Progressives need to better argue the case for equity or conservatives will have more victories like in the Voice Referendum, writes Adrian McMahon.

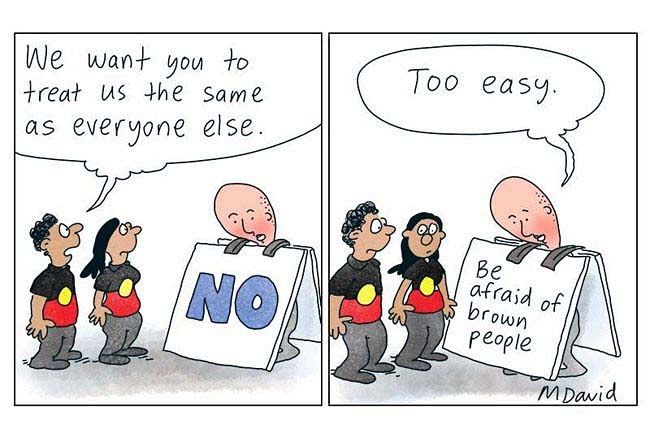

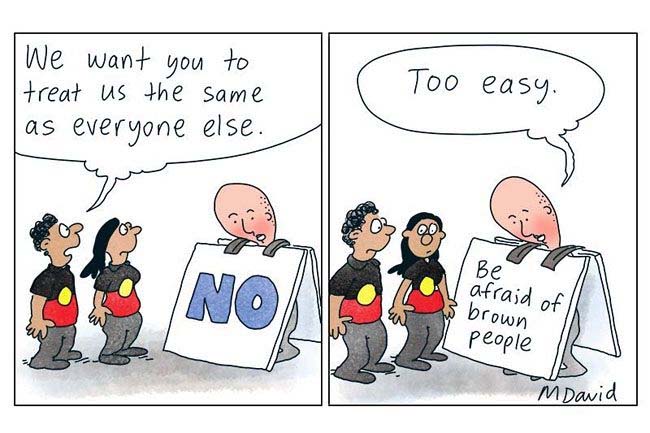

The “No” campaign’s victory in last year’s Voice to Parliament Referendum was largely based on a misleading argument but continues to serve conservatives well in various policy areas.

The conservative-led “No” campaign claimed an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice would cause division because it favoured one group of Australians over another. The “No” campaign argued that only an equal voice for all Australians would lead to an equal outcome and is therefore the fairest approach. This argument is flawed.

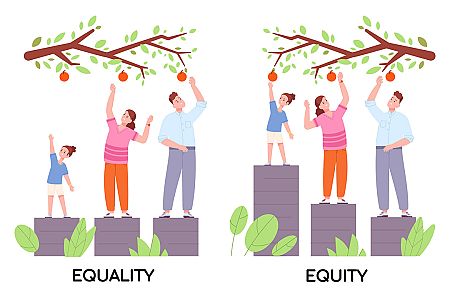

Individuals and communities in Australia do not start from an equal position, due to various factors such as gender, race, location, and levels of education and wealth. Therefore, giving them the same resources and opportunities does not lead to an equal outcome. It simply maintains the unequal status quo.

A more effective approach recognises that each individual and community has different starting positions and circumstances and as such, allocates them the resources and opportunities they need to achieve an outcome that is equal alongside all others. This is equity.

In other words, equal treatment is a sameness that continues inequality, whereas equitable treatment is a fairness that creates equality.

The image below outlines how equity is the fair means to an equal end: while the same-sized platforms result in unequal access to the apple tree, the equitable distribution of higher platforms for the woman and child means everyone can reach an apple.

Examples of equity are everywhere, such as tax and welfare systems, subsidies and grants, humanitarian and disaster relief aid, educational scholarships, pensioner discounts, women-only exercise classes, multilingual resources, closed captions television and wheelchair ramps.

On average, Indigenous Australians have long had worse outcomes than non-Indigenous Australians in areas such as health, education, employment, housing and incarceration. This has been outlined in numerous Closing the Gap reports. As such, Indigenous Australians require an equitable allocation of resources and opportunities to achieve an equal outcome alongside non-Indigenous Australians. The Voice to Parliament concept is one such example.

Division argument was key to success

Despite being a flawed argument, the conservative “No” campaign decided to claim the Voice would cause division after their focus groups informed them it would be an effective argument.

This enabled the “No” campaign to frame the Voice in the age-old division narrative of “us versus them”, where “they” (the 4% of Indigenous Australians) were receiving special rights that “we” (the 96% of non-Indigenous Australians) were not.

An Australian National University survey confirmed the tactic's success, with two-thirds of “No” voters listing “dividing the country” as the key reason behind their decision.

Census data on Australia’s 151 electorates shows “No” voters were more likely to have lower levels of formal education and income and be male, older, and living further away from city centres. As outlined below, the failure of the equity argument and the success of the division argument was most apparent in relation to voters’ levels of education and income.

