Leaving the establishment of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament to a referendum without a clearly defined model is a move headed for defeat, writes Professor John Quiggin.

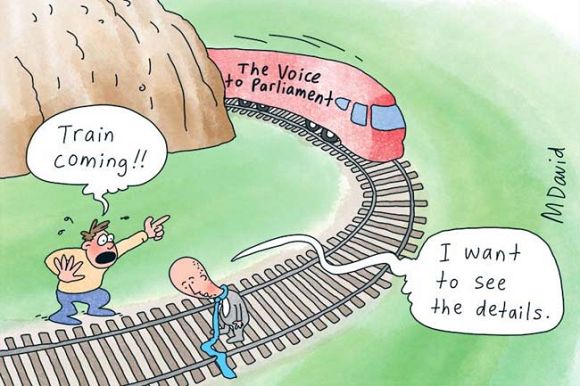

ON CURRENT INDICATIONS, the Albanese Government proposes to put forward a referendum allowing the establishment of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, without presenting any concrete proposal regarding its structure, role and so on. Unsurprisingly, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has seized on the lack of any detail to attack the referendum proposal, without taking any stand on the desirability or otherwise of a Voice.

Based on past experience, this almost certainly implies that the referendum is headed for defeat. No referendum granting substantial new powers to the Commonwealth Government has ever been passed. Referendums without bipartisan support have invariably failed. Why, then, is the Government taking this seemingly doomed approach to the question?

The answer appears to lie in a mistaken analysis of the 1999 referendum to establish an Australian republic, an analysis which I shared until recently. The implication drawn from the failure of the referendum was that it would be better to vote on the principle of a republic first and (assuming majority support for a republic) choose the model afterwards. So, the thinking goes, we should vote on the general principle of a Voice first and leave the Government to design the model later.

Before explaining why this is wrong, it’s worth recalling the history of the republic referendum. Although polls suggested majority support for a republic, former Prime Minister John Howard dealt with the issue by establishing a constitutional convention to come up with a proposal. The convention was dominated by “establishment” republicans, most notably Malcolm Turnbull, who wanted to replace the Governor-General with an appointed president while changing nothing else about the parliamentary system.

This proposal was defeated by a combination of monarchists and advocates of an elected president, who saw an appointed president as a permanent block to hopes for a more democratic system. Establishment republicans regarded the idea of an elected president as even worse than the monarchical status quo and came to the conclusion that a two-stage process was needed.

That sounds convincing at first hearing. But, if we accept the establishment analysis, it implies that constitutional monarchy would beat either model for a republic in a two-way race. In the jargon of voting theory, constitutional monarchy would be the Condorcet winner (named for the Marquis of Condorcet who first wrote about these problems).

While voting theorists don’t agree about much, they do agree that, in a well-designed system, a candidate or proposal that is preferred by a majority to any other proposal ought to win.

That’s what our preferential voting system mostly achieves, unlike the “first past the post” system used in the UK and U.S. And, if you accept the analysis above, the status quo would be the winner in a preferential vote. Whichever model of the republic received the least votes would be eliminated and second preferences distributed. Enough of those preferences would go to the status quo, rather than the other republican model, to provide a majority against change.

Would a two-stage process yield a better outcome? Not if voters understood the process and voted accordingly. Suppose that supporters of an appointed president recognised that they would lose in a second round. Then those who preferred the status quo to an elected president would rationally choose to vote against a republic in the first round. The only reliable way to get a republic is to design and advocate a model that can secure majority support against the status quo

Voters aren’t perfectly rational calculators. In the Brexit referendum, for example, people voted for radically inconsistent versions of Brexit (from “Singapore-on-Thames” to “socialism in one country”), all expecting that their own version would prevail. Few if any got what they were hoping for.

But, in the context of an Australian referendum, any ambiguity will be resolved by voting “No”. If there isn’t a clearly described model on offer, people will think of what they see as the worst case and vote accordingly.

A draft model will make it much more difficult for Dutton to oppose the referendum. If he rejects a sensible model outright, he will make it clear that he remains as racist as ever. If he picks holes in the proposed model, Labor can invite him to negotiate amendments. As it is, Dutton doesn’t need to take a stand either way. He can just say that he won’t support the constitutional amendment because the Government won’t say what it means.

The Government needs to show that it can produce a model that is supported by most First Nations people and that doesn’t threaten democratic government in Australia. Then it needs to commit to introducing the same model, with minor variations, while explaining that a future parliament could choose to do things differently.

Even with a draft, the task of translating general approval for the idea of a Voice into a majority of voters in a majority of states will be a difficult one. But the idea of telling people “don’t worry about the detail, just tick the ‘Yes’ box and we’ll tell you what you voted for afterwards” is never going to work.

John Quiggin is Professor of Economics at the University of Queensland. His latest book, 'Economics in Two Lessons: Why Markets Work So Well and Why They Can Fail So Badly', is out now from Princeton University Press. You can follow John on Twitter @JohnQuiggin.

Related Articles

- Indigenous Voice to Parliament a good step, but not far enough

- Albanese's Voice to Parliament referendum should be a no-brainer

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.