The future for young Australian workers looks dire with news their income was well in decline before COVID-19. Sam Brennan reports.

THERE IS AN assumption that people become better off over time.

This is a fair assumption, too, considering for 100 years every new generation of Australians has moved out of their parents’ house with a good wage and started the climb up an ever-growing job ladder.

But now, young people have been pushed off that ladder, are unable to afford a house and in what could be the first time in Australian history – according to a Grattan Institute report – young people's real income has declined over the previous ten years.

At the same time, Productivity Commission research paper, 'Why did young people's incomes decline?', found those above the age of 35 have seen their real income increase.

This decline has occurred: to men and women; to those in the city and the outback; to people who went to university; to Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and to those with a disability and those without — nearly every way you cut it, young Australians are making less.

Not only was this decline seen in wages, but also in government payments and investment returns. Every form of income has declined, with one exception — young people have seen a rise in money transfers from their parents.

This raises the questions: Why are young Australians facing a situation not experienced before? Why are they worse off?

Australia’s two economies

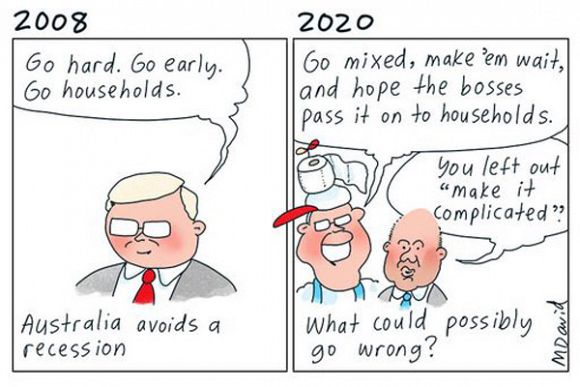

Australia emerged from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in pretty good shape when compared to the rest of the world. This was due in part to the stimulus policies of the Labor Government as well as the mining boom.

But if we emerged from the GFC relatively unscathed, as is widely believed, how come wages were stagnating? Why were people working fewer hours? Why was growth sluggish?

The Productivity Commission report showed that after 2008, Australia was split into two economies.

People older than 35 who entered the GFC with a job, house and financial security, saw their wages grow. They invested in housing and even saw an increase in benefits from the Labor Government. But if you were under 35, then the only jobs around were part-time – in a profession that you didn’t study – for low pay, with no prospect of promotion and dwindling government benefits to back you up.

The lack of other options means that workers also accepted worse conditions, as director of Young Workers Centre Felicity Sowerbutts told Independent Australia:

“Since our community legal centre was launched in 2016, 65 per cent of what we’ve been dealing with relates to wage theft. Many bosses believe they can get away with underpaying wages and superannuation.”

How did these two economies form in parallel with each other?

Breaking into the job market

During the GFC, government stimulus allowed businesses to keep a lot of their staff, but businesses were not likely to expand. Therefore, young people were unable to break into the job market. This was exacerbated by women entering the workforce and people working longer – thanks to increasing retirement age – meaning labour supply was on the rise without a corresponding demand.

Employers coming out of the GFC decided it was better to keep their current workers rather than expand and hire new employees.

But Australia’s unemployment rate has been steady. In the face of terrible job prospects, young Australians, instead, accepted part-time or casual contracts, working fewer hours as shown by the underemployment rate.

The graph below shows that underemployment for young people has grown since the GFC and is currently double the rate of older people.

Lifelong learning

The Productivity Commission report noted that after the GFC: 'Faced with high youth unemployment rates, young people were spending more time in education as an alternative to unemployment.' This resulted in increasingly educated young people accepting work that didn’t utilise their skills while pushing less educated people out of these jobs.

Furthermore, wage decline was a generational phenomenon, not an industry-based one. The Productivity Commission report also said, 'most occupations contributed little (or negatively) to wage rate growth for workers aged 20-34, while all occupations contributed positively to wage rate growth for workers aged 35-54'.

The stagnation in wages is not a matter of lack of education or even studying in the wrong area. It is strange that the Morrison Government pushes reform based on the principle that young people can get better jobs if they study more, in specific areas. This won’t fix the issue that there are too few jobs that pay too little.

It will not be the first time government has failed Australia's youth.

The government won’t help

The myth of the lazy youngster, dependent on government handouts, was also dispelled by the Productivity Commission report.

A series of government decisions has slowly chipped away at government payments to young people. Recipients of student Youth Allowance, aged 15-20, decreased by 60 per cent between 2002-2019 due to tightening eligibility. Lower payment for Newstart – now JobSeeker – as well as restrictions for Parenting Payment, only further reduced youth benefits.

While payments for youth decreased, pensions and family payments for older people grew. As such, young people not only saw wages go down while their elders saw a rise, but saw the same thing happen with government payments.

COVID-19 and the future for youth workers

Predating COVID-19, the Productivity Commission report draws on figures up to 2018. All the issues it found – casualisation of the workforce, declining hours and a slump in labour demand – have significantly worsened.

This is well known by Sowerbutts who also told Independent Australia:

"Many young workers have never had a secure job in their lives. COVID-19 has really highlighted these issues.”

However, she added:

“It’s certainly an opportunity to rebuild and reimagine our future, dealing with the negative impacts of insecure, low paid work and investing in our workforce with quality and affordable education and training.”

Correcting these issues will be monumental. The Productivity Commission report shows that any attempt at reconstruction post-COVID-19 which simply seeks to return to the norm will be woefully inadequate.

Previous recessions have shown us this can be achieved through comprehensive and far-reaching programs. Proposals such as the Australian Council of Trade Unions' plan for economic reconstruction or a version of an employment-focused "Green New Deal" could offer some hope.

Sam Brennan is a freelance journalist. You can follow him on Twitter @samkbren.

Related Articles

- Australia's unemployment crisis: The job-seeker’s game of musical chairs

- Australia’s unemployment ranking statistics now worst ever

- Scomo's latest welfare cuts: 130,000 sole parents lose out

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.