Haemochromatosis is the most common genetic disorder in Australia. Untreated, it's fatal. Yet it's the most underdiagnosed deadly disease of all. Sufferer David Donovan urges the Government to act now and save countless lives.

THERE IS a deadly genetic disorder running rampant throughout our society. It affects about one in every 200 Australians ─ and a much higher proportion of certain groups. One in seven Australians are carriers of the gene that causes this condition.

If diagnosed early enough, it can be fully and easily treated without drugs or surgical intervention. Untreated, it is potentially fatal. Yet it is probably the most underdiagnosed deadly disease of them all. And the public is mostly ignorant of the condition.

A simple blood test can tell you if you have it, yet successive federal governments have refused to conduct population testing, or even conduct meaningful public information campaigns.

The condition is hereditary haemochromatosis (HH), also known as inherited iron overload disorder. I have it and you might too.

What is haemochromatosis?

Haemochromatosis is a disorder where too much iron builds up in the body (iron overload).

In the intestines of healthy people, an adequate amount of iron is absorbed from the foods they eat; the excess is excreted.

But for those with haemochromatosis, the body absorbs too much and has no way to get rid of it. So it stores the excess iron in your joints and organs like your liver, heart, and pancreas. This damages them. If it’s not treated, haemochromatosis can make your organs stop working and cause premature death.

There are two types of haemochromatosis: Type One (hereditary) and Type Two (non-hereditary). About 83 per cent of people with the condition have the hereditary form. If you have two copies of the genes that cause it – one from your mother and one from your father – then you are at grave risk of developing the iron overload disorder.

Because of its tendency to darken the skin, HH is sometimes known as "bronze diabetes". And since it is over-represented among Irish and Nordic people, it is often called the Celtic Curse and the Viking Disease.

Dave’s Story 1: The luck of the Irish? Lucky for some...

I found out I had haemochromatosis a little over ten years ago, just after I’d turned 42. It was pure chance.

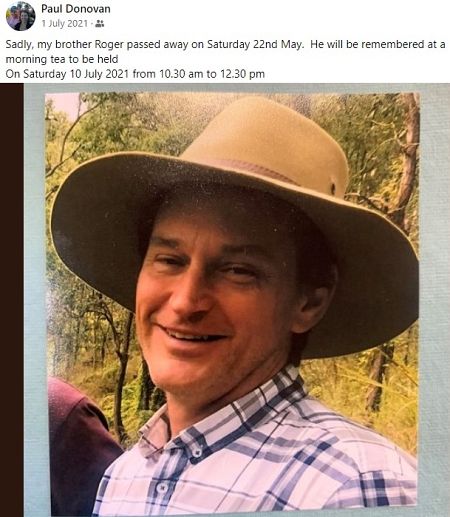

My cousin Roger was diagnosed with bowel cancer, a disease which can be hereditary. My caring mother suggested all her children get tested to see if they had signs of this disease. Roger was born about eight years before me.

The Government screens the entire population for bowel cancer when they turn 50, which may have resulted in Roger’s diagnosis. As you know, survival rates for all cancers rapidly increase the earlier they are diagnosed.

So, despite feeling fighting fit at 40 odd, I took Mum’s timely advice and went to the doctor for a check-up. It was lucky I did. Thanks, Mum!

Sadly, Roger was not so lucky. Despite the Government’s nationwide bowel testing initiative, it was too late for him. After a valiant struggle, he died from his illness last year. He was just 59.

How do you find out if you have HH?

Hereditary haemochromatosis is diagnosed by a simple genetic blood test. Generally, doctors only order the tests if your symptoms suggest haemochromatosis, or if you make them aware a close relative has been diagnosed with the condition. The symptoms do not usually emerge until you are around 40 and begin as mere tiredness or slight joint aches — symptoms often simply attributed to signs of ageing. This means the disease is seldom diagnosed early enough — if it is at all.

Unlike bowel cancer – and despite being the most under-diagnosed deadly disease in the nation – there is no nationwide testing initiative for haemochromatosis. Nor is there any significant official government information campaign to inform the general public about the disease, or even for those most at risk.

Dave’s Story 2: The diagnosis

At my request, after my cousin’s diagnosis, my GP agreed to test me for bowel cancer. The national government test for bowel cancer for 50-year-olds simply involves sending a stool sample away to a pathologist.

