A national tax on the extraction and sale of natural resources could be used to invest in a better education system, writes Emma Dawson.

THE AUSTRALIAN SENATE is currently conducting public hearings as part of an Inquiry into Australia’s Oil and Gas Reserves. Originally referred to the Standing Committee on Economics in September 2019 with a report to be tabled by March 2020, the inquiry has been extended four times and is now expected to provide its report to the Senate by 2 December 2021.

In its one hearing before the original reporting date, the Committee heard only from witnesses representing various government departments and agencies charged with regulating Australia’s resource sector, including the ACCC, Geoscience Australia and the Federal Departments of Treasury and Industry, Science, Energy and Resources.

In these current hearings, however, witnesses have been called from a range of independent research and advocacy organisations who made submissions to the Inquiry almost two years ago, including Per Capita. I joined witnesses from The Australia Institute and Prosper Australia at the hearing on 20 August, in which all questions came from the Independent Senator for South Australia, Rex Patrick, and none from the members of the Committee representing the major parties of the Parliament.

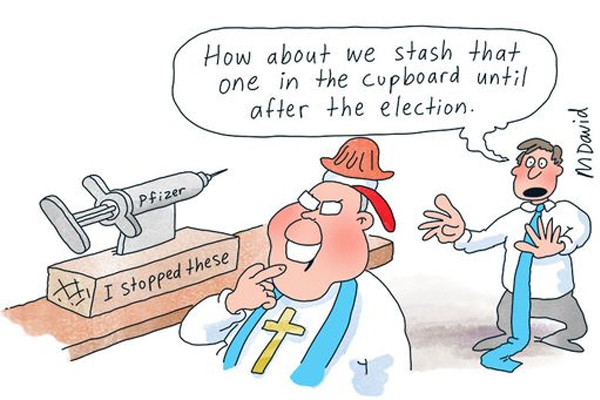

Neither major party wants to talk about tax reform before the election. Labor has dropped its signature tax policies from the Shorten years and has reluctantly acquiesced to the Coalition’s only economic policy: to remove another $17 billion a year in government revenue and hand it back to the nation’s highest income earners.

But with record levels of government debt and the need for significant government spending to support our economic recovery from COVID-19 and decarbonise the economy, whoever wins that election will have to grasp the mettle of structural reform to deliver a sustainable tax base.

Taxing the extraction and sale of natural resources, or “economic rents”, is the most obvious and lucrative option available and one that any politician worth his or her salt should be able to sell to the Australian people.

That we receive so little recompense for the extraction and export of our natural resources is indefensible. Australia is one of the most resource-rich nations on Earth; besides being the world’s leading exporter of coal, we hold a top-five position as the producer of another 19 commodities, not all of which are carbon-emitting fossil fuels. In early 2020, we overtook Qatar as the largest exporter of Liquid Natural Gas in the world, yet Qatar takes in around 20 times the tax revenue from its LNG exporters as does Australia.

Exporters of our natural resources are essentially engaged in asset sales. These assets – which can only be sold once – belong to all Australians and the failure of our taxation system to secure a reasonable share of their value for the common good is an abject failure of policymakers.

In 2018, a submission to the Senate Economics References Committee Inquiry into Corporate Tax Avoidance demonstrated the scale of foregone revenue, rightly owed to the Australian people, resulting from our nation’s extraordinarily lax fiscal and regulatory regime.

Juan Carlos Boué, a researcher at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, calculated and compared the Effective Tax Ratios (ETRs) for petroleum exploration and production activities in different jurisdictions producing oil and natural gas and found that, since 2008, Australia has imposed an ETR of 21% on gross industry income from petroleum exploration and production.

Boué found that:

“If the quantum of gross income generated by upstream oil and gas activities in Australia during these years had attracted the ETRs which oil and gas activities attracted in Denmark and Norway during this same period (49 and 54%, respectively), then the Australian Federal Government would have received an additional 71 or 84 billion U.S. dollars, respectively, in fiscal income.”

That’s more than double the cost over a decade of fully funding the original Gonski education plan.

If we are to continue allowing multinational mining companies to extract and export our non-renewable energy resources, we should be demanding a much higher return, which we can invest in our future prosperity. The best way to do that is to lift investment in public education.