Lack of education blinded voters to the equitable proposal

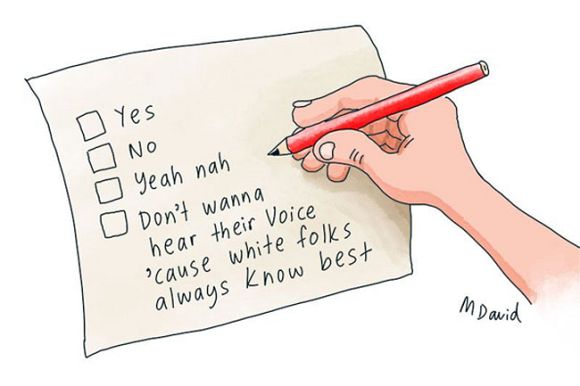

Concerning education, not only were “No” voters less likely to have a university education, but they were also less likely to be educated about Indigenous affairs.

A series of four surveys from Federation University (conducted in 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020) show that many non-Indigenous Australians are ignorant of the inequalities facing Indigenous Australians. Regarding health, education and employment, around 40% of participants across all four surveys felt Indigenous Australians were either positioned ‘about the same as other Australians’ or were ‘better off’.

Therefore, as a starting point in the Referendum, the “No” campaign benefitted from around 40% of Australians not knowing or believing the problem that the Referendum was aiming to solve. Clearly, the annual Closing the Gap reports are not reaching all Australians alike.

Winning support from voters for equitable proposals like the Voice to Parliament requires voters to know and believe that a group such as Indigenous Australians needs additional resources and opportunities. Without that foundational understanding, it is basically impossible to make the equity argument.

For those who knew about and believed in Indigenous inequality, the equity argument likely struggled because the concept of the Voice was too bureaucratic. It would not directly close the gap on issues such as health and education but act as a mechanism for community representatives to determine the best ideas to put forward to governments to enable them to introduce programs to close those gaps.

For many voters, who may not have high levels of education in civics, democracy and constitutional law, the concept was undoubtedly too complex. This was confirmed in the “No” campaign’s focus groups, which found there was voter confusion over the Voice.

Lower income makes voters susceptible to grievance

In relation to lower income voters, the “No” campaign’s division argument was likely successful because these voters felt the Referendum was not addressing their financial insecurity. Essential Media’s poll found that the less financially comfortable the voter felt, the more likely they were to vote “No”.

A separate survey conducted a week before the Referendum vote identified that the issue most Australians wanted the Government to focus on was ‘cost of living’, followed by ‘housing and interest rates’ and ‘hospitals, healthcare and ageing’.

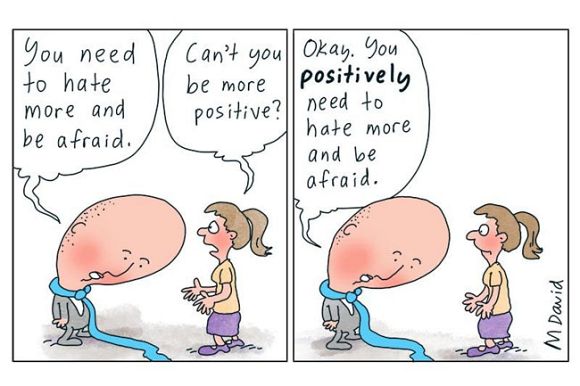

Financial insecurity is a legitimate concern for many voters, but it also makes them susceptible to the division argument that encourages grievance about “another” group receiving something they are not. The “No” campaign capitalised on this by tying it into the modern conservative and anti-establishment narrative of “the elites” helping certain sections of society at the expense of “the people”.

Progressives can win future battles on equity

The success of the “No” campaign in the Referendum guarantees that conservatives will continue to use the division argument at any opportunity. Shadow Treasurer Angus Taylor did so earlier this year when he said the decision by Woolworths to not sell Australia Day merchandise was part of “this constant desire to divide us”.

Progressives should be able to counter the flawed argument of division and win support for future equitable ideas, particularly as Australia prides itself on providing a “fair go” to all, which involves giving a helping hand to those in need.

However, the lessons from the Voice Referendum must be learnt. For equitable ideas to be supported, voters need to know and believe the problem, understand the proposed solution, and not feel that they would be disadvantaged by its implementation.

The same-sex marriage plebiscite is a successful example when 62% of voters supported the change. The problem was understood and accepted, the solution was simple, and most voters recognised they would not be affected.

Not all issues are this straightforward, but unless progressives can communicate them all clearly and simply, there will be more conservative victories like in the Voice Referendum.

Adrian McMahon has worked in the Australian and Victorian public services. He has primarily been a policy adviser in the fields of international relations and family violence.

Related Articles

- Voice Referendum doomed by Coalition's digital manipulation

- IA's last word on the Voice

- EDITORIAL: IA's last word on the Voice

- White man's dark money: Meet the No campaign bankrollers

- Black lives don't matter Down Under

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.