Will the Morrison Government use this budget to move forward and embrace the opportunities of a post-carbon global market or take Australia back to the “dog days”? Emma Dawson discusses the Treasurer's recent shift in rhetoric.

MUCH HAS BEEN MADE of Josh Frydenberg’s pre-budget speech last week (Thursday, 29 April), in which he made a sharp turn away from years of Coalition rhetoric about the dangers of budget deficits and, apparently, embraced expansionary fiscal policy to drive unemployment down below pre-pandemic levels.

That the Treasurer’s speech was interpreted as a fundamental change in direction by the Morrison Government exposes the extent to which the national hysteria over "debt and deficit" – so brutally wielded by then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott in the wake of the GFC – has infected our economic debate.

What Frydenberg announced in this speech was really nothing more than an unremarkable shift in the calculation of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) by Treasury, and one that was long overdue. Many leading economists have been calling for a rethink of the NAIRU for years and some have now moved much further than Treasury’s estimate of between 4.5 and 5%.

Distinguished Australian economists Ross Garnaut and Justin Wolfers have recently urged the Government and the Reserve Bank (RBA) to drive the employment rate down as far as possible, to the point at which inflation starts to pick up; both agree that this is likely closer to 3% than 5%. The point is that we don’t know what the NAIRU is until we get there and, if and when we do, we can manage any resulting inflation through tried and tested monetary policy measures. In the current economic circumstances, there is simply no excuse for not pursuing genuine full employment as the central goal of our economic reconstruction.

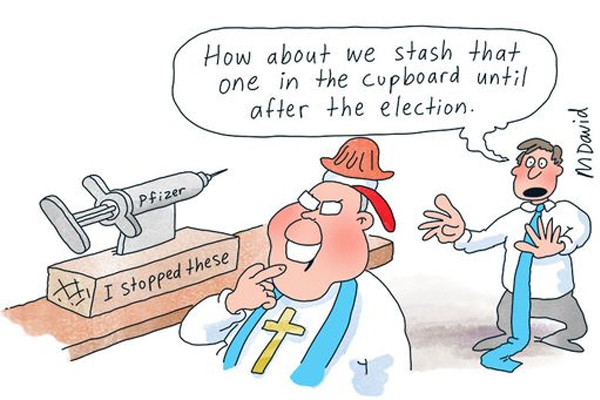

Nevertheless, the Treasurer’s explicit rejection of "austerity" policies that would prioritise balancing the budget is a welcome development, if not an extraordinary one. This budget is not just the first of the reconstruction phase following the COVID recession. It is a pre-election budget, meaning the kinds of savage cuts to services required to promise a return to surplus over the forward estimates would likely be political suicide.

Yet there are plenty of reasons to worry that the fiscal reality revealed when Frydenberg hands down his third budget next week will not match the rhetoric of recent days. Given that the deficit for 2021-2022 is projected to be around $50 billion, a massive reduction in government spending of at least $100 billion compared to the current year is already baked into Budget 2021.

JobKeeper payments stopped at the end of March and JobSeeker was cut back by a further $100 a fortnight to just $620 — a full $500 less than it was at the height of the pandemic. We are yet to see the full impact of these spending cuts play out across the economy and, given the forecast $100 billion reduction in government spending, it appears the Government is not planning further measures to provide direct income support to households.

Absent such government support, a focus on reducing the headline unemployment rate will likely be insufficient to drive growth and economic reconstruction. So far, the majority of jobs that have returned since the height of the recession have been part-time, with full time positions still well behind pre-COVID levels. Under-employment is likely to remain high and it is this slack in the labour market – the number of people who may have a job but are seeking more hours of work – that has been primarily responsible for the stagnation in wage growth over recent years.

Yet the Government seems to have no plan for wage growth — apparently, in fact, quite the opposite, having thrown its weight behind business demands to minimise and delay any increase to the minimum wage. In its own submission to the Fair Work Commission’s Annual Wage Review, currently underway, the Government has argued that lifting the hourly rate paid to Australia’s lowest-income workers would impose a ‘major constraint’ on the nation’s economic recovery.

This reasoning is at odds with Treasury’s embrace of a lower unemployment rate as a means to drive growth: it matters not just how many jobs are created, but that those jobs are reliable, secure and well-paid. Well over half of Australia’s economy relies on consumer spending and consumer spending isn’t driven by employment growth, but by household income growth. If people don’t have enough hours of work, or if their hourly rate of pay is insufficient to meet the growing costs of living, they won’t have sufficient money to spend into the economy — security is critical to confidence.

The question to be answered by next Tuesday’s budget is whether the Morrison Government means to undertake serious economic reform and investment to both reduce unemployment and lift wages, or whether the recent anti-austerity rhetoric signals merely that it will postpone selling assets and cutting spending for a year or so before returning to the reckless pursuit of budget surpluses at the expense of household living standards and economic security.

The 2021 Federal Budget could well be the most important in a generation. It will set the direction of Australia’s future economy: either back to what Garnaut calls the “dog days” of the pre-pandemic years – when investment and innovation stalled, wages stagnated and living standards began to decline – or forward to drive investment in new and emerging industries and embrace the opportunities of a post-carbon global market for sustainable goods and services.

It will also set the scene for the next federal election. With the pursuit of budget surpluses perhaps no longer the great shibboleth by which we measure economic management, maybe we can hope for a genuine contest over policies. Policies that will create good, secure jobs, diversify our limited industrial base, lift pay and conditions for essential workers, and build a sustainable, equitable and dynamic economy for future generations.

Emma Dawson is an IA columnist and executive director of Per Capita.

Related Articles

- Questions remain over Frydenberg's claims on ASIC expenses scandal

- ABUL RIZVI: Frydenberg’s long-term GDP forecast will drive policy thinking

- ABUL RIZVI: Predictions for Josh Frydenberg's Intergenerational Report

- Josh Frydenberg is playing dumb on the big banks

- Canberra economists expose the Coalition’s economic failures

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.