Dr Laurie Keim reviews a new, rich book of poetry and, within it, he traces the fault lines in the heart of Australian colonialism.

AUSTRALIAN LITERATURE IS CRYING, if not crying out for a bold experiment to take us forward.

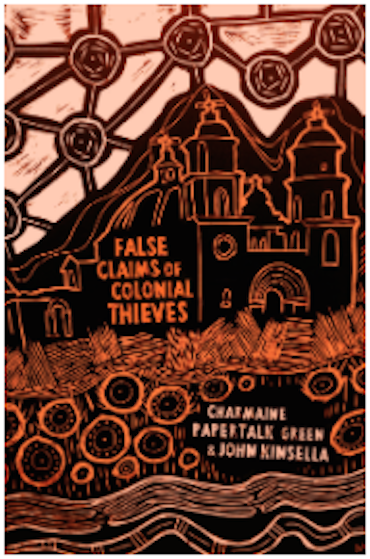

False Claims of Colonial Thieves is a volume of poetry, all the richer for being a collaboration. All the more interesting for being an experiment.

In the yellow corner, we have John Kinsella who is almost a walking definition of white privilege. Born in 1963, in Perth, Western Australia, teacher and writer, ambitious and prolific, he has published over 30 books. He has won numerous book awards and had poems published in the Times Literary Supplement and the Kenyon Review. He has taught at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of Churchill College. He commands enormous influence within literary circles in Australia.

In the green corner, we have Charmaine Papertalk Green who was born in Eradu, between Mullewa and Geraldton on Amangu country. She is a visual and installation artist, poet and writer. One cannot underestimate the courage and risk involved for her going head to head, page for page in a collaboration with one who carries such immense notoriety. It is one of the delights of this volume of poetry the way in which each shadow-boxes each other’s shadow.

On a structural level, the compulsion to read on is driven by a metanarrative which perhaps can never be resolved. On the one hand, we have Kinsella’s search for the noumenon, the thing-in-itself of the bush and land, the existential and experiential summary of his life. The force in many of his poems is this search for meaning, which in the end are only words, as words are where we must begin.

This is a white privileged concept with its specific history and economic rationale. Kinsella understands the difficulty of the task. He’s not trying to look for outs or hide under saltbush. Kinsella’s father worked for a mining company, on staff, foreman of the mechanic shed (if the stories are to be taken in an autobiographical way).

Green, on the other hand, is searching for the meaning of country which has been stolen, obliterated, poisoned and exported in rolling stock — all to fuel an economic system that barely has a reference to country itself. The conflict of the metanarrative is that Kinsella’s land and bush can never be Green’s country. Country, like some semantic aquifer, renews itself and delivers meaning in the same way Aboriginal children playing on the mullock heaps of tailings recall stories of the disturbed dead.

Country and land are separated by a schism of cultural practice and accumulated history. They are the antagonists in this narrative and organise the stories into separate frames. Yet the beauty of this book is the courage to push on through pain and loss and see if an understanding of some sort is possible. Kinsella is defined by white privilege but he gave it a go because to ignore such a gaping fault line in the hearts of Australians is no answer either. The poet steps up to the plate and swings with gusto.

With a touch of imagination, you can imagine book clubs all over Australia setting this book for the forthcoming month. Then, imagine the start of a conversation in which – for the first time – the systematic assumptions which maintain racism in this country are slowly unpicked and disposed of — for all time.

Green anticipates what this conversation will require:

You don’t want me to talk about

Past injustices, cultural cruelty, cultural genocide

And the cultural pain that is left behind

It’s a shared true history — let us heal

"Shared" and "true" are welded together and you cannot have one without the other. The "true" is not singular, either, but multi-vocal, requiring an immense amount of listening by whites to Indigenous claims, stories and tears. You cannot be optimistic in this debate without being courageous.

An enormous amount of honour has been lost and to cross the fault lines is to hear whose fault it was and the faulty assumptions upon which it was based.

Kinsella suggests we might rub salt into the wound to get us going:

Salt wraiths leave trails —

salt breaking through clean ground.

Where the salt saturates

they are the white ache

of pillar, arches, sheets:

The white must and will ache if we are to dissolve the pillars of racism and the arches of white privilege through which white faces crowd. I cannot emphasise too strongly there are moments of revision and conversion ordained in these often beautiful poems. It takes another mind for a poem to exist.

A poem, like the best conversation, exists in the spaces between people in the avenues and byways of passionate speech. At the critical moments in this volume, Kinsella offers us the poetry we need.

Here is his grandmother’s story taking, as poetry does, the reader to the edge of imagined limits:

She told me she ‘watched the blackfellas’

through the hessian curtains, watched

them go out past the town limits,

out past the claims, out beyond

the furthest wanderings of the prospectors,

out where there was a truth she knew

was so close to home, if only

she understood how to see.

All the components of understanding are presented here: the silent observation, getting beyond the border of our limitations, past all the claims and counterclaims, the exclusive ownership, past the prospectors and the carpetbaggers, past the stereotypes. Wanting, instead, to see instead the thing-in-itself inside us, which links us to another’s truth, our country, the land.

Find out more about 'False Claims of Colonial Thieves' at Magabala Books here.

You can read more by Dr Laurie Keim on his blog.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

Get chapter and verse. Subscribe to IA.