There is a tsunami of poverty-related issues and draconian laws swamping offenders and filling prisons, yet we continue with the punitive penal estate despite its failure, writes Gerry Georgatos.

*CONTENT WARNING: This article discusses suicide

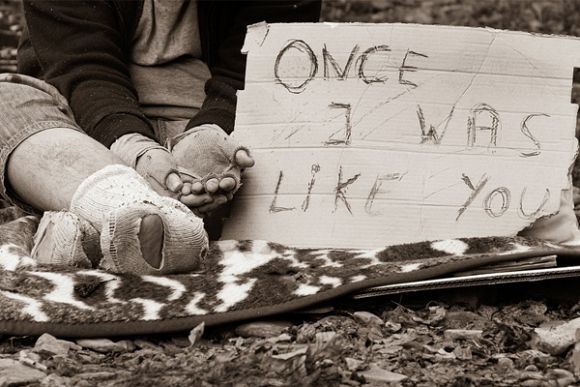

WE HAVE leaders for the haves. Where is the leadership for the have-nots? For those born into difference and disadvantage and unfairness. For those left behind.

In my last four decades, I have assisted tens of thousands of vulnerable souls, here and abroad. Ten tertiary qualifications, in three waves of education over three decades, did not educate me as well as did the coalface.

We leave people behind.

Nearly four decades ago, I commenced a decade of relentless global travel which opened my eyes to the horrendous lie of our generation — that we are lifting people out of poverty.

There is more measurable poverty among the human family than ever before, with both absolute and relative poverty guaranteed to accelerate. The horrendous lie of our generation is that poverty is being reduced around the world.

Eight of ten of the human family lives on less than USD$10 (AU$14.12) per day — one in two live on USD$5.50 daily (AU$7.76).

The World Bank sets the international poverty lines. In 2015, it revised them. Extreme poverty had been people living on USD$2.50 (AU$3.51). They revised it to USD$1.90 (AU$2.68). With this 60-cent reduction, suddenly, hundreds of millions of sisters and brothers were supposedly lifted from extreme poverty.

One of the world's richest economies, Australia, languishes one in five of its children under the age of five in poverty. Many are in abject poverty.

One Australian family brought me many sleepless nights. A family of eight children. Their mother died by suicide. Their father died the year prior. All the children were less than 17 years old; the youngest ones thereabouts with half-a-dozen years of life thus far. Orphans. Relatives took in a couple.

For recurring periods, four of the orphans would experience homelessness, five would be incarcerated in children’s prisons and one – from as young as 12 – was incarcerated 12 times in his 12th year of life alone.

One of the children, at 15, living homeless, took his life last year. A few years ago, two of the siblings walked off the streets into my – then – office. I housed them. Another reached out to me from interstate. I supported her. Nevertheless, I often think of the one I never met — the one who died by suicide.

How does a nation like Australia fail eight orphaned siblings?

We stigmatise the poor, the homeless, the incarcerated and their parents. We live with preposterous prejudices and criticisms of the poor. Difference, disadvantage and unfairness are often passed off by far too many as bad character. This leads to punishing the poor and the sick.

There is nothing as profoundly powerful as forgiveness. Forgiving others validates self-worth and builds bridges and positive futures. Forgiveness cultivated and understood keeps families and society solid as opposed to the corrosive anger that diminishes people, sending them into the darkest places, into effectively becoming mentally unwell.

Anger is a warning sign of becoming unwell. Love comes more naturally to the human heart; despite that, hate can take one over. In the battle between love and hate, one will choose love more easily when one understands the endless dark place that is hate and understands its corrosive impacts. Hate can never achieve what love so easily can. Hate and anger have filled our prisons with the mentally unwell, the most vulnerable and the poor.

I have worked to turn around the lives of as many people in gaol as I possibly could, but for every inmate or former inmate, whereby people like me dedicate time to improve their lot, ultimately there is a tsunami of poverty-related issues and draconian laws swamping offenders and filling prisons.

Gaoling the poorest and most vulnerable, the mentally unwell, in my experience, only serves to elevate the risk of reoffending, normalising disordered and broken lives and digging deeper divides between people — incarceration marginalises people. It has been my experience in general that people come out of prison worse than they went in.

We push maxims such as "violence breeds violence" and "hate breeds hate", yet we incarcerate and punish ceaselessly. Instead of carceral sentences working as some sort of deterrent, we have reoffending, arrest and gaoling rates increasing year in and year out.

