The Board of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) meets on 5 November and there seems little chance of a change in the official interest rate.

The context of this near-certain decision to hold rates steady is the 13 interest rate hikes totalling a record 425 basis points between May 2022 and November 2023, moves which make monetary policy settings ultra restrictive. In recent months, many other central banks worldwide have been slashing interest rates with glee as they react to weak growth and inflation tracking towards their respective targets.

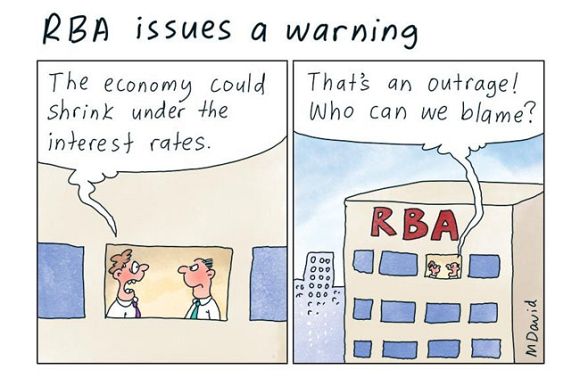

The RBA is one of the very few central banks not to start an interest rate cutting cycle and its recent rhetoric suggests there is as much chance of it hiking – yes, hiking – rates as there is in an interest rate cut.

Of course, sober and objective analysts know quite plainly that with inflation back on target, interest rates should be cut.

What is the RBA Board thinking?

One of the very good reforms delivered by Treasurer Jim Chalmers to the functioning of the RBA is the elevation of transparency and scrutiny of its operations.

Key to this is the RBA Governor’s press conference after each board meeting and the appearances of senior officials before various parliamentary committees throughout the year.

These are important opportunities for the Governor and senior staff to articulate key issues and conundrums the board is dealing with and for them to be questioned on aspects of policy, operations or readings of the economy that were often overlooked in the bad old days of limited scrutiny.

Unfortunately, many of the questions at these and other events are not all that helpful for those looking to understand what the RBA is thinking about the economy and policy options.

Indeed, there are a few really basic questions that the RBA has never been asked. They are important and the RBA should answer them, particularly in light of the recent inflation data and events overseas. The questions are all directed to the endpoint big question: “Why are you not cutting interest rates?”

Below is a list of very basic questions that the RBA should be asked.

Questions for the RBA

The questions below focus on facts. They also recall that the mandate of the RBA is to have inflation around the mid-point of the 2-3% range and for the economy to run at full employment.

Specifically, ‘the Reserve Bank Board’s role within this is to focus on achieving sustained full employment, which is the current maximum level of employment that is consistent with low and stable inflation’.

Here are the questions for the RBA.

Q: Can you confirm that in the December 2023 agreement on monetary policy, the objectives of the RBA are: The appropriate goal is ‘consumer price inflation between 2 and 3 per cent’. Further, ‘The Reserve Bank Board sets monetary policy such that inflation is expected to return to the midpoint of the target’.

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: Can you confirm that based on the monthly data for September, annual inflation is 2.1%?

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: Based on the September quarter data, annual inflation is 2.8%?

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: Whether it is the monthly or quarterly data, is annual inflation within the RBA target range?

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: Can you confirm the unemployment rate has risen from a low of 3.5% during 2023 to the current 4.1%?

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: With the current profile for economic growth, do you expect the unemployment rate to increase further?

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: Can you confirm that the last three quarterly readings for the wage price index are, respectively, 1.2%, 1.0% and 0.8%, with the rate of growth decelerating?

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: With the unemployment rate increasing, do you expect wage growth to slow over the next year?

A: Hint: Yes.

Q: With wage growth easing under the current economic circumstances, is it possible that the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) is around 4% and if so, why are you aiming to drive unemployment higher than this?

A: Hint: We are not sure. It could be, but we don’t know. We will only know well after wage growth slows and inflation falls.

Q: Can you indicate anywhere in the Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy a reference to “trimmed mean” or “underlying” inflation?

A: Hint: No.

This simple type of Q and A for the RBA Governor and her board can lead to one conclusion — interest rates are too high and need to be cut.

It is making up reasons why it will not cut, talking about trimmed mean or services inflation but strangely, not good inflation which is 1.4% or when items such as tobacco, insurance and education are excluded from the headline result, inflation is under 2%. And these items are driven more by government policy and climate change than the level of interest rates.

As things stand for the RBA, targets have been hit and by being pig-headed on interest rates and its interpretation of inflation, there is a risk of an unnecessary and undesirable overshoot and the way to guard against this is lower interest rates.

It remains a mystery why the RBA analysis is so far skewed away from reality as it keeps open the option of hiking interest rates at worst, but almost equally badly, keeping them too high for too long.

What would the RBA say?

In more detailed answers to these questions, the RBA would almost certainly note that the sharp inflation fall was heavily influenced by the electricity subsidies and therefore should be discounted. And to be sure, this is a relevant, albeit low-tier, consideration.

When hiking interest rates, the RBA all but ignored the items whose prices were rising sharply due to factors outside the control of interest rates — tobacco, insurance, health care, school and education fees and, to some extent, dwelling rent.

All of this is a bit silly because over time, when the difference between the headline and trimmed inflation rates wash out, the gap between the two measures of inflation is zero.

In the end, the RBA is meeting its objectives, which is great news.

Why it is putting this achievement at risk by keeping interest rates too high for too long is an issue that requires close scrutiny.

Stephen Koukoulas is an IA columnist and one of Australia’s leading economic visionaries, past Chief Economist of Citibank and Senior Economic Advisor to the Prime Minister.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- RBA deputy governor hits a few prophets for six

- Interest rate cuts around the world — Australia should join the gang

- Reserve Bank playing with fire — beware of the creeping recession

- Unemployment — the forgotten target of the RBA

- RBA's next interest rate move likely to be a cut