Voting in the Voice to Parliament could be a stepping stone towards eradicating the high amount of Indigenous incarceration, suicide and poverty, writes Gerry Georgatos.

THE ESCALATING crises endured by Australia's First Nations people are from “oppressors” foreign to the remnant peoples of villages destroyed by the oppressor. The language of the diabolically outrageous oppressor is catastrophically demonising and labelling and divisive and not just “coded”.

Let the oppressed and their advocates be at liberty to speak back in the language of their suffering and not in the reductionist language that compromises truth and allows the oppressor to go unaccountable, reducing the oppressed to beggars.

This is not about fighting fire with fire. It is about truth-telling. It is about contextualisation. It is about Voice(s).

The oppressor has institutional firepower. The mostly unrepresented oppressed have only their unheard voices. If voice is all they have then they must be amplified.

The oppressor, drunk with power, historically racially profiled — eugenics, segregation, assimilation. Negative flow effects from eugenic-geared policies continue, various forms of effective segregation are still realities and assimilation is the only deal — “swim or sink”. The “thou know us best” remains as bedrock. We can “Blackenise” assimilation all we want, with proportional Black workforces and “consultations”, but all we do is bring on more assimilation.

Resistance is met with your children taken, with gaols crammed with our brothers and sisters, with our people gaoled at the world’s highest rate, suiciding at abominable rates.

The departments of child protection are not any form of a village raising children but a cruel hoax, of a distilled inhibition of “thou know us best”. The removal of children has become a cheap first resort and a climate of fear. Take the children away. Poverty has become a crime to argue that an impoverished parent is unfit to rear a child and that an affluent parent is the best fit to rear children.

The abomination of one in 18 First Nations deaths by suicide each year should have long ago galvanised the nation and our governments to do all of what they could do — none of which they have done. Let the citadel hear without escape.

When disaggregated, we find that Australia from a racialised lens is the world’s mother of all gaolers of its First Nations people. One in six First Nations Australians living have been in prison. This is more than 150,000. The suicide toll, the prison toll and the child removal toll of Black children as indisputably intertwined, fated from the one inkwell.

If families were supported when they asked for help and if child protection acted as familial support, the suicide toll and rate would be significantly less, as would be the incarceration toll rate of First Nations people. Therefore, the sins of a nation that brought about the need for a Black struggle and have been the sinful works of one government after another continue in the present.

Departments must be made accountable and transparent. It is the call that the grimness of suicides in residential care, in out-of-home care, must be published annually and preferably in real time.

These child protection monoliths have conjured up investigation units and never-ending “care protection services”. The significant layer within these services is Kafkaesque — it is the poor that seems to be the target. Despite billions being allocated towards the national child protection budget each year, there is a “cry poor” by child protection authorities that more funds are needed to monitor vulnerable families. Each year, in every jurisdiction of the nation, child protection budgets increase and subsequently, the number of children removed increases.

When children are removed from their families over alleged emotional abuse and various other reasons, they are seldom provided with adequate healing and restorative therapies. The removal of a child from her or his family is a significant psychosocial hit. It goes straight to the validity of the psychosocial identity. It hurts and for many, this pain is unbearable.

For many, the trauma of removal is unresolvable, inescapable and relentless. For some, this trauma is also compounded with multiple composite traumas which may degenerate into disordered thinking and aggressive complex behaviours.

For the most part, child protection and family services should reconsider how they allocate their budgets and instead focus on genuinely assisting vulnerable families as opposed to the reductionist approach of removing children. Many child protection and family service workers are not skilled in any number of ways that should be requisite and are ill-qualified and inexperienced.

In our interfaces on behalf of families of child protection workers, we have been appalled by the low levels of skills and understandings of workers — by the horrifically and dangerously low level of seasoned expertise. I am describing what the Voice to Parliament may bring to the citadel.

Most families investigated by child protection authorities can navigate acute socioeconomic pressures – and even various assertive negative behaviours within their homes – including exposure to alcohol abuse, substance abuse and various psychological and psychiatric illnesses. The involvement and over-involvement of under-skilled but in practice overly judgemental child protection workers in general not only fail to assist, but compound vulnerabilities and is trauma-inducing.

There is a generated constancy of trauma. People make mistakes, they can wound each other. Empathy and redemptive forgiveness are likely with families, who for the most, are in the first instance intensively supported and thereafter left to themselves to work through their lot.

Child protection workers majorly invalidate people, diminish them and most certainly traumatise every family worker. It is a grim reality that 13.4% of the Australian population lives below the Henderson Poverty Line, but nationally, for First Nations Australians, the figure is at least 40% and another 20% in proximity.

