We are addicted to private debt and those responsible for regulation have very little idea of what to do for the best, says Dr Steven Hail.

HAVE YOU NOTICED that the new Governor of the Reserve Bank, Philip Lowe, has been in the news a good deal of late?

He has brought into question the negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions, which have helped to support and inflate the housing market. He has drawn attention to Australia’s record level of household debt.

He has been explicit about the problems faced by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) board with respect to interest rate decisions. He has explained that, as the economy has not been growing remotely fast enough to achieve full employment, the encouragement of yet more household debt could push the financial system from a state of financial fragility to one of financial crisis.

I explained this recently on IA but was not expecting the governor to speak out so stridently, so soon.

Indeed, Philip Lowe may be channelling Hyman Minsky. The Australian housing market and Australian household debt bear all the hallmarks of an accident waiting to happen and are best understood from the perspective of Hyman Minsky’s "financial instability hypothesis".

Minsky, an economist who died in 1996, but whose work rose to global prominence only after the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, famously said "stability breeds instability" and argued that financial capitalism is naturally unstable upwards. Stability naturally leads to a boom, which in the absence of aptly designed regulations, inevitably leads on to a crash.

Minsky did not write mainly about household debt and property market bubbles, but the logic of his model is obviously applicable to the state we are now in. Modern-day Minskians, like Steve Keen, have for some time now been warning about the potential consequences of the approach to economic management, which has been used in Australia by both Coalition and Labor governments since the 1990s.

Suppose a growing demand for housing and a limited supply, backed by falling interest rates and the absence of any serious losses for property investors in recent times, generates positive expectations for capital gains in the property market and rising prices. Investors will see themselves making money from property speculation. Homeowners will see their paper wealth increasing as they stretch themselves to buy more expensive property. Those who take on the most debt – who gear up the most – will appear to make the most money.

Rags to riches stories of property speculators will abound. People will hold courses on how to make money from borrowing to buy, renovate and rent or sell on. Those looking for somewhere to live will stretch themselves, borrowing more than they can comfortably afford, just to get onto the so-called property ladder. All the while, prices will rise. And all the while, economists and other pundits working for those interest groups benefiting from a property boom will argue there is no bubble and that the whole thing is based on supply and demand, net migration, planning constraints and the rest.

But is it? Is it really? After all, in the end, the number of people without homes won’t matter to the property market if those people no longer have the wherewithal to buy the property. In the end, if you are buying and selling on, you will run out of people with the willingness to pay rising prices to sell on to.

Australia's #housing #bubble https://t.co/MwT9md2SMP #property

— Knut Cayce (@ModdityDodds) January 24, 2017

What happens next? Prices can start to fall and the market can quickly become very illiquid. A market with lots of investment buyers can become one where nobody wants to buy. Add on the possibility of rising interest rates, tightening banking regulation on investment loans and other mortgages – and a downturn in the economy generally – and you have the potential for a full-blown property crisis. It all depends, then, on how the government responds to an incipient crisis.

So far, Australia has dodged this bullet. Both Coalition and Labor governments have propped the market up with tax concessions and grants to buyers. It is these tax concessions that Philip Lowe is concerned about. The Rudd Government propped the whole economy up in the face of the global recession of 2009. What would happen next time? Would the Turnbull Government do likewise? Would the present government be so addicted to its mantra of "debt and deficits", ending "the age of entitlement", plugging an entirely imaginary "budget black hole" and not "spending like a drunken sailor", that in the event of a downturn they would fail to support demand and employment, see unemployment rise and trigger a property market crash that way?

