Further reform is needed to tackle the depth of misconduct shaming Australian politics, other than just launching an integrity commission, writes Dr Tim Dunlop.

IN AN ARTICLE written before the last Federal Election, journalist George Megalogenis made one of his characteristically wise asides, saying:

‘There is an unfortunate reflex in our politics – from those who practise it to those who analyse it for a living – to seek American or British analogies for our polarisation.’

In praising his insight, however, I am about to ignore his advice.

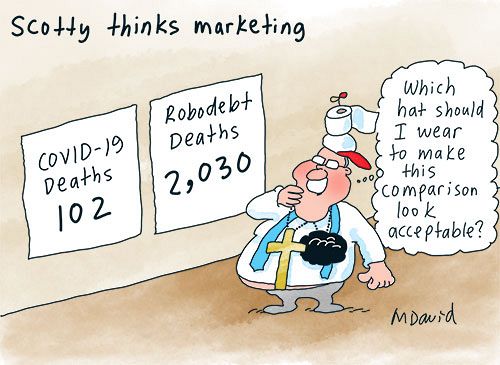

Scott Morrison never produced anything so dramatic as the Watergate break-in, but there is no doubt that his approach to governance left in its wake a number of problematic legacies.

We know all about the "stroll out" of the COVID-19 vaccine and the equally slow response to the need for home rapid-antigen tests once the Omicron variant appeared. We know about his government’s failure to distribute funds in the wake of fire and floods, let alone do anything tangible about the climate change that caused them in the first place.

We also know that on his watch, Centrelink – in the form of the so-called robodebt debacle – raised, as a Senate report noted, ‘$1.73 billion in illegitimate debts… against approximately 433,000 Australians...’

The report notes that:

‘... approximately 381,000 [of these] individuals were pursued, often through private debt collection agencies, to repay almost $752 million to the Commonwealth.’

This persecution of welfare recipients continued until ‘the Federal Court of Australia confirmed that the Government had no legal basis for pursuing these debts’.

We know about the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety; the 148 recommendations it made for improvements and that, even before the report was released, commissioners Tony Pagone QC and Lynelle Briggs had criticised the Morrison Government for failing to properly monitor COVID outbreaks in aged care facilities.

Pagone and Briggs said that, had:

"... the Australian Government acted upon previous reviews of aged care, the persistent problems in aged care would have been known much earlier and the suffering of many people could have been avoided."

We know the 2020 report by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) on $100 million dollars worth of funds provided as grants to various sporting organisations around the country, found that the ‘award of grant funding was not informed by an appropriate assessment process and sound advice'.

We know that the Royal Commission into misconduct in the banking, superannuation and financial services industry turned up instances of deep malfeasance.

More disturbingly, according to journalist Adele Ferguson, it showed that:

‘The banks’ powers rested not just in the profound wealth they were probably producing, but also in the deep connection between the banks and the political establishment.’

This sort of state capture, as it is called – an ongoing, unhealthy relationship between government and business – pervades Australian governance, something spelt out in two recent reports, 'Selling Out: How powerful industries corrupt our democracy', produced by the Human Rights Law Centre, and 'Confronting State Capture', written by the Australian Democracy Network.

This is quite a list — and all this before an integrity commission even exists.

The parallel I am drawing, against George Megalogenis's advice, is not with the Watergate break-in, but with what happened in the United States Congress in the wake of Nixon’s resignation.

According to John Lawrence – the longest-serving staffer on Capitol Hill – at the time of his retirement in 2013, Nixon’s criminality led to an influx of new Congressmen (mainly men) who instigated a series of reforms that changed the way Congress worked.

In a recent article, Lawrence writes that:

... only 12 weeks after Nixon had resigned the presidency and ruined the Republican brand, the nation went to the polls and chose a very different type of political leadership. The Class of 1974 — particularly in the House of Representatives — was younger, less deferential to seniority, more liberal on policy matters and more activist in demeanour than the sclerotic Congress they joined.

"We were a conquering army,” recalled freshman George Miller of California, who at 29, was closer in age to anti-war demonstrators in the streets than the average age of House members.

Similarly, concern about political malfeasance in Australian politics was one of the issues that drove the influx of new members (mainly women) into the Australian Parliament on 21 May and they, too, are promising a raft of reforms.

The parallel is not perfect, not least because the transformation we saw in Australia is, if anything, a more far-reaching one than what happened in the U.S. in 1974, but I think it might be useful to remind our Class of ‘22 that there is, not just a precedent for bold action, but a warning from the U.S. — that unless you bed down serious reform, worse is waiting, as the current 6 January hearings in the U.S. Congress attest.

What is clear, I think, is that an integrity commission will not be reform enough.

The astounding thing is that we managed to leverage the change of 21 May 2022 within the confines of a system that inherently favours the status quo — the preferential voting system tending to channel votes back to the major parties.

We would do well, then, to consider what might be possible with a proportional system of voting that better aligns the number of votes cast with the number of seats allocated on the floor of the House.

And we might also consider the idea of institutionalising the methodology of community engagement used by the "Voices Of" model and allow citizens chosen by sortition to involve themselves in policy negotiations at the highest level.

As the new Parliament prepares for its first sitting, we citizens and our newly elected, unprecedently diverse representatives need to seize the moment.

This article was originally published on Eureka Street under the title 'Can the class of '22 fix Australian Democracy?'.

Dr Tim Dunlop is a leading author and professional speaker specialising in media, technology and the future of work. You can read more from Tim here and follow him on Twitter @timdunlop.

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- Working class moves Left under conditions of crisis

- ELECTION LIVESTREAM HIGHLIGHTS: Dr Tim Dunlop and Professor Kerryn Phelps

- Mayhem at the democracy sausage stall

- CARTOONS: Voting for the cream of the crop — a tip

- What the top 2022 Federal Election issues tell us