Institutions of learning should be shielded from the military-industrial complex drawing Australia into America's wars, writes Dr Binoy Kampmark.

WANNING SUN from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), asks in hope:

Can we still see universities as places to learn and produce knowledge that, at the risk of sounding naïve, is for the greater good of humanity, independently transient of geopolitical skirmishes?

The history of universities during the Cold War era tells us that it is precisely at such times that our government and our universities need to fight tooth and nail to preserve the precarious civil society that has taken millennia to construct.

History can be a useful, if imperfect guide, but as its teary muse, Clio, will tell you, its lessons are almost always ignored. A recent investigative report published in Declassified Australia gives us every reason to be pessimistic about Sun’s green-pastured hopes for universities untethered from compromise and corruption.

Far from preserving civil society, the Australian university sector is going the way of the U.S. model of linking university research and innovation directly to a gluttonous military-industrial complex. More importantly, these developments are very much on the terms of the U.S. imperium, in whose toxic embrace Australia finds itself.

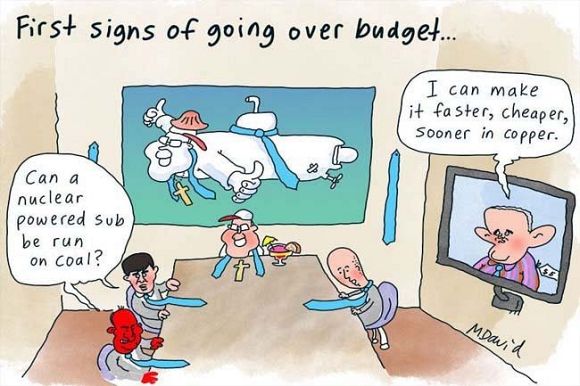

Over 17 years, the authors of the report found, U.S. defence funding to Australian universities had risen from $1.7 million in 2007 to $60 million annually by 2022. The funds in question are backing ‘research in fields of science that enhance U.S. military development and the U.S. national interest’.

To justify this effort, deskbound think tankers and money-chasing propagandists have been enlisted to sanitise what is, at heart, a debauching enterprise. Take, for example, the views of the United States Studies Centre (USSC), based at the University of Sydney, where university-military collaboration under the shoddy cover of learning and teaching is being pursued in reverie. For those lovely types, universities are ‘drivers of change within society’.

The trilateral security pact of AUKUS, an anti-China enterprise comprising Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States, has added succour to the venture, drawing in wide-eyed university administrators, military toffs and consultancy seeking politicians keen to rake in the defence-scented cash.

With salivating enthusiasm, a report by members of the USSC and the University of Nottingham from March 2024, noting the findings of a joint University of Sydney and Times Higher Education World Academic Summit, opens with a frank enlisting of the education and research sector ‘as enablers of operationalising the strategic intent around AUKUS’. No less than a propagandising effort, this will entail ‘building social license for AUKUS’ through ‘two primary inputs: (1) educating the workforce; and (2) Pillar II advanced capability research’.

This open embrace of overt militarisation entails the agreement of universities ‘across the three countries’ to ‘add value to government through strategic messaging and building social licence for AUKUS’. This is no less an attempt to inculcate and normalise what is, at heart, a warring facility in the making.

The authors admit their soiling task is a challenging one:

‘Stakeholders agree the challenge of building social licence for AUKUS is particularly acute in the Australian context, where government discourse has been constrained by the need to reestablish diplomatic relations with China.’

Diplomacy is such a trying business for those in the business of conflict.

The raw note here is that the Australian populace is ignorant of the merits of the belligerent, anti-Beijing bacchanal between Canberra, Washington and London. It is ignorant of ‘the nature of strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific and its place in Australian regional strategy for AUKUS’.

Concern is expressed about that most sensible of attitudes: a decline of popularity for the proposed and obscenely expensive acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines, costing $368 billion.

The report continues:

‘USSC’s own polling, released in late 2023, finds that support for Australia acquiring nuclear-powered submarines has fallen below majority (49 per cent).’

Such terrifying findings – at least from the USSC’s barking-mad perspective – had also been:

‘... corroborated by other major Australian polls, including the Lowy Institute and 'The Guardian', which find that support has weakened, rather than firmed since the optimal pathway announcement.’

The Australian public, it would seem, knows something these wonks don’t.

When the warmongers worry that their wares are failing to sell, peacemakers should cheer. It then falls on the warmongers to think up a strategy to reverse the trend. An imperfect, though tried method is to focus on the use of that most hideous of terms, “social licence,” to bribe the naysayers and sceptics.

The notion of “social licence”, framed in fictional, social contract terms, should propel those with a scintilla of integrity and wisdom to take arms and rage. The official literature and pamphleteering on the subject point to its benign foundations. The Ethics Centre, for instance, describes it as an informal arrangement whereby an informal licence is ‘granted to a company by various stakeholders who may be affected by the company’s activities’.

Three requirements must be accordingly satisfied in this weasel-worded effort: legitimacy, by which the organisation ‘plays by the “rules of the game”’; credibility, by which the company furnishes ‘true and clear information to the community’ and trust, by which the entity shows ‘the willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another’. These terrible fictions, as they come together, enable the veil to be placed over the unspeakable.

When the flimsy faeces encasing such a formulation are scraped away, the term becomes more sinister. Social licencing is nothing less than a tool of deceit and hoodwinking, a way for the bad to claim they are doing good and for the corrupt to claim they are clean. Polluting entities excuse what they do by suggesting that the returns for society are, more broadly speaking, weightier than the costs.

Mining industries, even as they continue to pillage the Earth’s innards, claim legitimacy for their operations as they add an ecologically friendly wash to them. We all benefit from the harm and harming, so why fuss?

To reverse this trend, a few measures should be enacted with urgent and acceptable zeal.

Purging university vice-chancellors and their simpering toadies is a healthy start.

Trimming the universities of the spreadsheeting grafters and the racketeers, percolating through departments, schools and colleges, would be another welcome measure. All are accomplices in this project to destroy the humane mission of universities, preferring, in their place, brands, diluted syllabi, compliant staff and morons for students.

All in all, a clear wall of separation between the civic goals of learning and knowledge should be built to shield students and staff from the rapacious, murderous goals of the military-industrial complex that continues to draw sustenance from deception, delusion and fear.

Dr Binoy Kampmark was a Cambridge Scholar and is a lecturer at RMIT University. You can follow Dr Kampmark on Twitter @BKampmark.

Related Articles

- Mobilising opposition to AUKUS: The Marrickville declaration

- USUKA: The hidden history of AUKUS

- 'AUKUS! AUKUS!': Beware the cry of the cuckoo

- Funding the imperium: Australia subsidises U.S. nuclear submarines

- Challenging Australia's blind allegiance to USA against China

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.