The Migration Act has become a fest of discrimination, deteriorating rapidly under the Abbott and Morrison Governments.

There was a litany of amendments to the legislation that current Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, managed to pass in late 2014.

As Immigration Minister, Morrison toughened up the Character and General Visa Cancellation Bill, mangling a “character test” contained in Section 501 of the Migration Act 1958, so “non-citizens” can be deported if sentenced to at least 12 months prison time. This disregarded the fact of penance served, denying the clean slate and the redemptive — searing Australia as a compassionless society.

Hence, thousands of long-term residents – the majority New Zealanders – were deported and families were devastated.

A few years ago, I prevented the ludicrous deportation effort of a First Nations father-of-four.

According to former Immigration Minister, MP David Coleman, on introducing the 2014 amendments:

“Entry and stay in Australia by noncitizens is a privilege, not a right, and the Australian community expects that the Australian Government can and should refuse entry to non-citizens, or cancel their visas if they do not abide by the rule of law.”

The changes widened the net of the presumptive character test to the deportation of non-citizens on being sentenced to at least 12 months incarceration from the pre-existing 12 months. Section 501 is a human rights abuse.

Subsection 501(6) contains the character test. It provides the power to deport if the minister just “reasonably suspects” a non-citizen doesn’t pass it. What is “reasonably suspects”?

The Morrison Government – with its lie of being steeped in redemptorist Christianity – has expelled increasing numbers of people from Australia.

Once again, the Morrison Government, via Immigration Minister Alex Hawke, introduced further inhumanity with the Migration Amendment (Strengthening the Character Test) Bill 2021 last November. People are automatically deported on being convicted of certain “designated crimes”, despite the length of the sentence.

The Morrison Government is the most classist and racist Government in my living experience. It is also the most elitist, winding back civil liberties and eroding rudimentary human rights.

A federal human rights act is urgently needed, one which must protect the rights of all citizens and all residents.

A human rights act commits governments to the common good. The work of government becomes clearer and monitored where there is a human rights act.

During the last decade, I have been representing or assisting residents of many years, mostly individuals who have Australian born and bred children, who had their visas revoked and hence at imminent threat of deportation. Relatively unaccountable bureaucrats and politicians bent by muddled-minded dogma play out age-old racism and classism, revoking visas, blindly following presumptive protocols which have been haphazardly enmeshed in the Migration Act.

Discriminatorily, it is the impoverished who are mostly at risk if they were born overseas, despite living most of their life in Australia. The majority are unrepresented before tribunals and courts — and as a nation, we should be ashamed of this hideous reprehension.

Every human being should be protected in terms of their rudimentary human rights. Australia’s human rights record, on so many fronts, has degenerated contextually to its lowest ebb during the last quarter-century. A federal human rights act can repair Australia’s appalling record of human rights abuses. But we are a long way from this prospect, as the evident immoral morass of present-day political ill-will describes elitism, fortress Australia, classism and racism.

Human rights and civil and political liberties should never be at the behest of any government but rather by referenda to the people. The Migration Act has become an international disgrace, condemned by the United Nations. Only reforms to the Australian Constitution or a robust federal human rights act can protect us from narrow-minded politicians domesticating discrimination into legislation.

The social good, the common good and universality should never be tenuous or frail because of a change of government. Without a human rights act, we are at risk of tyranny by government.

Last December, I attended an appeals tribunal to represent, advocate and hopefully arbitrate the right of a long-term Australian resident to be released from an immigration detention centre. I argued that he should not be deported. He and his family should not be separated. I had tried to secure him a lawyer, but everyone advised the case could not be won or was unlikely. I was saddened for his family. Just prior to Christmas, the tribunal judge ruled in our favour and the Commonwealth’s cancellation of his visa was revoked.

We were five hours in the tribunal fighting for dear life. I argued no family should be effectively dissolved. The argument of “bad character” is, in fact, presumptive. When a carceral sentence is completed, penance is complete and the redemptorist in all of us should prevail — it’s a clean slate. To argue otherwise is to defy the legal proposition of penance as served and in fact, plays out as if ex-judicial. This is where we must draw the line, separating governments from courts and tribunals.

Suicidality is sky-high among separated families. I argued it is a classist narrative for any government to insist on separating families because of presumptive bad character assumptions. The obvious impacts are harrowing for children of fathers and mothers deported, and for the deportees to a faraway land to which they have lost ties or never actually had any ties, other than the fact of their birth.

A few years ago, I prevented the ludicrous deportation effort of a First Nations father of four. His Australian First Nations parents had spent two years in New Zealand, where he was born. This is how insane the looseness of some of the sections are, of the Migration Act.

I argued that, in fact, the law does not argue mandatorily for deportation. Indeed, it is deficits in the law allowing for bureaucrats, including the Minister of Immigration, to discriminate against people.

At all times, a completed carceral sentence means the opportunity for the redemptive and restorative — never does it, or should it mean, furthered punishment.

I won the December case for a father of three children, all Australian born and bred. He has been in Australia since he was ten, near three decades. His parents had become Australian citizens and so, too, his siblings. He had no one in the Philippines. I did not expect a favourable court ruling. I was relieved. The individual was ecstatic. But what about all the invisible others?

