A common theory that there are bounteous employment opportunities in Australia is incorrect and governments, the media and economists must do more to secure our economic future. John Haly reports.

This is a familiar theme on social media, exemplified by this quote from Twitter:

‘There is enough work in Australia for nobody to be on unemployment benefits except for those medically incapable.’

Such claims are often made, predictably, by a privileged White male with a job and no understanding of the misery of the unemployed because he has some anecdotal “proof” based on his personal experience of how his “mates” have kept him in work. Outside of that cocoon, as my recent piece demonstrated, there are far more unemployed people than the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has ever stated. However, the notion that bounteous employment is available prevails.

According to Roy Morgan’s research, full-time and part-time employment are increasing, but so are underemployment and unemployment rates beyond 2021. There are numerous reasons from my last exposition on this using October 2023 statistics to believe that one and a half million people are validly unemployed. This is significantly more likely than the claim of around half a million that has dominated the ABS estimate over the last year. I’ve already addressed that, so let’s move on to the subject of work opportunities in Australia.

Understandably, having a low unemployment rate serves corporate and government interests. There is strong motivation to find a high number of vacant positions to support the narrative that the unemployed are simply unmotivated, preferring to live off grandiose welfare cheques. The idea of below-poverty aid being sufficient to propel individuals into occupations clamouring to be filled by desperate employers is ridiculous. Unfortunately, so many people think this is true.

Despite the ideological incentives, data from the ABS and estimates from the Department of Employment show that job opportunities have decreased in recent months. Businesses report a 35% higher number of job positions than the number of classic job advertisements as identified by the Department of Employment (see Figure 1). This is despite the drive for a narrative that implies there is enough employment.

However, all the Government can come up with is a little over 402K job positions. Only two-thirds of these are classically advertised. This is still less than the half million ABS estimates are unemployed. In October 2023, Nine News featured headlines like ‘The Aussie industries desperate to hire more workers’. If this is the case, why are there so few advertisements in comparison to claimed vacancies? Figures 1 and 2 both show that over a decade ago, surveyed jobs were less than advertised positions.

There are reasons for this, to be fair, which are because of developing technologies. Seek, CareerOne, JobSearch, LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter/X have emerged as key outlets for job seekers and employers in the digital era. The final three are not tracked by the Internet Vacancy Index (IVI) statistics. However, because of the abundance of inflated and outdated profiles, LinkedIn’s popularity has declined dramatically over the years as has Twitter/X. Hey, I glam my LinkedIn up as well, but I haven’t heard from a recruiter in years.

The claim by businesses that surveyed vacancies are 35% above advertised positions appears dubious. If 35% of the total 402K positions indicated in the poll are not easily accessible for public scrutiny, we must wonder what kind of job market is being concealed from the public. It will almost definitely not be general labourers (5.8%), drivers (5.3%), salespeople (7.3%) or community workers (10.7%) (see Figure 3).

The service industries, which have been complaining about being “desperate for workers”, will promote heavily. There are 76K jobs in that small group, which is distributed across Australia’s vast brown country, with 18 cities, over 100K inhabitants, and 1,700 towns with populations ranging from that to a thousand people. The math suggests that if there are more than 40 job vacancies in a given location, you are most likely in a metropolis. If you are in a rural area with fewer than a thousand people, the chances of finding one job in all of those categories are slim. I haven’t even mentioned whether you have the skills to perform these non-professional occupations.

Professionals, managers, technicians and clerical and administrative staff vacancies (which make up the great majority of posted jobs) that require expensive higher education are the most likely categories to find unadvertised job vacancies. If you disagree, take a look at Figure 4 for a breakdown of the ABS survey of positions by industry.

The meeting of jobs and unemployed

Just consider the media excitement that occurred when, for once, the surveyed job vacancies (not the advertised vacancies) and the ABS “measure” of unemployment nearly equalled.

The Australian Financial Review reported a decline in job vacancies in June 2022, with the ABS unemployment rate falling to a new 48-year low of 3.4% in July:

‘For the first time on record in Australia’s history, there are more job openings than unemployed people to fill the vacant positions.’

