There have been more suicides so far in 2019 than this time last year.

But the Commonwealth and the states talk but do little. As of the first day of August, I estimate that 1,700 Australians have been lost to suicide, more than this time last year.

But as of August, it is certain that more than 100 individuals of First Nations heritage have been lost to suicide — more than this time last year.

The Commonwealth Government has promised a lot but is delivering nowhere near enough to reduce the suicide tolls.

Nearly one-third of the Australian suicide toll is of the migrant-born, the majority who live socioeconomic stressors and disadvantages. Nearly two-thirds of all Australian suicides are socioeconomically narrated.

For First Nations peoples, the poverty narrative is tragically much more pronounced, with nearly all the suicides of individuals who lived below the poverty line.

There’s a lot of posturing by far too many on the suicides crisis and a lot of institutions, departments and services being seen to be doing something but little interface with the people at-risk.

There are many suicide prevention badged organisations but few of them sponsor outreach to the critically vulnerable and few engage with the at-risk. The majority are information services, information gathering organisations, research institutes and the like but consume the majority of “suicide prevention” funding.

There are noble organisations and services, but they are few.

The carpetbaggers line a country mile for funding

Governments – State, Territory, Commonwealth – deliver at best piecemeal, minimalist responses, leaving those at the coalface of the crisis frustrated.

The same old who have long failed to deliver get funded. Yes, there is a "mental health" and "suicide prevention" elite who lobby for funding for their inner circle and the majority of funding is subsumed in research and data collection. But the majority of funding is used up by the research bureaucracy, with little or no flow-on effect to those they rarely or never engage with the at-risk.

The First Nations struggle

First Nations suicide prevention needs a billion dollars investment. If this is facilitated suicides can be reduced substantially — bringing some semblance of parity between non-Indigenous and First Nations suicide rates.

There is the possibility that by year’s end that First Nations suicides will for the first time exceed 200 suicides.

Victoria has few suicides each year of First Nations people. But thus far this year, Victoria has already exceeded all of last year’s 12 suicides.

Townsville alone accounts thus far this year, 9 suicides of First Nations peoples.

The small Kimberley community of Balgo – with a population of a few hundred – has suffered three suicides of young people in the last few months.

It is wrongly presumed that there were higher rates of suicides of First Nations Australians in the mid to late 1990s. That’s a poor research analysis. The suicide toll, each year of the 1990s averaged less than 100 per year.

The average over the last few years is 160 per year.

However, in some of the years of the 1990s, the suicide rate was higher than present. But the then total First Nations population was considerably less than today.

Since then, with every Census the First Nations population has grown, by hundreds of thousands each Census, with more people identifying proudly. But the majority of those finally identifying were not living below the poverty line. This skewed the data, reduced the suicide rate and the poverty narrative lost a little but when you disaggregate socioeconomically you find that nearly everyone lost to suicide lived below the poverty line.

Prevention strategy

Australia’s suicide prevention plans remain misdirected and lack much-needed focus on early intervention, assertive outreach, intense psychosocial and long-haul support.

Merely raising awareness of suicide and potential tipping points is not suicide prevention. Early intervention means preventing people from reaching the disordered thinking that is suicidal ideation, which culminates in toxic internalised grief, a negative psychosocial self, aberrant behaviour and ultimately a suicide attempt.

Australia’s current focus is much further down the spiral than ideation. Too often, interventions take place so late in the piece that they have little chance of making a difference.

Any argument that there have been substantial investments by governments into suicide prevention is a false narrative. Money is being directed to perpetual research, with little of what is recommended going on to influence policy.

The investments are forever in the being-seen-to-be-doing-something basket, such as research, roundtables, trial sites, awareness and reductionist education campaigns — all which are relatively cheap to fund.

The suicide prevention trial sites are a misspend — an exercise to "integrate" existing services in the health and allied health spaces and to squeeze more out of underfunded and overstretched services.

Where’s the focus on outreach? The seriously at-risk will never walk into any support service. Where are the calls for more specialist personnel, community care psychosocial support facilities, resourced home-based systems? People need people, both during critical periods and in long-haul throughcare.

As a nation we lay claim to responding to the suicide crisis. We are one of only 28 nations with a "suicide prevention plan". But the plan is paper-thin. It’s about encouraging services to work collaboratively in suicide prevention and postvention, and that is the least of what should be done.

Our suicide rate: Who is most affected?

Australia’s suicide rate today is equal to 2015 as the highest it has been in ten years. To reduce suicide, we must reduce not only the number of attempted suicides, but also the hospital admission rate for self-harm, the rate of domestic violence, the prevalence of bullying, and the least discussed tragedy in the nation – child sexual abuse. We also can’t ignore the -isms: racism, sexism, ableism, and classism.

We need to reach elevated suicide risk groups with tailor-made support. Individuals removed as children from their families are at highest risk.

