What happens when you uncover clear proof of a Russian identity theft and dating scam? Unfortunately, in Australia, not much it seems.

LIKE MANY single Australian men, I was considering my options for a life partner. Some friends had recently hooked up online and so I was discussing the facts with a mutual friend. She told me her father, an Englishman, had met a Russian woman online and they were now happily married. Apparently, she over-fed him, so he was getting fat and he'd changed his business style to accommodate his new status. All this sounded attractive — with only one reservation: I did not know any Russian women.

Next time I was online, all these 40-something women were popping up showing interest in me. Curiosity got the better of me and I answered one. The photo was of an attractive blonde woman, although I noticed the photo attached to two slightly different names — perhaps not so unusual in someone sticking their neck out, advertising their life interests. I sent a free message and the answer came back with an off-site email address.

The longer we emailed, the more romantic her word descriptions became. I thought to myself: she is definitely not Australian, she hasn’t raised money yet.

My friend had said her father went to Russia, so I brought this up. Pretty soon, she was going on holidays and would come to Australia. She reportedly organised flights and visas and so on, at a cost of the equivalent to $1,900. I did not ask if she had the money, but soon the idea I would pay for these emerged. Having been scammed by a major Australian bank, I saw the same system emerging. There was a mistake in the accounting and I would be responsible for the funds, even though she had made the mistake. She would demand more funding, and again, and then ultimately demand more until I was devoid of cash and assets. Then move on to the next customer.

I decided to do some checking. After all, asking the authorities to believe my story was like asking a judge to believe the bank scammed its clients (as a lawyer, the judge would have been busy finding how the customer was bad and the bank was a victim of his circumstances). I could see myself pushing snow uphill with a (forky) stick.

Eventually, a Visa card address arrived for the funds to transfer. After checking, I found it was a special part of the Bank of Moscow and that the minimum deposit was $2,000 equivalent. Knowing Visa deposits can be extracted worldwide I considered where this person could be and why the deposit was acceptable under $2,000. I then questioned why I should need to have a bank account to pay the funds on an international transfer. It came to be another person’s name in another Moscow-addressed bank.

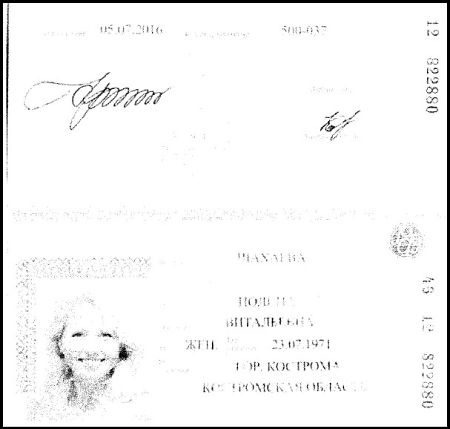

This was definitely sounding like an Australian bank scam, where funds were transferred between accounts without the customer’s agreement and knowledge. Only here, it was to pay for the plane fares and passports and so on. However, I had already been given a purported passport document. This required an explanation, because I had been told my romantic friend had never been outside of Russia. The passport was to her purported name and address.

I had asked for an official photograph and, to identify a place on one photo where the light came through a window, for the shape of the window. The reply came that it been taken at a friend’s place.

I then started checking more of the 20 or so photos that had come with the emails. With the cursor over the top they showed a Jpeg number. But one under the cursor showed the legs cut-off, with my romantic friend standing in snow in bare feet on skis with snow boots beside her. I questioned the image and was told 'she had cut my legs off in the photo', which was not quite good enough.

I was then convinced the photos may be someone else. I had received some photos of a different style that may have been official. I checked these against official photos available and one came up with a different name and city. I checked the address and it blared: Go to Facebook.

I did that and there was the photo.

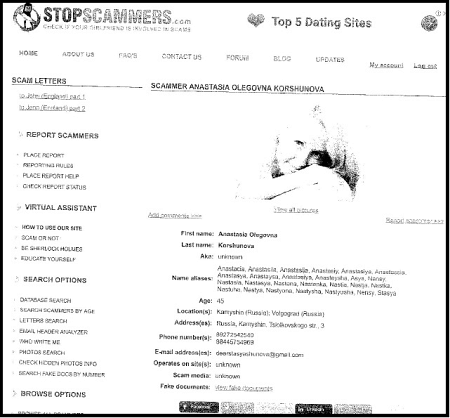

I had a new name to the photos and here were most of the ones I had received. I didn’t explore the site fully — I had enough to satisfy me. I contacted my romantic friend and was told the woman on Facebook had stolen her identity to make money from it. This was definitely a parallel with Australian bank scams: when faced with the truth always blame the other party, but never admit liability. I then checked further and found my romantic friend had advertised in the United States. I went further and joined a Russian scammers' identification site and found another name to the photo advertised in England, with an explanation from a man who had borrowed £8,000 for housing finance to clear his romantic friend’s mortgage and then was asked to find more money for an injured daughter’s operations. He refused, and published the name and photo as a scammer.

