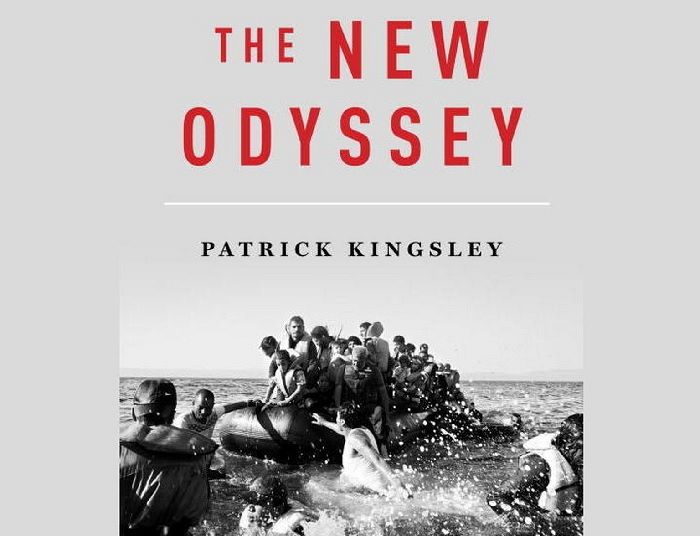

Kevin Bain reviews Patrick Kingsley's new book on the European refugee odyssey — 'their desperation will ultimately prove stronger than our isolationism'.

PATRICK KINGSLEY'S account of the 2015 refugee exodus from seventeen countries to Europe is racy reading in an ‘epic and personal’ style — as his publisher promises. Kingsley was the Guardian's immigration correspondent, reporting on refugees and migrants, people smugglers and traffickers. Nothing turns out to be simple and wicked problems abound in the refugee policy area.

While much of Europe was unwelcoming, Sweden and Germany were refugee-friendly and became preferred destinations — which caused a new wave of arrivals to the Greek islands. The result was a policy step back and an increase in temporary visas. Some suggest improving conditions in the home region as an obvious remedy for underdevelopment, but Kingsley tells us (p40) that studies show a small increase in GDP in a poor country will cause an increase in emigration, as higher income people in a failed state are more able to pay people smugglers.

If the answer for the persecuted Rohingya people is to repeat in Burma (Myanmar) the type of departure arrangements with the Vietnamese government of the late 1970s, it would facilitate the Government’s ethnic cleansing objectives.

The U.N. calls traffickers kidnappers or pimps, but smugglers come in shades of grey. While the default option, they can include governments, as we know in Australia, with motivations ranging from commerce to group solidarity. After Egypt’s President Morsi was ousted in 2013, Syrian refugees were unwelcome and were smuggled to Europe by Syrian networks in Egypt.

Labelling people as asylum seekers, refugees or migrants has undertones about their right to move, so Kingsley supports the neutral word "migrant" because 'it defines them by what they’re doing ... rather than why they’re doing it'. He estimates 25 per cent of them are fleeing poverty, not persecution, and NGO statements and reportage in Europe often use the phrase “mixed migration”.

Libya's two seas. (Kingsley 2016)#migration #MigrationEU #refugees pic.twitter.com/Z7PPlQzRMN

— Matti Välimäki (@mtaval) July 8, 2017

In practice, some who move for better life chances actually become refugees. A stable Libya offered employment up to 2011, but later migrants from the south entered a danger zone with no way back. Slavery and ransom raising was rife, with no police worthy of the name, so their new status as asylum seekers and their flight to Europe became unavoidable. The two rival governments seem to have become three as the Libyan nightmare continues. Increasing political tensions in Italy are driving renewed attempts – with UNHCR support – to stop the people flow. The UNHCR puts the current flow at 50 per cent for economic migrants into Libya, many of whom take boats to Europe.

Wars and civil conflict probably are more important proximate drivers of people movements in our region, but this is a useful discussion of language. Some refugee supporters argue that fear will always defeat facts and the insider-outsider discourse of governments and their allies can be undermined by a communications strategy of psychological “framing”.

Certainly, in Europe, the problem is sensitivities to border transgressions, rather than “invading hordes”. The people movement is primarily within Middle Eastern countries and the million people travelling to Europe in 2015 were few in relation to its 500 million residents. The current loss of momentum for now by the political Right is partly a reaction against Trump but, absent solutions, it may rise again. The toxic ethno-nationalism of today makes open borders just an interesting thought experiment.

The small African region with more #refugees than all of Europe | @Patrick Kingsley reports from #Borno #Nigeria https://t.co/6CpRNNECSW pic.twitter.com/lFVRE9Ipdk

— Joe English (@JoeEEnglish) November 26, 2016

Climate change is argued as the drying out of the “fertile crescent” in the Middle East, causing 5 million people to exodus from Syria in 2015-16, but the Refugee Convention is not designed for environmental refugees. Despite the evil deeds of people smugglers, the situation is so bad for Syrians they trust the sea more than the land. Those who are desperate enough to traverse deserts, seas and battlegrounds can’t be stopped. Fences and naval patrols only divert them to more porous borders. Leaving home is breaking the leash and many are prepared to die while trying for a better life.

Does Kingsley have solutions? Not if your definition is ending the flow of refugees. He says, 'their desperation will ultimately prove stronger than our isolationism', and policymakers will have to work out how to absorb them into European society. Massive resettlement in Europe now and in the long term would stem the flow and make the transit countries more relaxed about making life tolerable by extending social and work rights.

Are there special insights for us? The savings through scaling down the island prisons could be switched to the UNHCR, which would increase by five times the UNHCR budget for SE Asia. What a substantial improvement in deserving people’s lives that could deliver, while decreasing the urge to get on boats.

Are there special insights for us? The savings through scaling down the island prisons could be switched to the UNHCR, which would increase by five times the UNHCR budget for SE Asia. What a substantial improvement in deserving people’s lives that could deliver, while decreasing the urge to get on boats.

Politicians who cry crocodile tears about drownings while showing little concern about the damage they inflict on innocent people by slashing aid budgets have failed their own integrity test.

'The New Odyssey: The story of Europe’s Refugee Crisis', by Patrick Kingsley, is published by Guardian Books and Faber & Faber, 2016, 350 pages, $29.99.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Subscribe to IA. It's a good read.