When we head to the polling booths this May, we need to make choices based on Australia's economic future, writes Dr Kim Sawyer.

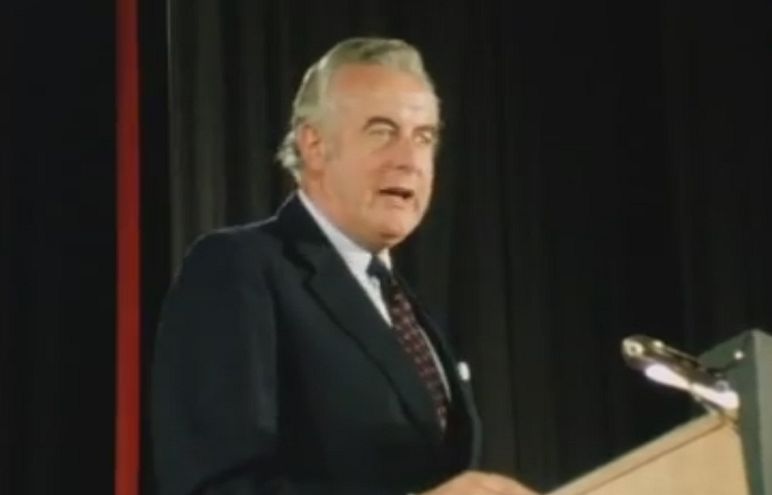

THE LAST TIME Australia had an election on May 18 was in 1974. It was an election fought on the Whitlam Government reforms and economic management. The Whitlam reforms included 18-year-old voting rights, equal pay, tariff reductions and universal health care.

The reforms now seem obvious, but at the time were strongly contested. Their acceptance is a signature of how far we have come. The Whitlam era prefaced the modern election where reform competes with economic stability. And this election will be no different.

The 1974 election was notable for who was elected. Two of Australia’s most significant policy makers, John Howard and John Dawkins, were first elected in 1974. Howard is credited with the GST, gun laws and refugee policy and Dawkins with the reforms to higher education. Every election inducts new politicians. Elections are not just about the current leaders but the leaders who follow; not just about the current policies but the policies that follow.

With the federal election around the corner have you started thinking about who you are going to vote for? Here's is some key policies you should consider before entering the ballot box. I know where I'm sending my vote. https://t.co/7zkJg2OK91

— Beyond Broking (@BeyondBroking) April 17, 2019

When we go to the polls, we elect representatives to represent the future, not the past. We have to have the foresight to elect decision-makers of the future. This election, more than most, is about the future.

Comparing headline data, we see how economic management has changed since 1974 when inflation was 15% and housing loan rates 8%. Today, neither will be an issue. What is different today is the structure of the economy, which is now more open with free exchange rates and free trade. We have become dependent on foreign investment but also on policies enabled since 1974 related to negative gearing, dividend imputation, superannuation and deregulation.

Our economy is leveraged to these policies. Debt, which was not a problem in 1974, is now a problem. In 1974, net Government debt was negative and household debt less than 30% of GDP — today net Government debt is 18% of GDP and household debt 120% of GDP. Debt is a long-term issue which should be highlighted but will be footnoted. Issues like taxation will dominate because voters can do the calculations to see what it means for them. The self-interest of the politician always resonates with the self-interest of the voter.

In a sense, the reason we cannot deal with long-term policy has to do with the electoral cycle. We have locked in a three-year cycle which is much less than three years. Since 1974, the average term of the Parliament has been a little more than two-and-a-half years.

An independent observer may wonder why we don’t have fixed four-year terms with an election date mandated by the Parliament. An independent observer may also wonder why we don’t use elections for referendums to determine questions such as whether Australia should become a republic or whether we need Constitutional reform for issues like Section 44. The benefit of a fixed electoral cycle has been ignored by politicians. Perhaps it is not in their interest.

Much of the noise we heard tonight on #qanda will pass - but their policies will stay. This policy comparison spreadsheet shows the huge differences between the major Parties #auspol > https://t.co/GLgxmsa1c8

— Denise Shrivell (@deniseshrivell) April 15, 2019

An issue that has punctuated politics since 1974 is the unaccountability of politicians. Most of us cannot afford the influence required to access them. Most of us will never access the sinecures they access. Most of us cannot abuse work entitlements the way some politicians have abused theirs. Many politicians have become unrepresentative of those they represent. They are not as accountable as they should be. There are a number of reasons why.

Many voters are in seats which rarely change hands. The Australian Electoral Commission defines a marginal seat as one where the leading candidate receives less than 56% of the vote. Of the 151 seats contested at this election, only 43 are considered marginal. That means 108 candidates can be reasonably confident that what electors decided in 2016 they will decide again in 2019. When a politician is pre-selected for a safe seat it represents quite an annuity. The pre-selection process needs reform, perhaps a primary system, so that voters can have a say as to who is running before they run.

We have put too much faith in the self- regulation of politicians. Only now is a National Integrity Commission for breaches of public trust being considered. Yet this proposal was first mooted in 1994 when Parliamentary committees first considered public interest whistleblowing. Why so long? Perhaps it was not in the interest of politicians. As for other matters of governance, Australia has been slow to codify the rights and responsibilities of public officials.

We should hope this election leads to policy-making to address long-term issues. Long-term policy requires a longer electoral cycle and better political accountability. The dividend to the economy will be a lower risk premium. The dividend to us will be more accountable politicians.

Underlying the election battle is an intergenerational fight over income, wealth and the future. #ausbiz #auspol https://t.co/GEhGl0JExB

— Financial Review (@FinancialReview) April 17, 2019

Dr Kim Sawyer is a senior fellow in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne.

Great article from @GrogsGamut today, and not just because it cites our report with Anglicare from last year, The Cost of Privilege. See our full report here: https://t.co/hZiIISEYcehttps://t.co/o3pVjliwpz

— Per Capita (@percapita) April 18, 2019

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.