Imprisonment and punishment do not lead to more harmonious and prosperous societies, writes Gerry Georgatos.

IF YOU GIVE OUT love, you get love back. If you give out hate, you incur hate. Hate breeds anger, venom, confrontations and grief. Until the past can be done away with, there can be no brand-new day.

Many say not everyone can be forgiven. Many say not everyone can become a redemptorist. Some say there are those who are too far gone. But who is anyone to judge otherwise?

In my view, the most wicked criminality – even depravity – should not exclude hope and deny people redemption and salvation.

If the courts and parole boards extinguish all hope from an individual, they condemn them not only indefinitely to a jail cell, but also as the walking dead. No one is beyond redemption.

The Netherlands Government and their justice system have gone the way of love, understanding and forgiveness. As a beacon of enlightenment, they are rapidly closing prisons.

Yes, they have transformed the penal estate to one of restoration, transformation, specialist supports, love and nurture. The Dutch recognised a significant proportion of those once corralled in prisons were people with mental illnesses or psychosocial disabilities.

A history of psychosis should not mean a long carceral sentence. It should mean addressing the psychosis. Is there any greater legacy than turning a life around?

Adequately resourced community care programs with specialist support in the Netherlands have seen people with mental illnesses who would have been incarcerated, instead treated. This not only is salvation but prevents another crime. Authentic substantive outreach is a crucial imperative.

Society is kindest when it supports vulnerable people and treats people with severe personality disorders, dissociative disorders, addictions and trauma. Society is cruel when it imprisons the sick. Let us remind ourselves, that any human being can become sick and mentally unwell.

I have worked with people who have committed some of the most heinous crimes. I was able to turn them around to their best selves. Is this not what we should want?

The humane Dutch approach led to a reduction of prisons over decades.

Australia has 115 adult prisons, 18 in Western Australia. Australia has 17 children’s prisons.

Sentences are still imposed, but tailored support is provided in the effort to improve the individual.

In Australia, the demonisation of an offender can be a brutal public spectacle, a horror show where the criminal justice system and the media often depict offenders as irreparable "evil monsters".

The Netherlands justice system works redemptively with people who commit serious crimes. In general, serious crime offenders are at high risk of recidivism. The Dutch courts place them in humane institutions, secure settings, where they are supported – and programs work specifically to their successful reintegration into society.

At last count, the Netherlands has 1,300 serious offenders in these institutions treating the psychological conditions of the individuals as opposed to the invalidations and impure blame culture of a prison.

The Dutch also recognise the fact that the majority of criminal offending is by "have-nots", as is the case in every country. In Australia, near-all of the prison population is from the lowest quintile of income-base.

In my experience, few people are so unwell that they can’t be helped. If you believe in someone, relentlessly, they will believe.

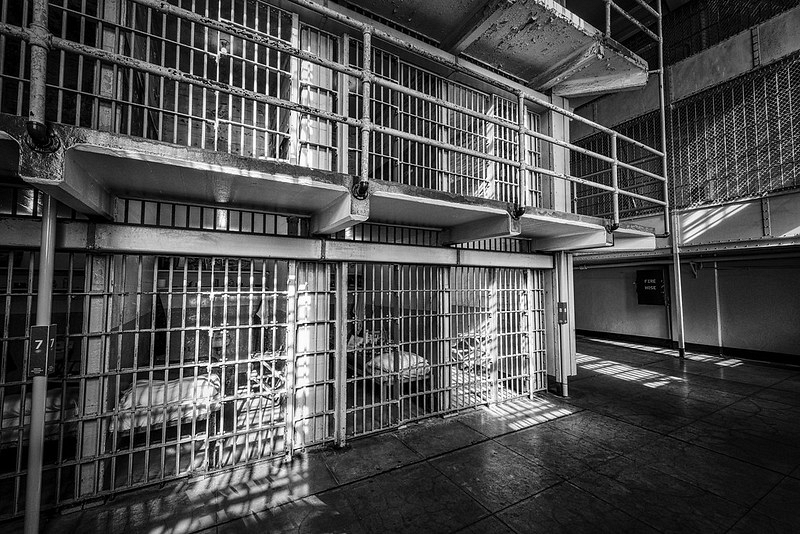

The insides of the Australian prisons, including Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre, mistreat the incarcerated as if they are less than nothing. It breaks the heart.

We may never get peace on earth. We will never get perfect societies. However, we can achieve better and kinder societies.

We should also desist with scaring society with outlier horror crimes and stop the calls for tough-on-crime laws, such as universal mandatory sentencing prescriptions and sweeping high-risk offender laws. Let us spare the rod.

I have been robbed several times. On two occasions I walked in on the attempted burglaries. I did not call the police. I don’t recommend this, but in my case, we chatted. We shook hands before they left. I’d rather give someone the opportunity at redemption than a carceral sentence. One of them, I have assisted many times, since again meeting him as a street-homeless individual.

It is not just the Netherlands. Sweden is renowned for Europe’s lowest re-offending rate. The Swedes focus on transforming the lives of the sentenced. Penance is not coupled with relentless blame and further punishments. Penance is coupled with opportunities at improving oneself. Swedish prisons have been closing for years.

Swedish prisons focus on rehabilitation. Swedish prisons are not about crime and punishment. They are about restoration and reintegration.

We call this ‘progressive’ but I call it ‘right-minded.’

Swedish prisons focus on developing a person's transferable skills. University courses, apprenticeships, a wide variety of learning, which will make the individual employable. They may come into prison without an employment history but leave with a job lined up. It is my general experience that people released from Australian prisons come out worse than when they went in. With the Swedes, it’s the other way around.

Norway’s island prison, Bastoy, has few guards. Prisoners self-manage their daily affairs and routine. There are no locks on their doors. This is all a product of the culture: humaneness.

A former prison, near Haarlem in the Netherlands, has been converted into a multi-purpose student accommodation village and social housing fraternity.

We must shift the public consciousness: that framing tough-on-people narratives will reduce crimes. The truth is it doesn’t work. Simply being punitive doesn’t work. It makes everything worse.

Decriminalisation of soft crimes are a must-do.

I also mentor many to understand life is brief and to live within their means, but live a full life that respects human life and gives people a second chance.

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus. He is the national coordinator of the National Suicide Prevention & Trauma Recovery Project (NSPTRP). You can follow Gerry on Twitter @GerryGeorgatos.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.