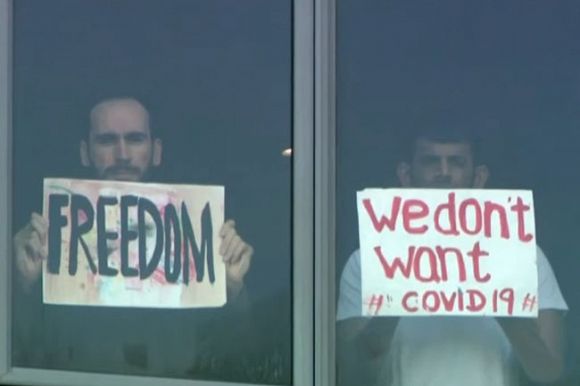

Since the favourable court ruling, I have been inundated with requests from individuals slated for deportation, languishing in immigration detention centres, begging for me to represent them. I can’t manage the volume, it’s impossible, although I am assisting as many as I can with their representations. There are several I have assisted. We are awaiting rulings.

The Migration Act 1958, Section 501 needs to be overhauled. It imputes natural justice but when people are not represented, this amounts surely to natural justice denied. It is a human rights abuse — especially when the near majority of the at-risk are individuals who have endured disadvantage and hardships from the beginning of life, who were born into poverty and marginalisation, who would not complete secondary schooling.

According to Section 501, the Minister for Immigration or a delegate can cancel the visa of someone on a “character test”. Should a minister have this right? A character test is always a subjective moral proposition and should not be interpretatively intertwined as a legal proposition, particularly when penance has been served. Only a compassionless society would domesticate protocols to deport individuals despite penance served.

The character test is loosely defined by Subsection (6). The Minister may cancel a visa even on “reasonable suspicion” one does not pass the character test. The Minister may cancel a visa if a person does not pass the character test. The “character test” is presumptive on a ‘substantial criminal record’ but individuals with single carceral sentences have been deported and others without criminal convictions have been deported.

More than 500,000 Australians living – one in 50 Australians – have been to gaol. If they had been born overseas, even if their parents were Australian born, they could be deported. What sort of global citizen is Australia to dump people overseas?

The whole Government needs to be held to account. Under Subsection (3), the Minister must cause notice of the making of the decision to deport an individual to be laid before the House of the Parliament within 15 sitting days of the House after the day the decision was made. The exception is anyone falling foul of the ASIO Act.

The collective parliamentary silence is deafening and indicts every parliamentarian. Where are the outcries? Deportations can’t be argued as “absolutely” Kafkaesque when in effect, there is an obscene multi-partisan quiet — in fact, complicity.

For the purpose of this article, I am focusing on residents with families and residents who have served their court-ordered carceral sentences and who are not a threat to any substantive national interest.

But everyone should be availed substantive legal representation. Where this is not the case, it’s an arguable denial of natural justice and a diminution of judicial fairness. But for those I describe as living their lives as Australian bred, they must not be deported. Where there is criminal offending, their penance is to be served in an Australian context and never cumulatively compounded by deportation — in my reckoning, it’s a human rights violation and a moral abomination.

The incumbent Government is discriminatory and tough on people policies, cultivating hate incitement and nurturing divides instead of contextualising ways forward, instead of coalescing a diverse human family.

A federal human rights act is urgently needed but one which must protect the rights, make impermissible the Kafkaesque, for all citizens and all residents — special visa residents, permanent and temporary visa residents, refugees and asylum seekers. No one who walks this continent, no matter where they are from, should ever become unseen and unheard.

A decade ago, I fought for up to 158 Indonesian children – the majority incarcerated in Australian adult prisons – while the remainder languished in squalid immigration detention centres littered across the continent. This abomination should never have occurred in Australia, but it did.

This is what happens when we have no robust bill of rights. This is what occurs when we have racists and classists for parliamentarians. This is what occurs when bills and amendments to legislation are rushed through parliaments – federal, state and territory – with little or zero public scrutiny.

No government should be unaccountable. A human rights act commits governments to the common good. A comprehensive robust human rights act ensures a higher level of trust from the people than is the case with the absence of one.

Increasingly, during the last three decades, our Federal Government has become increasingly less accountable. The invisible must be made visible. For everyone we are representing in tribunals, scores are unrepresented, the majority are deported and families and children are decimated.

The Australian Senate needs an education. The Australian nation needs to know. We must carry hearts and souls to the truth. Once in the know, the Australian people and the media can galvanise governments to do what is right — the common good, understand human rights as universal.

I fight for as many as I can because I remember those who took their lives rather than be deported. A few years ago, a 22-year-old former Iraqi refugee was to be deported. He was a young father of two living in Sydney. For alleged minor offences, he was detained at Villawood Immigration Detention Centre.

One night, he was flown across the continent, away from family to Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre. He wasn't supported and died by suicide. The detainees burnt Yongah Hill. I assisted the grief-stricken family. I organised their legal representation. They are suing the Commonwealth Government. But this will never bring back the young father — a life needlessly lost because of cruel policies.

If there’s a Heaven, the so-called Christian-faith-based members of the Morrison Government will have a lot of explaining to do or be purgatory-bound.

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus. He is the national coordinator of the National Suicide Prevention & Trauma Recovery Project (NSPTRP). You can follow Gerry on Twitter @GerryGeorgatos.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.