Against Britain's background of Islamophobia, King Charles III could usher in a more tolerant era for Muslims, writes Bilal Cleland.

THIS YEAR, we witnessed the beginning of the reign of Charles III who has been described as an Islamophile, a friend of Islam.

Australia has been content to accept the British constitutional monarch as head of state until now, but the new Federal Government has already appointed a Minister for the Republic. We can expect another referendum in the second term of this Government and it is likely to pass.

We can look back on the history of the British Monarchy as an interesting chapter in history but it is time for this country to come out of the colonial cocoon.

Since the succession to the Monarchy of Charles I in 1625, the first King of England to bear the name, much has changed.

The congregation in the London Central Mosque welcomed Charles III with prayers and the singing of ‘God Save the King’.

There would not have been such joy in 1625 if there had been any public Muslims in England at that time.

This was the time of politically uncontested divine right monarchy, the assumption that the king was responsible only to God Almighty for his actions, not the people he ruled.

The notion that the sovereign was the source of all law, that the king could do no wrong, was generally accepted political reality across Catholic Europe in the 1500s and 1600s.

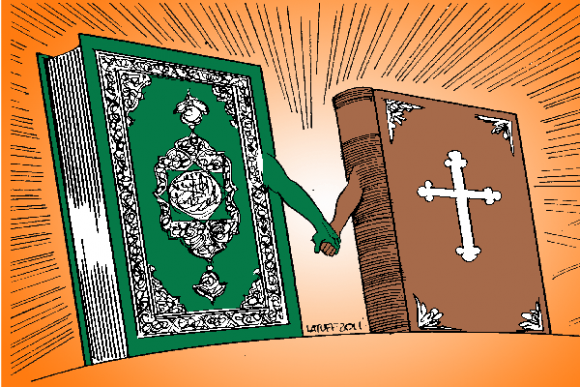

This new Charles III, content to be a constitutional monarch, said in the 1990s that he wished to be the defender of faiths, a change in the title first awarded to Henry VIII as Defender of The Faith.

Under Charles I, the theory of divine right was seen by some Anglicans and most non-conformists, Protestants outside the Anglican Church, as essentially a Roman Catholic policy.

Opponents of the king took up arms in 1642 in the Civil War, causing some 600,000 deaths from fighting and associated disease.

One of the major reasons divine right was fought so strongly by Protestants was that it was identified with tyrannical government.

On 30 January 1649, King Charles was beheaded for his crimes against the people.

From 1649 to 1660, England and Wales, then Ireland and Scotland, were ruled as a republic under the Parliament and a Council of State.

The return of the King, 1660

The Protectorate Parliament was dissolved in 1659 and military leaders recalled the Rump Parliament in 1660 which brought back King Charles II.

The constitutional reforms were eradicated and opposition to Charles I was forgiven, except for those who had signed his death warrant. They were hunted down and when caught, were hanged until unconscious, revived, disembowelled while awake then cut into four pieces for public display.

The grand old cause of parliament against the king however was not forgotten and would surface once more in 1688 in the Glorious Revolution and the beginning of the modern constitutional monarchy.

Where was Islam?

What is left out of this well-known account of the upheavals of this Carolingian Era is the role of Islam.

According to Humberto Garcia in Islam and the English Enlightenment 1670-1840:

‘From the late 17th to the mid-19th Century, Islamic republicanism captivated the radical Anglo-Protestant imagination and redefined reformed orthodoxy in England, North America and the transatlantic world, only to be silenced by the anti-Islamic sentiment that gripped Victorian culture after the 1857 Indian Mutiny.’

One of those radical Protestants was Henry Stubbe, who according to Garcia argued:

‘He (Muhammad) was a virtuous republican who promoted the seven Noahetic precepts, the Mosaic law, and Christ’s word. Stubbe’s account offers a reassuring message for English nonconformists: in an age dominated by Trinitarian persecution, only Islam’s tolerant principles can guarantee a constitutional republicanism that would allow them to become citizens equally entitled to rights, property and privilege.’

Stubbe's work, The Originall and Progress of Mahometanism, first published (handwritten and rare for reasons of preservation of his life) in the early 1670s, was influential.

It circulated privately for over a century and Garcia attributes to this work the 1600s civic republicanism transformation into early 1700s radical Whiggism.

This political strain of thought laid down the basis of modern British constitutional thought.

Resistance to intolerance and divine right rule

Two great cataclysmic events occurred at the same time, one in Hungary and the other in England, both linked to Islamic thinking.

Resistance to the Catholic Hapsburgs in Hungary and resistance to the Catholic Monarch, James II, in England became associated in the Tory mind.

The marriage of James, Duke of York and heir to the throne, to a Roman Catholic ignited the Exclusion Crisis. As this crisis developed, a joint Ottoman-Hungarian campaign led by Count Teckeley was launched against Catholic Vienna [Garcia p.33].

Henry Stubbe’s imprisonment for his criticism of the Duke of York shows he was in the mainstream of those denounced as “Protestant Mohametans”.

Garcia wrote:

‘By the 1680s, Count Teckeley had become a menacing figure for orthodox Christians who associated his tolerationist politics with the attempt to supplement Christendom with Islamic rule. To combat the counterreformation, Teckely accepted Ottoman-Islamic law in order to protect Protestant Hungary’s constitutional right to free worship, clerical independence, and national sovereignty.’

Tory propaganda reached modern War on Terror proportions. It denounced the promotion of religious toleration as a cover for an international Muslim-Protestant plot to destroy Christendom.

Tories in England claimed: ‘that radical Whigs are accomplices in a Hungarian conspiracy against church and state, exposing the constitutional principle of a limited Protestant monarchy as founded on Islamic innovation rather than Christian tradition.’ [Garcia p.51]

They portrayed the Treaty of Karlowitz 1699 and the defeat of the Ottomans and their Hungarian allies as divine retribution against the infidels, both Muslims and Protestants.

However, Garcia argues that the 1688 “Whig Triumph”, the Glorious Revolution and the beginning of the constitutional monarchy were Islamic-inspired events that prevented the counterreformation with its inquisition from spreading into England.

The Protestant Mahometans, the supporters of religious toleration and those who demanded that the monarch should be subject to the rule of law, eventually won the battle for the future.

Bilal Cleland is a retired secondary teacher and was Secretary of the Islamic Council of Victoria, Chairman of the Muslim Welfare Board Victoria and Secretary of the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils. You can follow Bilal on Twitter @BilalCleland.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.