Dealing with the backlog of people stuck on bridging visas has to be part of the plan to reduce migration, but politicians don't see the link, writes Dr Abul Rizvi.

IT IS VERY RARE for our politicians or media to talk about the number of people on bridging visas. Yet they are the most important barometer of the health of the visa system.

With well over 300,000 people currently on bridging visas, our visa system is in poor health but our politicians have no interest in addressing this.

What is a bridging visa?

There are broadly two groups of bridging visas (BVs). First are BVs that are granted because the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) was unable to process an onshore visa application before the substantive visa that the applicant was on expired (BV A, B and C). The second group are essentially people whose substantive visas have expired but have been granted a BV while they make arrangements to depart or people who can’t readily be removed but cannot be kept in detention (BV Es and Removal Pending BVs).

When the concept of BVs was first established in the early 1990s (essentially in conjunction with the universal visa system and mandatory detention to minimise the number of people who would otherwise have to be taken into detention), we expected that no more than 10,000 or so people would at any time be on a BV. Any more than that would reflect a substantial loss of visa control.

Surge in BV holders

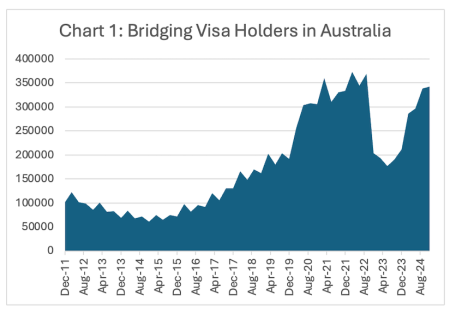

That idea has long been abandoned as the number of people on BVs rocketed past 100,000 around the time of the Global Financial Crisis. Then past 200,000 and on its way to 300,000 as Home Affairs minister at the time, Peter Dutton and his secretary Mike Pezzullo reduced visa processing and immigration compliance resources and introduced an array of bizarre visa design changes. The impact of Dutton and Pezzullo on our visa system is highlighted in Chart 1 below. The administrative incompetence was astonishing.

The huge increase was driven largely by onshore student applications, asylum seekers and partner applicants. The number of people on BVs peaked in March 2022 at over 373,000. Rather than using the opportunity of closed international borders to clean up the visa system, Dutton’s successors and Pezzullo largely sat on their hands on this issue.

The new Labor Government initially tried to clean up the mess by processing people on BVs more quickly. Initially, the number of people on BVs declined sharply to under 200,000. But faster processing is not enough. It also requires significant reform of visa design. While the Labor Government made some improvements to visa design, these were not enough and the BV backlog has boomed again to over 342,000 at the end of December 2024.

Composition of the BV backlog

The main components of the backlog (as far as BV A, B and C are concerned) at the end of December 2024 were 109,122 onshore student visa applicants, which have increased from a low of 15,065 at the end of December 2022.

With a surge of onshore student applications in February/March 2025, the student portion of the bridging visa backlog is likely to rise in April/May. Note this means the overall number of students in Australia would now be approaching 850,000. Note that students are now increasingly on BVs while they appeal refusal of their onshore student visa application to the Administrative Review Tribunal.

That backlog is now approaching 25,000.

Permanent family visa applicants part of the bridging visa backlog have continued to rise from 38,076 at the end of June 2022 to 61,856 at the end of December 2024. These are likely to be a mixture of parent and partner applications, noting the rapid rise in the overall partner backlog, which may now be approaching 90,000.

Skill stream permanent visa applicants stuck in the bridging visa backlog have remained relatively stable at around 30,000 to 40,000.

Skilled temporary entry applicants on bridging visas have increased from a low of 3,038 at the end of September 2023 to 24,003 at the end of December 2024. This reflects the strong overall demand for these visas due to a strong labour market and in particular onshore demand from temporary graduates. This trend is likely to continue, given the large stock of temporary graduates in Australia.

Temporary resident (other employment) applicants in the bridging visa backlog declined from 114,458 at the end of June 2022 to 6,012 by the end of June 2023 but then increased to 20,942 at the end of December 2024. The initial decline likely reflects the surge in applications for the COVID visa being cleared with many of these people subsequently applying for onshore student visas.

Applicants for visitor visas in the bridging visa backlog declined from 16,235 at the end of September 2022 to 890 by the end of March 2023 and then increased to 4,866 at the end of December 2024. This likely reflects backlog clearance and then an inability to keep up with demand.

Applicants for working holidaymaker (WHM) visas in the bridging visa backlog declined from 4,419 at the end of June 2022 to 119 by the end of June 2023, before rising to 4,241 at the end of December 2024. The bulk of these would be WHMs applying onshore for second and third WHM visas.

In addition, there will be a substantial number of asylum seekers in the BV backlog, possibly in excess of 70,000.

Where to now?

The lesson from the experience of the last decade is that getting the BV backlog down to an acceptable level (ideally much less than 100,000) will require not just additional visa processing and immigration compliance resources but also significant reform of student and other temporary entry visas.

Dealing with the BV backlog also has to be part of reducing net migration. Sadly, neither major party has indicated any intention to address the BV backlog, even though both say they want to reduce net migration.

Perhaps they don’t see the link?

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.