Just as high-risk are individuals released from prison; they are at elevated risk to suicide or unnatural death in the weeks and months following release. Also, at elevated risk are the homeless, followed closely by members of families that have been recently evicted from public rental housing.

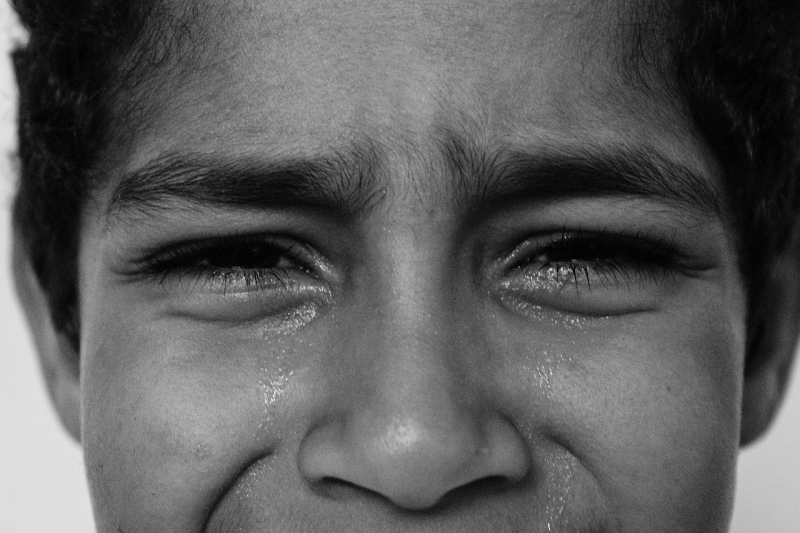

Child suicides are no longer rare — rates are the highest they have ever been.

Annually, more than 40,000 children between 12 and 17 years of age are estimated to have made a suicide attempt. One-quarter of 16-year-old females self-harm.

Suicide takes more First Nations children, as well as migrant children from non-English speaking cultural backgrounds than it does others. First Nations suicides comprise seven per cent of Australia’s total child population, and yet a shocking 80 per cent of Australia’s child suicides aged 12 years and under are of First Nations children.

Migrant children are also often neglected in suicide prevention discourse. They are at an elevated risk primarily because of racism, and the perception that they must ‘fit in’. This can lead to disordered thinking, internalised conflict, shame, and diminution of the self.

The National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan 2017 to 2022 is fixated on the provision of support by self-referral, effective at the near-death experience. Improving life circumstances and early intervention approaches must be the focus. As a nation, we have not prioritised this harrowing crisis.

Suicide is the 14th leading death cause of death globally but over three-quarters of suicides occur in low-income and middle-income countries. The other quarter, in high-income nations, more than two-thirds of the suicides are of people living below or in proximity to the poverty line.

Similarly, the majority of Australia’s domestic violence deaths are not found in the high income or wealthiest suburbs but within low socioeconomic postcodes, in the poorest suburbs and towns. The majority of domestic violence deaths are of people living below the poverty line.

Researcher and psychologist Jason Bantjes described 'suicide as a serious public health problem in low- and middle-income countries'. He is not the first. Bantjes and colleagues have looked at understanding the context for non-fatal suicidal behaviour in order to cornerstone 'public health interventions to reduce suicide'. He argued that poverty and symptoms of depression 'are well-established risk factors for suicidal behaviour'.

Mental health expert Jutta Lindert at the 8th European Public Health Forum reported that low-income countries in Asia and the Pacific and in Eastern Europe have among the world’s highest burden of suicide. Lindert associated suicides with “psychopathologies such as depression and hopelessness". Lindert reported that “poverty, scarcity and economic crisis are associated with psychopathologies".

Last year’s Raising Canada report included child poverty as one of the main drivers of Canada’s 'high infant mortality and suicide rates'.

The report stated:

'Suicide is the second leading cause of death for young people in Canada, behind accidents.'

The report found that 20 per cent of Canada’s children "live in poverty" and '1.2 million children live in low-income housing'.

The report also found that sexual abuse was more pronounced below the poverty line but as a whole ten per cent of children experienced sexual abuse.

The report argued that:

'Poverty and abuse create toxic stress for children that affects their well-being today.'

In February, the Western Australian Coroner reported on 13 child suicides in the State’s Kimberley and found that they were shaped “by the crushing effect of intergenerational trauma and poverty". The children were aged between 10 and 13. Pronounced negative factors that are more common within poverty were found — alcohol abuse, domestic violence, sexual abuse.

Crisis support services can be reached 24 hours a day: Lifeline 13 11 14; Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467; Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800; MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78; Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636.

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher. He is also the national coordinator of the National Suicide Prevention & Trauma Recovery Project. You can follow Gerry on Twitter @GerryGeorgatos.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.