Universities should encourage overseas students to do courses in health and education, and TAFEs should offer overseas students more traditional trade courses, writes Dr Abul Rizvi.

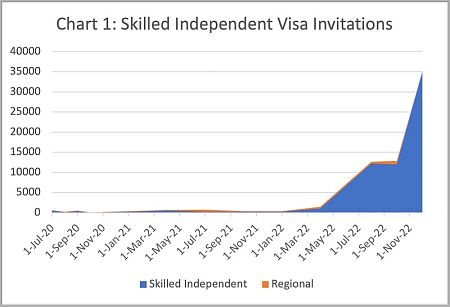

IN DECEMBER 2022, the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) issued an astonishing 35,000 invitations (both to offshore and onshore applicants) for the skilled independent visa (Subclass 189). This is the points-tested visa that most distinguishes Australia as a migrant settler nation and is most often the focus of overseas students.

But why would it do that after two earlier invitation rounds this program year of 12,200 invitations on 22 August 2022 and 11,982 invitations on 6 October 2022 (see chart below)?

This means that in 2022-23, DHA has now issued 59,182 invitations for the skilled independent visa against a planning level of just 32,100. Not only is that 27,082 more invitations than the planning level – noting the planning level counts both primary and secondary applicants – but also more invitations than visas granted in this category in any previous year.

Three possible explanations

Firstly, it may be that DHA is concerned it will not be able to deliver the planning levels in other parts of the skill stream and is trying to make up for that with a larger skilled independent category.

Secondly, it could be that the minister has decided to reduce the number of places in other skill stream visa categories such as the Global Talent Independent Program or the Business Innovation and Investment Program (BIIP) because of policy concerns with these visas.

The Government has also announced it has ceased accepting new applications for the New Zealand citizen portion of the skilled independent visa pending a review of policy in this space. This may be linked to further negotiations with the New Zealand Government for additional places to accept people who arrived by boat after re-introducing offshore processing in 2013.

Or thirdly, perhaps a large portion of the invitations are not converting to visa grants because:

- the claims made in the initial Expression of Interest (EOI) could not be validated and the applications had to be refused;

- some claims in EOIs have expired; and

- possibly, some EOIs have already been nominated by a state/territory government.

The last of these explanations seems most likely, with possibly a very large percentage of invitations not converting to a visa grant. In the past, the portion of invitations that did not convert to grants was relatively small.

That means a much larger portion of processing resources are being used to deal with applications that are being refused — as is also now the case with offshore student visa applications and due to abuse of the onshore asylum system.

This is at a time when DHA is being pressed by ministers to clear the massive visa application backlogs that the new Government inherited. From an efficiency perspective, very high refusal rates reflect wasted resources possibly due to poor visa design and/or poor administration.

Implications for State/Territory-Nominated Visas

Having issued 59,182 invitations in the skilled independent category to people who lodged an EOI up to and including November 2022, the pressure will now be on state/territory governments to source their visa nominations from the same pool of EOIs — the Commonwealth’s actions will make it more difficult for state/territory governments to meet their record allocations in 2022-23.

It should be noted that potential migrants will almost always prefer a skilled independent Subclass 189 visa over a state-nominated visa because of the greater flexibility the skilled independent visa provides.

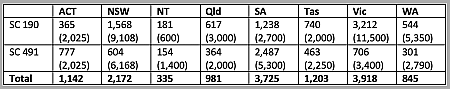

Total allocations for state/territory governments in 2022-23 are 36,283 places for the Subclass 190 direct permanent residence visa and another 25,333 places for the Subclass 491 provisional visa. Both visa types will be counted against the 2022-23 Migration Program target of 195,000.

To end of November 2022, state/territory governments had made only 8,465 nominations in Subclass 190 (that is, 23.3 per cent) and 5,847 nominations in Subclass 491 (that is, 23.1 per cent). On this basis, it would appear state/territory governments may struggle to meet their allocations.

Many are making significant efforts to attract more interest in migrating to their jurisdictions. It is likely these efforts may get more frantic during the first half of 2023. DHA will need to be ready to manage a very large number of state/territory government nominations during that period, including by transferring resources from processing other visa types.

Implications for Overseas Students

As usual, the key will be overseas students.

While lobby group Universities Australia is correct to recognise this fact, its analysis in this article largely misses the point.

While improvements certainly need to be made to visa design, the real issues which Universities Australia happily ignores are:

- Too many overseas students are undertaking courses that are not relevant to Australia’s long-term needs but more suited to what universities want to deliver (for example, courses in finance or business often because these are low cost but high profit). There are not nearly enough overseas students who have undertaken courses in occupations in high demand, particularly in health and education but also in the traditional trades — which is of course an issue for TAFE and the construction industry.

- Overseas students are struggling to get skilled jobs that get them the requisite skilled work experience to put them on the pathway to permanent residence. This is despite the current tight labour market. Universities must do better in helping overseas students secure skilled jobs and communicating the benefits of employing overseas students to Australian employers. Or are universities recruiting students without sufficient aptitude for the courses they are doing simply because they are prepared to pay the requisite fees?

- The very high number of offshore student visa applications being refused by DHA (partly due to concerns about fraud) is something universities also need to reflect on — particularly if they are recruiting students more interested in work rights than study. Managing the return to restricted work rights from 1 July 2023 should also be a focus for universities.

Fixing this should be a key priority for the Parkinson-led review of the migration system scheduled to report in February 2023.

But universities can help by facing up to the issues they can address so that they do indeed attract the best students.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.