Technically, the ABS’s May 2022 quarterly survey recorded 476,900. The AFR rounded this up to 480K, but it had fallen to 460,400 by August. However, unemployed people (seasonally adjusted) were 488,800 in July, which is technically higher than 480K vacancies. Fairly close if you don’t consider that surveyed jobs were falling and had been doing so for two months before the ABS came up with the 480K.

This had fallen to 460K job vacancies by the following month (see Figure 5). In July 2022, the ABS listed 90,600 gig employees as having no hours of labour and no compensation. The ABS considers these people to be “employed” despite no pay or work because they have “job attachments”. Jobseeker had a hard count of 892,066 people for whom they paid unemployment benefits.

But, “for the first time on record in Australia’s history…”, the ABS and Job Surveys numbers came somewhat close to one another, loosely speaking. The hullabaloo from the mainstream press was extraordinary. I so want to say FFS, but that would be unprofessional.

NON-numeric employment obstruction

Roy Morgan’s annual workforce numbers have been steadily increasing over the last 16 years. These figures show an average of 222,000 new individuals added per year. Because Australia’s population is concentrated along a 35,821-kilometer-long coastline, job searchers are unlikely to live in areas where there are suitable vacant positions.

When evaluating assertions of “labour scarcity”, it is essential to take a more comprehensive approach, taking into account the substantial rise in the number of individuals actively looking for employment, limited economic diversification and the decline of Australia’s secondary trophic economic level (manufacturing).

Factors exacerbating the scarcity of employment opportunities in Australia include:

- socio-demographic characteristics;

- geographical location;

- job suitability;

- employer discrimination;

- accessibility limitations;

- skill and education levels;

- competition;

- financial constraints;

- literacy levels;

- inadequate remuneration;

- restricted working hours;

- employer exploitation;

- job conditions;

- domestic violence;

- health concerns; and

- transportation issues.

The media and the Government have been hesitant to engage in a more detailed and nuanced debate on this topic. The media has issued propagandistic critiques asking that the unemployed “just get a job” or that “people lack the desire to work”. The unemployed are portrayed as intellectually and mentally inferior. Employers who exploit their employees and express irritation with the scarcity of susceptible individuals to fill low-wage temporary positions demonstrate a similar level of contempt.

Skill levels continue to be important in meeting future employment needs, but Australia’s policy decision to impose huge educational debts on young people in return for a degree may be viewed as a disheartening display of policy short-sightedness. A more pragmatic solution, akin to Gough Whitlam’s educational policies, could be to develop higher education programmes tailored to expected future demands (see Figure 6)

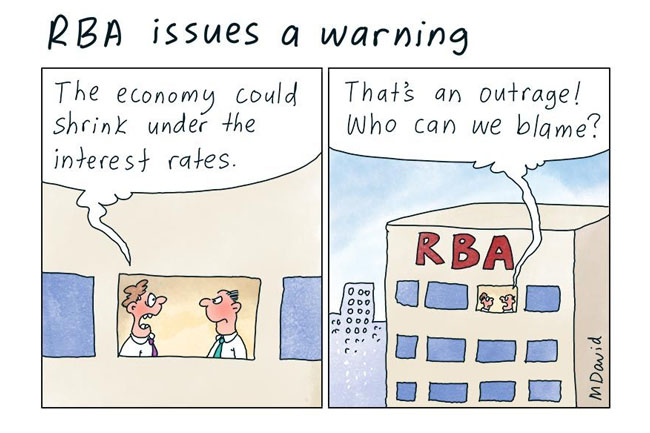

Long-term limits on actual employment development in Australia, as well as the persistent dissemination of misleading information claiming low unemployment figures, are all obstructions. Employers report difficulties in hiring candidates for roles that lack appeal at all skill levels. Unemployment, job markets, economic complexity, interest rate policies, corporate-driven inflation, income disparities, austerity measures without social support and educational demands must all be addressed in Australia’s economic future. Governments, the media and economists must address these difficulties head-on rather than hide behind the propaganda of flawed metrics.

John Haly is a freelance writer who manages a freelance business, Halyucinations Studios in Sydney.

Related Articles

- 1.5 million Aussies out of work and the immigration solution

- Joblessness: Another photo op, no follow up disaster

- Incompetence, not the pandemic, has wrecked the economy

- Conservative politicians and media pressuring 'lazy' youth into farm work

- Young workers worse off than ever

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.