In addition – and not part of the official testing regime – my GP also asked for a simple blood test.

When the results came back, the stool sample showed no signs of bowel cancer. The blood test, however, indicated I had a dangerously high liver enzyme count.

A further iron study showed I had a stratospheric 1747 nanograms (ng) of ferritin (protein iron) per millilitre of blood. The normal range is between 20 to 250 ng/mL.

Finally, my exact condition was confirmed when a subsequent genetic test revealed I had both sets of the genes required for the hereditary disorder.

It was the first time I had ever heard of iron overload disorder.

What is iron overload disorder?

Iron overload disorder is a slowly creeping disease, the symptoms of which do not begin until a person reaches their 30s, 40s or even 50s. It kills by causing secondary complications, such as cancer and organ failure.

As excess iron slowly leeches from the gastrointestinal tract, it is incorporated into tissues and organs. If the iron levels in those tissues get high enough, the individual may develop haemochromatosis.

Common complications of untreated haemochromatosis include liver failure, liver cirrhosis, heart failure, arrhythmia, kidney failure, spleen failure, stomach cancer, diabetes, skin bronzing and general organ damage.

Dave’s Story 3: Rusting out from the inside

After my diagnosis, my doctor referred me to a haematologist, or blood specialist.

This expert physician told me that the symptoms normally don’t emerge until between the ages of 40 and 50. And even during those times, they are generally nothing more than a general lethargy and perhaps soreness in the joints ─ easy to ascribe to just “getting old”.

I didn’t even have those, just a chance blood test led to my diagnosis.

My haematologist said that, even though I didn’t know it at the time, I was “slowly rusting out from the inside”.

Are you at risk?

Haemochromatosis is the most common genetic disorder in the Western world. In Australia, it is estimated that one in every 200 people has the condition.

Men have 24 times the risk of developing full-blown iron overload compared to women.

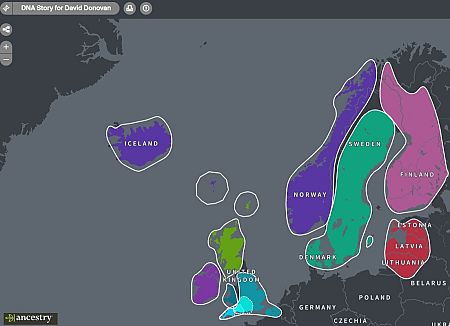

But if you happen to have Nordic, Norman or Celtic ancestry, your chances of having HH are estimated to be more than 1 per cent. One in every five people of Irish descent carries at least one of the genes that produce the disorder.

Dave’s Story 4: The Celtic Curse or the Viking Disease?

Before I began treatment, I began to look into how I came to have the genes that made an “Iron Man”.

I discovered that there are two schools of thought about how it emerged. The Irish claim the disease as their own, the Celtic Curse, as there is a higher prevalence of the condition there than in any other nation on Earth.

But other research supports the Viking hypothesis. Studies and surveys showed that the main clusters of people with the disease were in areas that were dominated by Norse − and later Norman − invaders from about 700 AD to 1100 AD. Ireland was one of the most pillaged places, although Wales, Scotland and the northern UK didn’t fare much better.

What is not in dispute is that in the chilly and damp environments of Northern Europe during the dark ages, more iron in the diet would have helped keep the body temperature stable. Moreover, in times of want and hunger, the genetic mutation may have aided those with a lack of sufficient iron intake.

I have a native Norwegian great-grandfather, a German great-grandmother and a Devonish grandmother. My name is Irish. A recent ancestry.com saliva DNA test further shows just how Viking I am.

The good news: Treatment is a prick

The most commonly used treatment for haemochromatosis is removing some of your blood, usually about 500 or 600ml at a time. This procedure is known as phlebotomy or venesection and follows the same pattern as giving blood.

The removed blood reduces the number of red blood cells that contain iron, causing your body to use more iron to replace them. This process reduces the amount of iron in your body.

There are two stages of the treatment.

Firstly, the induction phase, where blood is removed on a frequent basis (usually weekly) until your iron levels are normal. This can sometimes take up to a year or more.

Then ongoing maintenance, where blood is removed less often (usually two to four times a year) to keep your iron levels under control. This is usually needed for the rest of your life.

More good news: if you are diagnosed with haemochromatosis early, before significant organ damage occurs, and keep your iron levels within the normal range, there is generally no decrease in life expectancy.