The increased government revenue gained from a uniform national resource rent tax, implemented at an internationally competitive rate significantly higher than our current 21% ETR, could underpin a long-term investment vehicle that could secure public education funding and rescue it from the political tug-of-war that sees our poorest schools fighting for scraps from general government revenue.

The proceeds from the uniform national resource rent tax should be spent initially on directly funding the Gonski school education plan, with the remaining revenue wholly invested in a new sovereign wealth fund dedicated to funding school education.

The Education Future Fund could be administered alongside Australia’s other sovereign wealth funds, by the Future Fund, or by a new independent authority. Managed prudently, its proceeds could, within a decade, sustainably fund Australia’s school education sector in perpetuity.

Seems like a no-brainer, doesn’t it? So why are our political leaders so unwilling, or unable, to impose the same taxes on economic rents that are widely implemented and successful in other resource-rich nations?

The answer is to be found in the fate that befell the Rudd Government’s disastrous attempt to implement a Minerals Resource Rent Tax in 2010, which was itself a diluted version of the uniform national resource rent tax proposed by Ken Henry the previous year.

Facing trenchant opposition from the mining industry, which ran a well-resourced scare campaign backed by then-opposition leader Tony Abbott, Rudd’s signature tax policy fell at the first hurdle and was a major contributing factor to his ousting as Prime Minister in June that year. It was then resurrected by Julia Gillard, but with concessions to the mining industry so extreme as to render it virtually useless as a source of revenue.

A decade later, it seems that Senator Patrick is on a crusade to persuade the Parliament that the time is right to try again — and all power to his arm.

Of course, opposition from the Australian mining sector to the prospect of reasonable taxation of economic rents would, again, be fierce, but it’s doubtful that a campaign against a well-designed resource rent tax would find as receptive an audience as it did in 2010.

For a start, public opinion on issues of tax and transfer has shifted considerably in the intervening years. The annual Per Capita Tax Survey, which has been conducted since 2010, has seen a marked increase of more than 10% in the number of Australians who believe that corporate tax avoidance is unfairly skewing our tax system since the survey commenced.

The survey reflects a growing concern amongst the electorate over growing inequality in Australia. A tax and transfer policy that sought to recoup our fair share of the proceeds from resource asset sales for investment in the education of our kids and our future workforce would likely find favour with citizens concerned about low wage growth, high house prices and increased costs of living.

Secondly, the mining boom is over and an industry campaign against a “great big new tax” would likely fall on fallow ground. Its success in 2010 was due to the industry’s ability to portray itself as a major employer and a strong investor in the Australian economy.

But since 2012, employment in mining has fallen by around 20% and mining investment, which peaked that year at around 9% of GDP, has fallen rapidly to below 4% of GDP today.

It’s much harder for mining billionaires in 2018 to make the case that a tax on their business profits is a tax on the incomes of working Australians. The failure of the Business Council’s campaign for company tax cuts for businesses with more than $50 million in revenue to cut through to the Australian people shows that times have changed.

Thirdly, a well-designed uniform national resource rent tax, explicitly aimed at funding education rather than at shoring up the general revenue base, would appeal to a demonstrated desire among the public for increased investment in our education system.

Four in five Australians want to see more government spending on education. Along with health, it’s an area the vast majority of Australians, of all political persuasions, believe deserves greater investment.

Finally, if the proceeds of the tax were invested securely in a sovereign wealth fund, the populace could be convinced that their money, coming from the sale of their assets, was being prudently and independently invested for the betterment of their and their children’s futures.

In short, the politics of selling such a policy should be achievable for any politician serious about reducing inequality and investing in the future of the nation.

A properly structured uniform national resource rent tax is long overdue. By using it to create an independent sovereign wealth fund to secure the future of our education system, policymakers could create a widely supported, sustainable means of ensuring that Australians will share in the proceeds from the sale of their nation’s natural assets for generations to come.

Emma Dawson is an IA columnist and executive director of Per Capita. You can follow Emma on Twitter @DawsonEJ.

Related Articles

- Shareholders could reap benefits of Morrison's Ampol bailout

- Fossil fuel giants hit by court rulings over climate impacts

- NSW Government misleading with 'green hydrogen' claims

- Malcolm Turnbull lashes out at right-wing media over coal advocacy

- The gas-fired recovery swindle

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.