The Federal Government's pandemic strategy has been a series of mistakes that could have easily been prevented, writes Dr Kim Sawyer.

FOR YEARS, I have observed the failure of Australian policymakers. Alternative voices not heard, policies put on the back shelf, recommendations not enabled. The signature of political failure.

In 1994-1995, I appeared before two senate committees on public interest whistleblowing. The committees made 55 recommendations, one of which to establish a federal public interest disclosure agency — a Federal ICAC. It never happened. None of the other recommendations ever happened. It took 20 years for federal whistleblowing legislation.

It is the same in other areas. In 2001, I appeared before a senate committee on universities. The committee unanimously recommended the establishment of a universities ombudsman. It never happened.

We seldom elect politicians with the foresight to govern for the future rather than the past. Politicians are too addicted to the 24-hour news cycle and popularity to govern for the future. Necessary policies are enacted too little and too late, whether for climate change or corruption.

The pandemic has amplified the problem. Australia’s pandemic plan was never really a plan. It was policy on the run driven by a treadmill of models and projections, rather than foresight.

There were three mistakes. The first was not to recognise the importance of ventilation. We only had to look at SARS to see what we had to do. Quarantine people in purpose-built facilities where windows could open. Establish a purpose-built hospital where the windows could open.

As I wrote often, SARS provided the answer in Vietnam. A story of two hospitals, one air conditioned with closed windows, the other opening windows. The one with opening windows had no infections.

The second mistake was testing. In March 2020, I wrote that we needed to test across the population, to find the spreaders before they spread. The reason we had to do that was because so many of the infected had no symptoms or only mild symptoms. The only way we could mass test was to use rapid tests.

Unfortunately, we put all our eggs into the basket of one test — the PCR test. That was a mistake. The PCR test is the most accurate test in a window of five to 15 days after infection, but it is not suitable for mass testing. The use of PCR tests generated long queues at testing stations, long delays in processing results and excessive disruptions to daily lives.

For most of the pandemic, nearly 99 per cent of the test results were negative. We wasted many resources on the uninfected. Instead, we could have developed a rapid antigen test strategy as early as 2020.

In the first half of 2020, rapid antigen tests were being developed by Australian companies, but they were excluded from the policy table. Pathology groups dominated policy making. Pathology companies extracted monopoly profits. They increased the price of the test from $25 to $100 and got the Government to pay.

Rapid antigen tests could have been produced as early as July 2020 at a cost of $10-15 — a fraction of PCR tests. Why then were they not approved? Billions of tests could have been manufactured, yet the Government chose to ignore rapid test manufacturers and continue with the long queues, long delays and high costs of PCR tests.

The arrival of Omicron revealed the flaw in the strategy. Omicron is so transmissible that nearly everyone will have to be tested. The only answer is rapid testing. We have now adopted the testing strategy that could have been adopted 18 months ago. The failure to listen to alternative opinion led to the existing shortages in rapid test kits. We failed to see what we needed to see.

The third mistake was in the vaccination program. Australia has spent $8 billion on vaccines, but we got the timing wrong. We secured 54 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, including 50 million to be manufactured locally. AstraZeneca was first approved by the Therapeutic Goods Authority on 15 February 2021, when it had been approved in the UK six weeks earlier.

A vaccination program could have occurred in the first half of 2021 in anticipation of an expected winter wave of the virus. Yet by September, only one-third of the population over 16 had been fully vaccinated. We vaccinated too late for the arrival of Delta.

Similarly, we knew that the Omicron variant would arrive here in December. We could have fast tracked the booster program and not closed the vaccination centres over the Christmas-new year period. We could have reduced the time between the second and third doses earlier. We failed to anticipate what could have been anticipated.

The vaccination program had to be accompanied by education explaining vaccines, the risks and benefits, and that to vaccinate is to protect not only oneself but also the person next to you. The failure to educate was costly for the AstraZeneca vaccine. Risks of blood clots associated with the vaccine were greatly exaggerated when the risk of clots associated with COVID-19 was ten times higher.

The cost was vaccine hesitancy. By October, the unused AstraZeneca vaccine stockpile was more than 7 million doses. Australia had an opportunity not only to vaccinate our own population, but also to supply vaccines to countries that could not afford the vaccines. We wasted our advantage.

I have repeatedly witnessed the failure of policymakers to anticipate what could be anticipated. Perhaps the pandemic will be our wake-up call, but we will need a different breed of politician.

Dr Kim Sawyer is a senior fellow in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne.

Related Articles

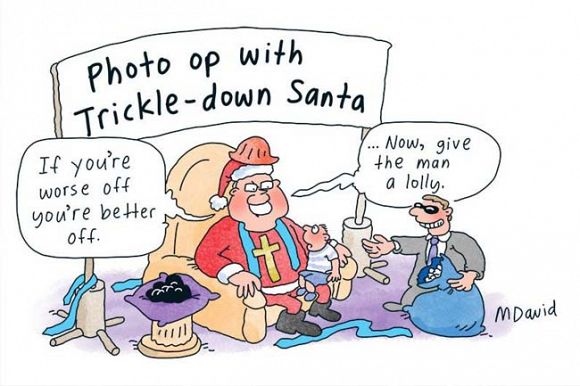

- Government's COVID Christmas plan was capitalism at its worst

- NSW Government slammed as COVID cases soar

- School safety neglected as COVID-19 infections rise

- COVID-19 is a race and our children are left at the starting line

- Returning to the office post-COVID: It's not set in concrete

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.