One of society’s failures is the punitive criminal justice system and the concomitant penal estate. Despite the punitive penal estate having clearly failed society, we continue with it. For some, it has become easier to lie and act as if failure is a success.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, in The Brothers Karamazov, wrote:

'Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The person who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.'

We have lied for so long in this combative, meritocratic society that, for far too many, has ceased to love and to forgive. The psychological, emotional and spiritual well-being of others, of those most vulnerable, are lost to it. The mantra these days is the stricture of "self-responsibility".

Dostoevsky, who also authored Crime and Punishment and The House of the Dead, said: 'The degree of civilisation in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.'

Australia has doubled its prison population in the last 20 years with a disproportionate hit on the marginalised, particularly the descendants of the First Peoples of this continent.

But what are their crimes? Born into extreme disadvantage, abject poverty and into a spectrum with deplorable levels of likelihood of their deterioration from a state of hopelessness to becoming mentally unwell.

Socrates understood that "esteem" was imperative to the striving for justice and goodness. This is where we fail people — we are not there to build or rebuild their esteem, to strive lovingly. Socrates would have us believe evils are the result of the ignorance of good. Here, I am with Socrates — we have a society not bent on reinforcing the innate or reinforcing "good", but instead, we are a society that demands an impression of what good might be and punishes those who transgress.

We are after unilateral orderliness among all people, where justice argues itself as blind, where everyone is equal. But we are not equal.

Søren Kierkegaard argued sin meant wilfulness and unlike the Socratic view of ignorance of good, Kierkegaard was bent on the view that some people simply do not want to be good. As naive as I may appear, the Socratic view aligns with what I have seen in prisons — of people who want to be good, who are innately good, but who have accumulated despair, displaced anger and resentment from impoverished or disadvantaged upbringings.

The penal estate is not rehabilitative, nor restorative. The penal estate should have been an investiture in people rather than a dungeon, an abyss. The opportunity for healing, psychosocial empowerment, forgiveness, redemption, education skills and qualifications are continually bypassed. This madness never ceases to shock me.

Forgiveness is not an act of mercy but of empathy, compassion and virtue. According to vast bodies of research, forgiveness has many benefits, outstripping negatives and risks. Forgiveness strengthens families, communities and societies.

The most significant finding is the obvious — forgiveness makes us happier. The act of forgiveness improves the health of people and communities. It sustains relationships. Forgiveness builds and rebuilds lives, connecting people — and what better medium for this than through kindness.

It was Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the chairperson of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission who argued forgiveness as the only way forward to “true enduring peace”.

I note the Chinese proverb: 'It is better to light a small candle rather than curse the darkness.'

We have seen where we will be led when the only response to crime is punishment. The USA gaols nearly one per cent of its total population. Are so many so bad or is the USA extremely harsh on its most vulnerable?

One in four of the world’s prisoners are in American gaols. This is the future we need to avoid. If Australia would consider an amnesty – an immediate release – of very low-level offenders, more than 10,000 (a quarter of the incarcerated) could walk out of prison today.

If Australia were prepared to release those mentally unwell either into community care or other specialist care, again, many thousands would walk out of our gaols today. At all times we should be working closely, lovingly and forgivingly with those inside and so bring them out of the prison experience not worse but better.

As it stands now, there is an elevated risk of death by suicide, substance misusing and misadventure in the first-year post-release – up to ten times according to all the research. We do ever so little for people pre and post-release.

Society gains more from forgiveness, helping and empowering people than from any other measure. This is not to suggest some crimes should not require imprisonment, but all people are capable of redemption and salvation. There are far too many who should be supported instead of gaoled.

People who can be supported are more likely to be good without having to go to prison. If you believe in people for long enough, they will believe in themselves.

For those who are sentenced to prison, these must be places where people come first, not last. And there must be forgiveness. Prisoners must be assisted in every way to forgive themselves. As a society, our focus must be on redemption. The most powerful kick-start is a society – a justice system – that is forgiving and hence promotes a message of love for everyone. For far too many people, repentance without forgiveness is torturous.

For many, forgiveness is a radical, gratuitous proposition. We need to change this. Understanding difference and unfairness is the first step — this is lighting the candle instead of cursing the darkness.

If you would like to speak to someone about suicide you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus. He is the national coordinator of the National Suicide Prevention & Trauma Recovery Project (NSPTRP). You can follow Gerry on Twitter @GerryGeorgatos.

Related Articles

- Incarceration: How Australia fails its vulnerable

- Children in prison deserve proper healthcare

- Changing the lives of Australia's incarcerated Indigenous people

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.