

— Misty Eyed Leo (@Loud_Lass) May 10, 2016

John Rawls is a secular philosopher who can be instructive when contemplating a topic like universal healthcare. Rawls abandoned orthodox Christianity as an American soldier in World War II, but identified as a non-theist, rather than atheist. In his classic 1975 work, A Theory of Justice, Rawls looks for moral reasoning that does not rely on God’s existence and supports, among other things, the concept of the veil of ignorance. Put simply, when we argue or take a position on ethical issues like healthcare we, consciously or not, speak from our position as members of a certain race, gender, religion, socio-economic group, and a host of other variables relating to intelligence, ability and education.

Rawls attempts to negate these factors using a thought experiment where

'... no one knows his place in society, his class position or social status; nor does he know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence and strength, and the like.'

Another way to imagine it is; what if you went back before you were born? You did not know if you would be rich or poor, male or female, intelligent or not.

If this was the case, if we made decisions from behind a veil of ignorance, what policies would we want implemented?

Rawls favours the veil of ignorance method because participants

'... do not know how the various alternatives will affect their own individual case and they are obliged to evaluate principles solely on the basis of general considerations.'

Given the percentages and possibilities before entering society, what kind of system would you judge as fair?

The veil of ignorance forces us to put aside our personal circumstances. Like the classic board game, The Game of Life, we sit back at the table acutely aware of the various possibilities and the element of chance. Statistically, only a precious few will ever be born into great wealth or be intelligent and able enough to gain it. At the other end of the social ladder, more than 2.2 million Australians – including 600 000 children – live in poverty (roughly one in eight).

Further, a Griffith University study has recently suggested

'... the poorer, younger and less educated parents are, the more likely babies are to end up at the doctor sick or injured.'

We're old, we're living in poverty, & our government does not care about us. Liberal Australia. pic.twitter.com/MMgaWA9hdX

— Human writes (@ianw84) May 8, 2016

Given all this, if you were about to be thrust into society, what would your attitude to healthcare be? Would you prefer a universal system where your medical needs are taken care of, even if you draw every short straw and are born into the most unfortunate circumstances possible? Or would you take a risk and hope that, if not your economic circumstances, at least your natural faculties would be adequate to let you negotiate a blunt capitalist system?

The politics behind the Medicare co-payment is nuanced and reactive to a host of competing factors tied to the electoral cycle. Of significance here is not the inner workings of the political class, but the ideology behind the conservative Christian Right in opposing universal healthcare. There is a principled objection to people getting something for nothing and a stigmatisation of any who take government help as lazy and parasitic. In sum, people should not get something they do not deserve.

The glaring irony here is that the entire premise of Christianity is that God’s grace, love, and forgiveness is extended to sinners who do not deserve it. For Marx, a religious dimension was not necessary. Shared humanity was reason enough to tend to the sick, so he rallied against a system of stratification that saw people only receive the care they could afford. How much more so for Christians, who have the theological imperative that all are created in God’s image and a religious obligation to care for the sick?

To some extent the God of the Religious Right has been created in their own image and affixed to the gospel are the new virtues of capitalism, competition and consumerism. The cultural demonisation of Marxism is complete to the point where his congruencies with large sections of the Bible become irrelevant. Indeed, those sections of the Bible become irrelevant also.

With the prospect of a double dissolution election, control of the upper house is up for grabs. Should the Coalition be returned, they may well be able to pass a raft of legislation unencumbered by a hostile Senate. With so many vulnerable Australians relying on quality public health care, a government claiming to uphold Christian values would do well to contemplate the timeless question: what would Jesus do?

This is an excerpt from 'Atheism for Christians: Are There Lessons for the Religious World from the Secular Tradition?' The book launch is Friday 13 May in Glebe, Sydney.

More information at www.atheismforchristians.com.

Dr Benjamin T. Jones is an adjunct fellow at the School of Humanities and Communication Arts at the University of Western Sydney. You can follow Dr Jones on Twitter @BenjaminTJones1 or on his blog, Thematic Musings.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Govt faces a GP revolt worse than the Abbott co-payment uprising https://t.co/owu4oWIX3o Sorry by now you voted #LNP, colleagues?

— Ming The Merciless (@MGliksmanMDPhD) May 10, 2016

Investigate Australia. Subscribe to IA for just $5.