Dave’s Story 5: Treatment and management

The specialist told me to lay off the booze and red meat for a while and set me on a course of weekly venesections. These were initially carried out at an oncology clinic in a local hospital. It was an interesting experience. Not only did they remove my blood, but they also replaced these fluids in the other arm at the same time with the aid of a saline drip. Considerate!

My liver and iron count rapidly improved and a little over a year later, I was able to start donating fortnightly at the local Red Cross blood bank. The Red Cross will not allow you to donate more frequently than every fortnight, although they do like the iron-rich blood!

Later, the venesections went to being monthly, then every two months. These days, I donate blood every three months, just like a regular donor to the Red Cross. I rarely gave blood before my diagnosis but now, I really look forward to seeing the pleasant people at the Ferry Road blood bank, not to mention their tasty snacks!

Why is there no population screening for HH?

Haemochromatosis is the most common genetic disorder in the Western world. However, early diagnosis allows for appropriate treatment and the prevention of severe complications. Untreated, the condition usually leads to premature death.

Despite this, there is no population screening in Australia for the genetic condition. As a consequence, haemochromatosis is almost certainly the most underdiagnosed deadly disease in the nation. Therefore, it seems likely that this disease has killed many more Australians in recent years than any other disease, including COVID-19.

The arguments against population testing are weak. One reason cited is that, because individuals with the gene pair do not always develop the symptoms of haemochromatosis, population screening is not "cost-effective" and could lead to "undue anxiety". Another is that it may lead to potential health insurance and employment discrimination.

The more likely explanation is a lack of awareness from the very much at-risk general public. Because the deaths that result from undiagnosed haemochromatosis are from secondary diseases and organ failures emerging as a result of iron toxicity, there is no way of definitively ascribing the cause of death among the undiagnosed to the disorder.

A cynical mind might deduce that this uncertainty, combined with the fact most sufferers don’t die until their '50s or '60s, is the primary reason the Government does not inform the public about the dangers of HH. People dying before they reach retirement age is a boost to public coffers — at least until they get sick and need to use the public health system.

Dave’s Story 6: Dying too young

These days, my blood tests reveal my liver count and ferritin levels are all within the normal range. I’m healthy and suffer no ill effects, apart perhaps from a slight lethargy sometimes. And if I remain diligent in donating blood, it shouldn’t be the iron that kills me. I may even reach three score years and ten, who knows?

But I was lucky. I got a blood test by chance early enough to save me.

The average life expectancy in this country has been above 80 for quite a few years. Yet, my father Gordon died in 1991 at the age of 61, just ten years older than I am now at the time of writing. According to the doctors, he died as a result of stomach cancer. But was that the whole story?

Because HH only occurs where both parents are carriers, we know for certain my Dad carried at least one of the HH genes. But did he have both? It’s impossible to know since, even after being diagnosed with cancer, he was never given a genetic test for this disorder.

A final word: How you can save lives ─ maybe even your own

The first week of June is World Haemochromatosis Week. Haemochromatosis Australia has done a great job in staging events of all types to raise awareness about this deadly and shockingly pervasive disease. If you are feeling generous, slip them a few bucks to continue their great work.

Please also share this article to help raise awareness of haemochromatosis. You might just save a life.

You might also consider sending this to your local MP, asking why the Government won’t fund population screenings for this common deadly disease. If we get nationwide blood tests for 40-year-olds, you might just save a great many lives.

Most importantly, if you are Caucasian, over 40, and haven’t already done so, go to the doctor and ask for a simple blood test. It can lead not only to the identification of HH but also to a range of other conditions.

You have too much to live for to die before your time.

Haemochromatosis Australia is a not-for-profit, run entirely by volunteers. Support them on Twitter @haemaus, as well as on Facebook.

During World Haemochromatosis Week, VA acknowledges the work of @HaemAus which is a non-profit run entirely by volunteers. Haemochromatosis Australia is the primary advocacy group for Australians who provide support and promote awareness, early diagnosis and research. pic.twitter.com/nklsAv0BfN

— Volunteering Australia (@VolunteeringAus) June 6, 2022

IA founder David G Donovan writes a regular weekly column on Tuesday mornings but was a little late this week. Follow Dave on Twitter @davrosz. Also, follow Independent Australia on Twitter @independentaus, on Facebook HERE and on Instagram HERE.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.