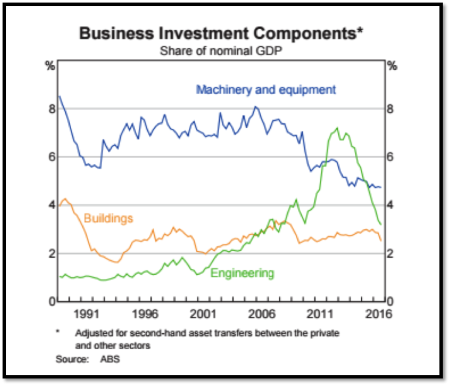

This scenario would be more than enough to bring the whole housing market down but while it might seem plausible, we have so much household debt in Australia now that it might not even be necessary. The housing bubble may well burst anyway — although saying for sure you know when this will happen in what is a complex and uncertain environment, is unwise. There are reasons for being concerned right now, though. Mining investment is in free fall and no other element of investment spending is taking up the slack.

(Source: rba.gov.au)

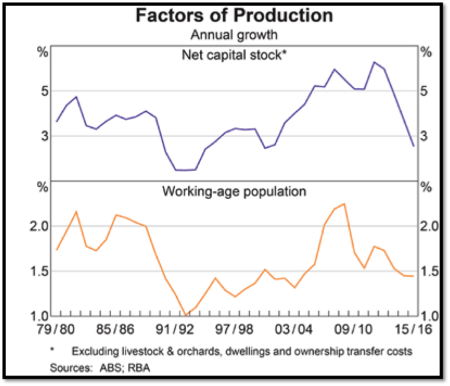

It would be wise for the Turnbull Government to be investing heavily in renewables, in transportation and in infrastructure generally over the next few years — but they have backed themselves into a fiscal corner with their rhetoric, so don’t feel they can do so. Wages are rising at the slowest rate in Australia’s modern history and what is now a much more unequal society is, if anything, becoming more unequal. Cutting weekend penalty rates does nothing to help with this.

(Source: rba.gov.au)

Minsky argued that periods of relative tranquillity lead economists and politicians to start believing that the economy and the financial system don’t need regulating at all — that the economy is a naturally stable, equilibrium-seeking system. So those in power remove the institutional constraints which helped to keep the economy stable in the first place. This has been happening in Australia and around the world for many years.

The modern generation of modern monetary theorists who have learned from Minsky – his contemporaries, like Abba Lerner and Wynne Godley, and his inspiration, J M Keynes – have been arguing for years now that people have forgotten the difference between a currency issuer and a currency user, and got completely confused about the appropriate role for the government and the government budget in economic management.

Consequently, they would argue, and I would concur, Australia has become a country addicted to private debt in a deregulated financial system, where those responsible for what regulation we still have are worried and trying to tighten up where they can, where the governor of the RBA is hopelessly conflicted and doesn’t know what best to do, and where neither the government nor the opposition has much of an idea what to do for the best.

We need equitable full employment. We need ecological sustainability and green investments. We need affordable housing. We need to manage a gradual deflation of an overvalued property market. We need everyone to understand that a non-government financial surplus, while private sector (and especially household) balance sheets are repaired, requires substantial fiscal deficits as far out as the eye can see. We need people to understand that this implies neither runaway inflation nor passing any sort of burden on to future generations.

We need some "adults in charge" – to fling that piece of rhetoric back at our government – who understand that the government is not a household, it is at the centre of our financial system, it is a currency issuer, it cannot run out of Australian dollars, and that the responsible thing for the Australian government to do over the next several years is to re-think the whole direction of economic and social policy and to run responsible fiscal deficits for the public purpose.

As I have said before, good luck Australia, you are going to need it!

You can read more by Dr Steven Hail at erablogdotcom, follow him on Twitter @StevenHailAus, as well as on Facebook at the Green Modern Monetary Theory and Practice.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Reserve Bank decision time: Good luck Australia! @StevenHailAus https://t.co/5FNK9H6cec @IndependentAus

— Michelle Pini (@vmp9) February 6, 2017

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

@billy_blog @StevenHailAus @stf18 Running out of money, budget emergencies & other neoliberal myths https://t.co/JewK5hMUuM @IndependentAus

— Paul Fagan (@paulbfagan) February 28, 2017

Value for money. Subscribe to IA for just $5.