The Facebook person was not the scammer — too many facts were different. I once again emailed the Facebook person with the stolen identity and told her of her plight, as I would like someone to do with me. To this day, I have not heard from her, but consider she is just as much a victim as those defrauded of their money.

I now had the whole scam covered and so, with proof, contacted Interpol. They said I would have to go through Australian police. I contacted the Australian Federal Police and they said contact Queensland Police. I rang the Police in Brisbane, but they said to contact my local Police station.

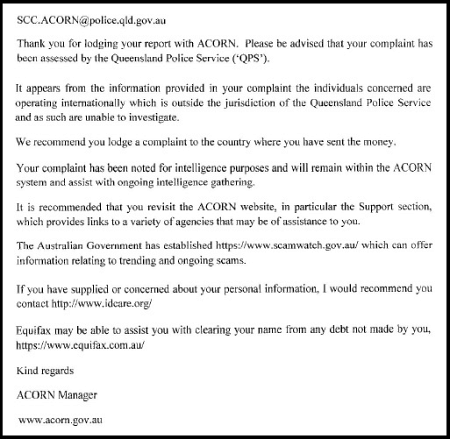

The lady on duty was understanding and could see that a bit of co-operation between police forces and these scammers of at least three English-speaking countries would be out of business. With her help, we reported the facts to ACORN (the Australian Cybercrime Online Reporting Network). Eventually, I received a number and advice to report the matter to Scamwatch (a resource run by the ACCC), and any further material to submit to ACORN for attaching to the same file.

A few days after that, I received a letter saying that, because the matter involved Russia, Queensland Police could not be involved because of jurisdiction and that my money was lost. The investigator did not even realise I had not paid any money, but the scammers had given me their money receiving account details.

However, the Commonwealth Criminal Code 1995 has a section on when cybercrime is regarded as being an Australian offence and that, to me, covered my situation. So I rang the Russian embassy, but the person on the end of the phone hung up one me before I got past "Perhaps..."

This meant I had to use my rudimentary computer skills and Google Translate to locate the Russian Police (Politsiya). I anxiously typed in 'Russian cybercrime' and up popped a 6 June 2017 article by John Leyden in The Register, 'Russia is struggling to keep its cybercrime groups on a tight leash'.

Russia is struggling to keep its cybercrime groups on a tight leash - Cybereason Intelligence Review @TheRegister https://t.co/SNExTOfaCN pic.twitter.com/uMIYfU4xDL

— Cybereason (@cybereason) June 7, 2017

If this is the case, why can’t Australia work with Russia under the circumstances identified? It appears Russia is turning a blind eye to cybercrime provided it does not involve Russian citizens. The Commonwealth Criminal Code identifies a crime outside of Australia is committed under the Code if it is a crime in the foreign country — but what happens when the scammer's country turns a blind eye to the plight of Australians?

In the interests of Australia because these condoned hackers and scammers are also able to target Australian Defence and Defence Industries without fear, an agreement to cover cybercrime prosecution is necessary. Further, with Australia and Russia competing more and more in world agricultural markets, inside commercial information to Russian negotiators is more than important.

If the problem with scammers misusing Australian citizens in personal money scams is not enough and is not stopped at the gate by ACORN, then it may be time to consider stopping scammers through controlling the content allowed by internet providers.

Top #secret #information about #Australia’s #military #hacked https://t.co/NSgQzNBei6 #security #defence #topsecret #ADF #RAAF #RAN #notgood

— Madhu Alasyam (@alasyam) October 11, 2017

NOTE: The name of the author has been concealed for obvious reasons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

The future in the war against #cybercrime — machine learning and #AI https://t.co/Wvq6KDAPIS

— IndependentAustralia (@independentaus) October 13, 2017

Expose the fraudsters. Subscribe to IA.