As a country that once welcomed migrants with open arms, Australia's current treatment of asylum seekers is gut-wrenching, writes Kristin Perissinotto.

IN 2016, the last time we had a successful census, 49.3 per cent of Australians were either born overseas or had one parent born overseas — 28.5 per cent were themselves born overseas.

It's not currently documented, but even more Aussies will have at least one grandparent born overseas, including me. Both my paternal and maternal grandfathers were immigrants from Europe. They have both passed away now. One was in the last year and in the final years of his life, I learned about his arrival to Australia with his brother. They travelled here from Italy when Australia was making a big push for immigrants, due to slowing population growth.

This story isn't particularly unique. Growing up, I had friends with Opas and Omas, Yayas and Pappoús, Nonnas and Nonnos. Many Millenials like myself have some heritage or relative in the not-too-distant past that hails from overseas. Lots of us have heard a "Now-where's-that-from?" when we give our full names at the shop or to a bank teller.

Australia is very multicultural — it's evidenced by our statistics. Many of us have relatives that were welcomed here with open arms. Of course, there was discrimination and teasing and many reiterations of the term "wog", which has been used to describe countless ethnic backgrounds. But the Australian Government welcomed these migrants with open arms. We needed them. We stamped their passports and whipped up visas. We gave out permanent residencies and citizenships like they were stubby coolers at a tool store.

But we don't do that anymore. Instead, we lock persecuted families from war-torn countries in "prisons", claiming they are simply in "administrative detention". Our Federal Government goes to great lengths to keep people seeking asylum away from "card-carrying Aussies".

It vilifies children and the parents who just wanted a better life for them — much like the European immigrants who left their families behind in order to have the chance to work somewhere where jobs were plentiful: Australia. A land of abundance, religious freedom, space and legitimate democracy. A land without war and the threat of persecution. At least, that's the story they were told.

Every Australian knows someone who was born overseas, or whose parent was born overseas. Many people will claim immigrants are the hardest workers they know. And maybe that's because they had to be.

It's widely recognised that there's a specific "immigrant mindset". A laser focus on the future, on hard work, on a better opportunity for their family, on the individual responsibility of building something that can be passed on — be that a business, a home, or a strong work ethic.

A common retort to this argument is that some migrants come "the right way". The legal way. They applied for visas, lived in "stopover" countries and were granted asylum before even leaving the shores of their homeland. They had jobs lined up already, family to stay with. They came on planes – not boats – with packed bags, not just the clothes they could carry. They are productive members of society, working for their own money, not benefitting from taxpayer dollars.

However:

- People seeking asylum who come via boat are statistically more likely to qualify for refugee status than those arriving by plane.

- It is not illegal to seek asylum in Australia, which is why the Government claims detainees are in "administrative detention", despite living in worse conditions than some Australian prisoners.

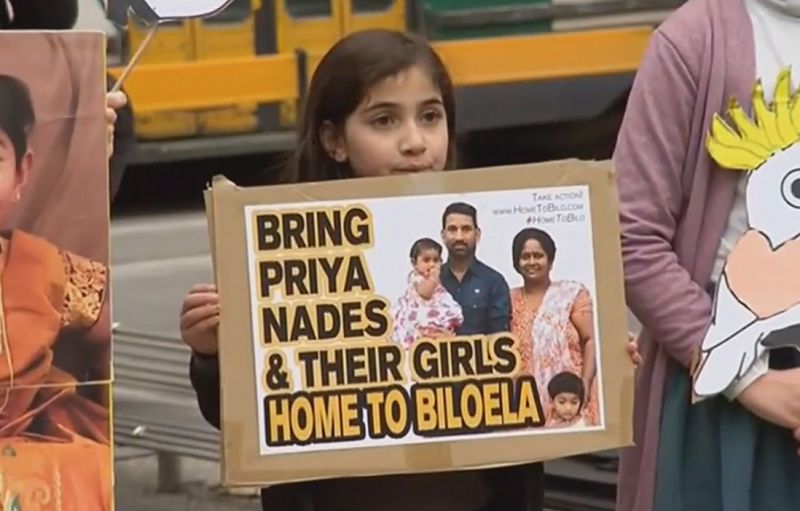

- Settling refugees does not burden the taxpayer, in fact, we spend significantly more detaining people than we do settling. We have spent $11 million (so far) detaining one Tamil family alone. They were working, supporting themselves in Biloela before being sent back to detention three years ago.

- Many of these families fled persecution (which should qualify them for refugee status) and simply did not have the option to use alternate methods to get to Australia. Fleeing your country in secret is risky and only done in the direst circumstances.

Last week was Refugee Week (20-26 June 2021). And I'd urge every Australian to think of the 1,700-odd detainees situated on and offshore as the same as that parent, grandparent, friend, or colleague who wasn't born in this country. The Government wants us to believe these detainees are different. Villians. A threat to our national security.

I'd maintain that this is the reason the Sri Lankan family from Biloela has had so much community support. Their photos have been in the media relentlessly. The photo of little four-year-old Tharnicaa in the hospital, crying as her sister Kopika kissed her on the cheek was everywhere. Who can ignore the plight of two innocent children – one with a serious illness? If we could see into detention centres, we'd see more heartbreaking images just like that one.

We must not be scared of those in detention. It is them who should be scared of us. A country with laws so tight that it is only via immense pressure that a bridging visa is granted to a child who was born right here in Queensland.

It was announced recently that three of the four members of the Biloela family are receiving bridging visas. It's currently unknown why the youngest, Tharnicaa Murugappan, was not granted one. It's also questionable why her sister Kopika received one when she is an Australian citizen, born in the small Queensland town of Biloela.

If these people seeking asylum had a choice, they would have stayed put. They would have stayed among family and friends. They would have stayed in the country where they knew the rules, knew the language, knew the landscape.

They travelled here because they needed to. And it's our responsibility as Australians – as citizens of a multicultural country, as children, grandchildren and friends of migrants – to not be afraid of them. To understand them. And to welcome them.

Kristin Perissinotto is Chief Executive Officer of Cheek Media Co. She is a public relations and communications professional with experience in various industries, including nonprofit, finance and education.

This article was originally published on Cheek Media Co. and is republished with permission.

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.