While enacting an Indigenous Voice to Parliament is crucial, a broader discussion must also take place about Australia's archaic 'Constitution' and the benefits of embracing a republic, writes Dr Klaas Woldring.

THE PROPOSED Indigenous Voice to Parliament surely is a long overdue recognition of the presence of people on this continent for over 60,000 years. But there is more to do — the Mabo decision made this very obvious.

In 1992 the High Court of Australia recognised that a group of Torres Strait Islanders, led by land rights campaigner Eddie Mabo, held ownership of Mer (Murray Island).

The Court also held that native title existed for all Indigenous people. That is now 30 years ago. This is still not recognised in the archaic Australian Constitution — the 3% of Indigenous people populating Australia have no practical political clout.

While there has been significant social recognition (acknowledgement) of “First Nations” status at public meetings, demands for a treaty between sovereign nations require clarification. Similarly, the notion of a colonial "invasion” has also gained ground. A need for compromise and realism has presented itself — a republic must address such issues. In this process, Voice is a first step.

Significantly, the term "invasion" can have different meanings. For European countries occupied by the Nazis, the invasion at the Normandy beaches in 1944 was in fact a major liberation.

James Cook's arrival at the Australian East Coast resulting in the settlement of excess British prisoners in 1788 was not an invasion like that. There certainly was awareness of Indigenous people living there but not in a developed sovereign country with legal status known as such.

Later, certainly by 1901, there was knowledge of numerous separate Indigenous tribes. The omission of reference to Indigenous people in the 1901 colonial Constitution confirms their lack of recognition as citizens.

While most colonial powers handed over control of “their” colonies by 1965, no such change happened in Australia. The only change here, thus far, has been that Indigenous people would be counted as persons for the purpose of elections.

The referendum to achieve that, in 1967, had massive support from Australian citizens – nearly 91% – an encouraging sign. However, progress since then has been very slow.

The major political parties have promoted some prominent Indigenous people to Senate positions or winnable seats in the House of Representatives — currently a total of 11. Of course, the small percentage of the total population doesn’t help, especially not in the single-member district system. The case for a Voice is strong but much more can be and should be done constitutionally, ideally before another republic campaign or in combination.

A proportional electoral system would stimulate the potential for all parties to attract votes from Indigenous people and present Indigenous candidates. A new Constitution could also guarantee a limited number of fixed seats for Indigenous people if required.

However, the demand for a prior treaty between "sovereign" peoples, the Indigenous 3% and the remainder of the population, is problematic. Our republic cannot have double sovereignty. It needs to reflect one sovereign nation anchored in a treaty of settlement — a compromise based on the Mabo case.

As an academic who has lived some years in apartheid South Africa, my PhD centred on race relations in that country. As a result, I became involved in managing a course on Aboriginal activism at Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education (NRCAE) in Lismore, originally designed by late Professor Colin Tatz, then of New England University.

It was a three-year exercise for teacher education students, funded by the then Department of Aboriginal Affairs. I met several well-known Indigenous activists at the time — they were really the teachers for a few days, speaking from personal experiences (1976 to 1979). However, progress towards Indigenous recognition and advancement since that time has still been slow. Why is this so?

As George Megalogenis, a child of Greek migrants, argued in a recent article, 'we need the Voice to thrive'. His piece concentrates on the slow relative change by comparing three major population sections: "old Australians", "new Australians" and "First Australians".

At the time of the failed republic referendum of 1999 when the republic was rejected, he notes the following breakdown: old Australians – 55%, new Australians – 41% and First Australians – nearly 4%.

From the census of 2021, the breakdown was as follows: old Australians – 45%, new Australians – 51% and First Australians – 4%. So, the dominance of the old "national story tellers", suggested by the republic referendum failure, has declined and will decline further.

Megalogenis makes it clear that individual differences will exist in the two main groups but broadly speaking, the shift to new Australians' views is likely to favour majority support for the Voice referendum.

Anthony Albanese has ruled out a call for the Indigenous Voice to be legislated prior to a referendum (which, of course, could be repealed by a conservative government in the future).

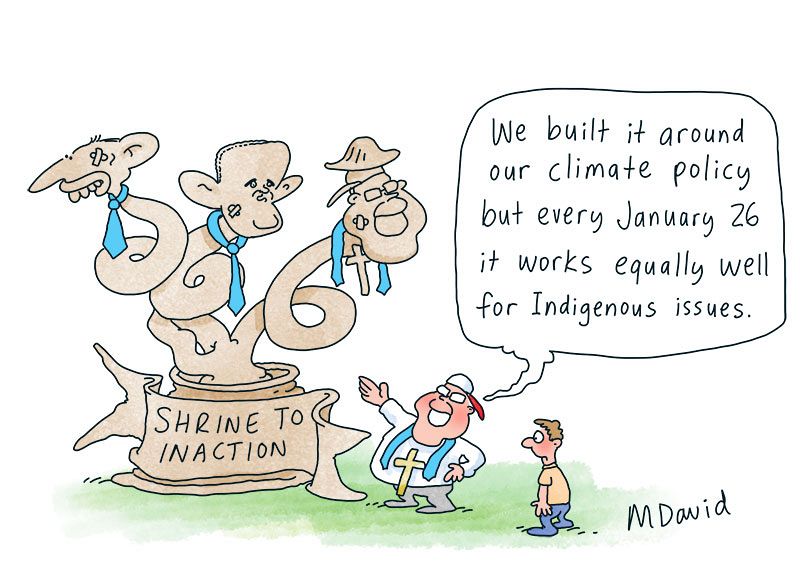

The National Party in Queensland has declared to support the NO vote. Other waverers say they need more detail. One other aspect cannot be known at this stage: the intensity of the NO and the YES vote.

In his article 'Has it been a bad week for the Voice? Yes and No', Peter Hartcher discusses the attitudes of Peter Dutton, the romp of the Liberal Party and the NO position of the National Party. The issue overall is: will Australia and the Albanese Government allow themselves to be dictated to by the former Coalition?

The abandonment by the Teal independents of yesteryear's government has been a refreshing message for Australia. They support the YES vote.

However, a much broader discussion needs to take place about the entire archaic Australian Constitution which is still colonial in essence. A recent lively Q&A devoted to the Voice demonstrated that.

Voters need more detail about the referendum. Perhaps a public crash course about this issue, as well as the Constitution, could be organised by the ABC?

Dr Klaas Woldring is a former associate professor at Southern Cross University and former convenor of ABC Friends (Central Coast).

Related Articles

- Constitutional change requires a courageous strategy

- An Australian republic should start with a new Constitution

- America's Right-wing destroying U.S. democracy

- Let's start talking about a republic

- Why the English Monarchy has no place in Australia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.