Poverty should never be an excuse for the removal of children. It is a grim reality that about 10% of children live in families affected by substance misuse. But still, for most of these families, there is no genuine reason to remove most of the children that are removed. These families are already stressed and instead of being supported through their major stressors – for instance, substance misuse to core mental well-being – we impost more stressors on family members, and dump painful sanctimonious and unreasonable expectations. All Australians will benefit.

Reduce the child protection budgets and the child removals will be reduced. Radically reducing the budget will lead to a triage-based approach to at-risk children by the departments. I am obviously stating it appears there is more to be gained positively by child protection authorities being underfunded rather than overfunded.

In general, no society should be overinvolved in the lives of families. We argue that reducing child protection budgets is the most obvious immediate solution to radically reduce the shameful high child removal rates. Nearly half the children removed are under five years of age, when their form and content are in most need of their biological parents. All Australians will benefit.

The child protection monolith is washing into society stereotypes of parents and children who are being removed as “drugged-up”, “drunk”, “violent” and “incompetent”. Most of the parents are none of these. Stereotypes are often misused intentionally. All Australians will benefit.

Some children will need foster care, but our experience is that most children removed should have remained with their parents. In the case of the Black struggle to keep our children, they have been condemned by the reductionist aspiration to remove children to the care of kin. Children removed from their parents are traumatised. Parents who lose their children, even to other kin, are traumatised.

The reductionist aspiration that relative or kinship care is the way to go for children is not a solution. Kinship care is the best option for some children for a period, or permanently, but for most children, it is a damaging experience. Sisters and brothers need to be together where possible. This systematic attitude should be so inclined but is not.

The removal of a child from her or his family is dangerous. The world is never a perfect place and institutions should not act out as if it is or should be. The removal of a child can invalidate the individual, not just disrupt. Prisons are filling at an ever-increasing rate with individuals who, as children, were removed from their parents. It is our view that more than half the prison population were once children removed from their parents and for First Nations, thereabouts three-quarters.

It is our view they are the most elevated group to suicide and unnatural deaths. Unless we radically change policies and narratives to authentically work with families instead of tearing them to pieces, the number of children removed and the suicides of these children as adults will increase. All Australians will benefit.

Following the death of Mulrunji Doomadgee, the Palm Island Police Station was burnt to the ground. Nineteen years have passed since that fateful day — 19 November 2004. In the years since, there have been 400 Black lives lost in prison or police custody.

On that summery November day on Palm Island, Mulrunji was walking his dog. He was singing ‘Who Let the Dogs Out?’ A senior sergeant took issue. Less than 45 minutes later, Mulrunji was dead.

Earlier in the morning, on the last day of his life, Mulrunji visited his newborn niece. He celebrated with a little to drink. He had been carrying a bucket with a mud crab which he intended to sell. The walk from his sister’s house would be his last, though he had been in a joyous mood.

The senior sergeant was working alongside a First Nations police liaison officer when Mulrunji sang out, “Why does he help lock up his own people?”

Mulrunji kept on walking. It could have ended there, but the senior sergeant drove up to Mulrunji and arrested him for “creating a public nuisance”.

Mulrunji was bundled into the back of the police vehicle. There would be no mud crab selling, no further walk with his dog. The 36-year-old senior sergeant would soon be responsible for the death of Mulrunji, also 36 years old.

In September 2006, coroner Christine Clements found Mulrunji died of punches inflicted. Mulrunji’s liver had been split in two and was held together by a few blood vessels. He had lost at least one-and-a-half litres of blood.

Should we deny the Voice, deny the citadel to account for ways forward?

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus on social justice.

Related Articles

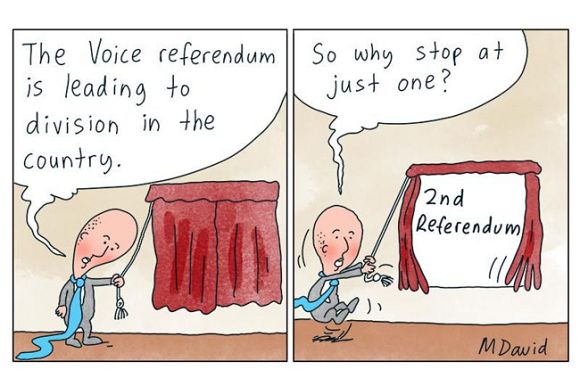

- Peter Dutton needs another referendum to find his Voice

- Amending Australia's shame through a unified Voice

- Voice Referendum can achieve even more success than in 1967

- Voice Referendum a step closer to an Australian republic

- Voting 'Yes' to the Voice is about more than just politics

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.