We normally tend to think of suicide as a personal issue, a tragedy that occurs at the level of the individual — but shouldn’t the system take at least some responsibility?

I'VE JUST COMPLETED watching 13 Reasons Why, an excellent Netflix series about a teenager’s suicide and the 13 reasons (mainly people) why she commits it. The suicide scene is one of the most harrowing things I’ve ever witnessed on television.

I’m glad this show is airing: even though there’s increasing community talk of mental healthcare (consider the growing profile of organisations such as Beyond Blue and the Black Dog Institute), suicide remains a rather under-discussed topic. It’s still somewhat taboo. So the advent of a show like 13 Reasons Why makes it slightly less uncomfortable to have a conversation about it.

Of course, like many issues, the conversation tends to revolve around the individual: Why did they kill themselves? Were they deeply depressed at the time? Did they endure a harrowing crime? Was anyone aware they were feeling suicidal? Could anyone have prevented it?

These are all valid and vital questions. But as is the case with many/most phenomena, the mainstream tends to examine them almost exclusively from an agent-centred perspective — that is, on the level of subjectivity, selfhood. But suicide doesn’t occur in a vacuum: we, each one of us, inhabit a particular society that fundamentally shapes who we are and how we become. Each one of us is largely a product of these societies. We are victims and/or profiteers of it. So if we want to understand ourselves and our radical acts better, we need to understand our contexts better, our societies better, and especially the systems (economic, political, and so on) that run our societies. That run our lives.

Such as capitalism, for example.

In his book, Suicide, pioneering sociologist, Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), noticed something peculiar/disturbing about his own country (France) and other Western nations who, by the late-18th century, were well on the path of capitalism’s Industrial Revolution. He observed that materially wealthier countries experience relatively high rates of suicide among its citizens.

This trend continues today, and is perhaps intensifying, especially among younger people.

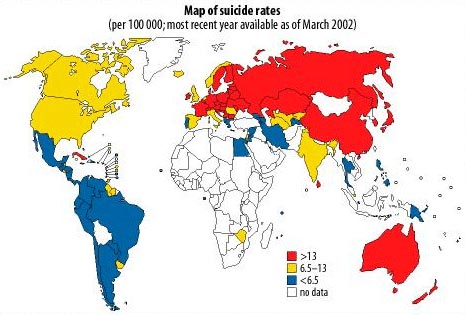

According to suicide.org, Australia is placed 44th in the world in terms of suicides per capita, while other economically-advanced countries rank as follows: Japan: 9th; South Korea 10th; France 18th; Switzerland 19th; Sweden 31st; USA 43rd.

Of course, we must always be wary of statistics; many nations are not even mentioned on the listing, which suggests to me that suicide remains taboo and any mention of it is therefore silenced. This might particularly apply to backward-thinking societies that still consider suicide some kind of “sin”.

But I do think the numbers tend to support Durkheim’s thesis: that our economically-advanced societies and all the bad (as well as the good) that comes with them – such as increasing isolation (another Durkheimian point) – form part of the abyss within which more and more people are finding themselves.

Now, I’m not claiming that suicide can be explained solely in social terms. That would merely reverse the fixation with agency. Such an explanation would ignore real factors, such as mental health issues, horrific experiences suffered by individuals and so on. Obviously, such factors need to be taken into account and addressed, so that those suicides that might be preventable are prevented from occurring.

But what I am saying is that the public conversation has mostly ignored the role that society and its systems play in pushing people towards this desperate act. But this is absolutely unsurprising: it’s in the interests of the elite that we don’t discover and discuss the link between the kind of society we live in and our rising suicide rates. For if we did, we might start exploring more life-affirming ways of living and working together.

The last thing I want to say is that, as was the case in 13 Reasons Why, suicide is often a brave act, a courageous last resort. This article is dedicated to those who have suicided ... and for those who are contemplating it.

If you feel like you are at risk of suicide, there are many services available in Australia to support you:

- Lifeline: 24 hour crisis support — 13 11 14

- Hold On To Life @ the Australian Suicide Prevention Foundation (24/7) — 1800 HOLDON (1800 465 366

)

) - Suicide Callback Service: 1300 659 467

(available 24/7)

(available 24/7)

Dr Mark Manolopoulos is a philosopher and an adjunct research associate at Monash University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Be good to yourself! Subscribe to IA for as little as $5.