If history offers useful guidance, British voters should soon change their government, Alan Austin reports.

THE PEOPLE of the United Kingdom will decide in five weeks whether to continue to be governed by the Conservative Party, which has managed the nation for the last 14 years.

Commentators have opined that the decision will be made on the economy.

If so, does this bode better for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s incumbents or the Labour Opposition led by Sir Keir Starmer?

Voters can now compare the Conservatives’ economic outcomes with those of the Labour Administration, which governed from May 1997 to May 2010. Unlike many Europeans, the British favour long-term governments. Through the last 14 Tory years, Denmark, Belgium and Israel have had four different governments. Austria, Finland and Iceland have had five. Italy and Greece have had seven.

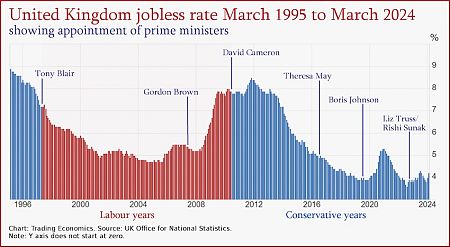

Jobless over the journey

One key variable is the jobless rate. This reached a post-war peak of 11.9% in 1984 during the disastrous Thatcher years.

It remained high throughout the Tory rule, having declined only to 7.3% when they lost office in May 1997.

Incoming Labour PM Tony Blair got the jobless below 5% for most of the period between January 2001 and December 2005. It surged during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 to peak at 8.5% at the end of 2011. It only returned below 5% again in late 2016.

Economic growth

In the last 30 years, Britain’s annual growth of gross domestic product (GDP) has been consistently positive but very low. For most of the first ten Tory years – from 2010 to 2019, pre-COVID – GDP growth fluctuated between 1.0% and 3.3%.

This was much lower than in the prior Labour period, when it ranged between 1.6% and 5.1%, excluding the six aberrant negative quarters during the GFC.

The strongest period was from 1997 to 2000, when annual growth was higher than 4% for nine quarters and above 5% for four of them.

Budget deficits

For most of British history since 1951, the economy has generated low budget deficits. Exceptions to this were a surplus of 1.7% of GDP in 1969, a 1% surplus in 1988 and three more modest surpluses from 1998 to 2000.

In retrospect, Tony Blair's decade from 1998 to 2007 was the best period for budget management, given that balanced budgets are desirable over the long term.

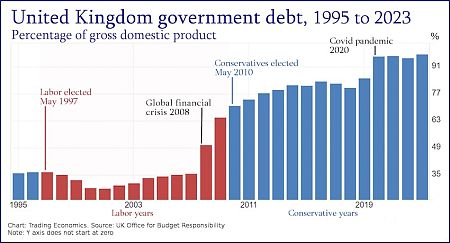

Government debt

Britain stacked on hefty government debt during the Second World War, as did every combatant nation, including Australia, New Zealand and the USA.

This had fallen below 200% of GDP by 1950, below 100% in 1961, below 50% in 1972 and to a post-war low of 21.6% of GDP in 1990.

From 1991 until the GFC whacked the world in 2008, debt ranged between 22% and 37% of GDP.

At those levels, the UK was then a low-debt economy. Borrowings were just 28.3% of GDP in 2000. All other G7 countries had much higher levels that year. The USA, Germany and France were above 55%; Canada above 80%; Italy and Japan above 100%.

The best period for debt management was again the Tony Blair years. Debt was 36.6% of GDP when he took office and 35.1% when he left. Borrowings subsequently increased through the GFC and have not yet subsided.

Debt increased disastrously under the Tories, from 64.7% of GDP when they took office in 2010 to 97.6% at the end of last year, the highest since 1962. This is by far Europe’s worst recent debt blow-out. They deserve to lose office just on that statistic alone.

Impact of Brexit

It is difficult to argue that Brexit has impacted the economy, positively or negatively. This is because the formal separation from the European Union in February 2020 coincided with the onset of the pandemic.

Exports fell sharply for the next four months, then resumed their long-term growth. By November 2021, exports were back to pre-COVID-19 levels and have continued to rise since.

Similarly, the brief surge in the jobless in early 2020, as shown in the above chart, is more likely due to COVID than Brexit.

Inflation actually declined from 1.8% in January 2020 to below 1% for most of 2020 and early 2021.

Best global rankings

Looking at all variables, the British economy performed best relative to both its own history and the rest of the world between 2001 and 2007, when Tony Blair was PM and Gordon Brown managed the economy.

This mirrors the experience of reformist administrations in Australia, New Zealand, the USA, and elsewhere. Governments that prioritise the majority of low-income earners generate better overall outcomes than those that serve corporations and the rich.

Media manipulation

As in Australia, most Brits were prevented from seeing Labour’s achievements and the Conservatives’ failures by the mendacious Murdoch-dominated news media.

In September 2003, The Sun – which was then Britain’s most popular tabloid – attacked Labour with the headline: ‘Last rites: blundertaker Blair is set to bury our nation’.

This signalled the end of Rupert Murdoch’s earlier support for Tony Blair. The media then lied about the incoming Conservative Government, failing to report the steady economic decline.

This was confirmed by Lord Justice Leveson in his 2012 report into the criminal misconduct of the Murdoch media.

He found:

‘... legitimate perceptions and concerns that politicians and the press have traded power and influence in ways which are contrary to the public interest and out of public sight.'

Looking ahead

National elections will be held on 4 July. If voters base their decision on the facts, Labour should win.

If history repeats, the economy will then improve markedly and the media will conceal Labour’s successes. We shall soon see.

Alan Austin is an Independent Australia columnist and freelance journalist. You can follow him on Twitter @alanaustin001.

Related Articles

- This Week on IA: Do Elections Matter?

- Australia (and others) proving again that elections do lead to actual change

- Kids now don’t want to vote (and other fun facts about Australian elections)

- Partisan media, incoherent Labor and the rabble clings to power

- Election 2019: Post mortems reveal what happened is no mystery

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.