The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that a need for media information clear in scientific method and concepts has never been more crucial, writes Dr Peter Fisher.

THE PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLES are the foundations for policy when it has to deal with weakly understood causes of potential catastrophic or irreversible events and where protective decisions require certain and costly policy interventions that may not solve the problem that they are designed to correct.

South Australia's Chief Public Health Officer, Professor Nicola Spurrier, last month stated she had no regrets about her COVID-19 lockdown advice; the “pause” had allowed contact tracers to get on top of the Parafield cluster. This didn’t stop the media channelling the on-then-off-again restrictions as ‘a debacle’. A regional Liberal MP entered the fray arguing that ‘the balance between public health and the economy had been lost’.

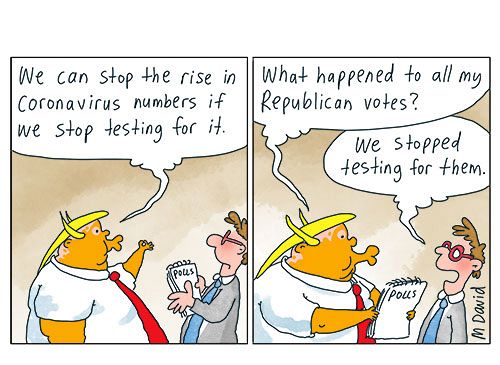

It’s an example of a problem confronting some politicians and media in getting their heads around the intricacies of science and the way empirical knowledge is advanced. Normally, uncertainties are played out/resolved in the literature — an ecosphere of science-communication built around peer review. With a knowledge frontier pushing forward and no end of preprints, differences of emphasis or disagreements have been in full public view of late, a ready source of clickbait.

And, whereas few of us care as to what goes with zippy controversies like whether worms orient themselves with the Earth’s magnetic field, matters are patently different when whole societies are facing an existential threat.

Handling uncertainty in scientific advice

There's no denying that science's measured statements often fail to fulfil our yearning for black-and-white answers. Instead, they tend to reflect a plurality of opinion, which is what drives scientific debate — a debate where the language is careful and often qualified. The sort of clarity craved by politicians and regulators may not always be forthcoming.

To come to terms with the twists and turns of these debates, it's important to grasp how complex scientific conclusions unfold. Advances in knowledge can run in leaps and bounds. Tugs of war can develop between camps with opposing hypotheses, with things swinging back and forth before consolidating in a particular direction. And there's the uncertainty created by plain bad science and poor experimental design.

These sorts of unknowns can also be underplayed or overplayed for political advantage.

Ground rules for communicating: A go-to for scientists

A multi-disciplinary group of Cambridge academics have concluded that uncertainties need to be made explicit and their implications transparently taken into account in decision making. They were concerned that researchers have not always been exemplary in acknowledging unknowns with respect to the virus. The group has been collecting data on issues like how to communicate uncertainty, how audiences decide what evidence to trust and how narratives affect people’s decision-making.

Their aim is to design communications that do not lead people to a particular decision, but help them to understand what is known about a topic and to make up their own minds on the basis of that evidence. Further, it is important to be clear about motivations, present data fully and clearly and share sources.

This is a tough ask. It’s compounded by people outside the scientific tent — notably journalists, columnists and lay commentators on panel shows. Especially telling were questions garlanded by long presumptive prefaces directed to Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews and Chief Health Officer Professor Brett Sutton (which they handled with stellar patience and aplomb) during their 120-odd press conferences in Melbourne.

Could it be that the paucity of scientific acumen on show goes back to a lack of science content in our journalism degrees? In a world wracked by far-reaching change and complexity, there’s surely a need for a media that is savvy with the scientific method and concepts.

Better safe than sorry

The qualification of an abundance of caution which regularly featured during those COVID-19 press conferences takes its cue from the Precautionary Principle, which has been adopted in a variety of shapes and forms at international, European Union and national levels.

It was formally adopted by the European Environment Agency in 2001 and a year later by the EU which specified that:

‘...measures, although provisional, to be maintained as long as the scientific data remain incomplete, imprecise or inconclusive and as long as the risk is considered too high to be imposed on society.’

On every account, the pandemic meets these stipulations and, as such, is a cornerstone for epidemiologists concerned with the ethical import of delays in detection of risks to human health ethics.

The virus has also identified a need for greater science-based thinking in mainstream public policy and all credit to the state premiers here. Equally so, in the U.S. where the incoming Biden-Harris Administration is planning to restore science to the top echelons of government.

Kitting up for the Anthropocene

That’s especially important in a world pitted against the destructive forces of the Anthropocene — coral bleaching, catastrophic wildfires, sea ice loss and horrific floods not to mention accelerating species extinctions. Virologists caution, too, that there are other bat viruses capable of making the jump over to humans which could see recurrent pandemics join global heating as dual ongoing threats. And, they’re also warning of a connection between human intrusion into wild habitats and pandemics.

The close interconnections between different elements within the health, city form, emissions and wildlife portfolios, such as lessening infection risk by shifting away from high people settings, will challenge planners.

In this period, there will be a torrent of stuff about endurance requiring scrutiny. Being able to cast questions which help readers/viewers/bloggers to understand what is known about a topic and to make up their own minds on the basis of that evidence is a sound way forward — to take guidance from Cambridge University.

Science certainly allows better, more informed choices on serious, complex issues (sometimes of its own making as new technologies bring further difficult choices), but it can't make those decisions for us.

A new generation of science-literate journalists

To get to that position requires new mindsets, new training regimes and co-operative ventures. There are a number of models here.

One is Climate Now, a global journalism initiative committed to more and better coverage of a defining story of our time involving over 400 news outlets with a combined audience approaching 2 billion people — and growing. Another is a training hub for African journalists who convene virtually for COVID-19 crisis reporting. It aims to provide core skills and information, assisted by scientific trainers, needed to report on the pandemic and its impact on economies, health care systems and communities.

But back to source is no less important. A reorientation of journalism curricular at our universities would see, at the very least, a science presence and not just as an elective. And dividends.

That’s fundamental to negotiating the Anthropocene.

Dr Peter Fisher is an Adjunct Professor at the School of Architecture & Built Environment, Deakin University.

Related Articles

- Mainstream media circles the wagons

- 'Press release journalism' favours Morrison and the Liberal Party

- Mainstream media presumption of guilt threatens Pell and others' prosecutions

- Australian media march to two different drums

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.