As I've become a recent columnist for Independent Australia, I thought it would be worthwhile to consider what independence means and how it relates to Australian politics.

The central tenet of independence is that we should decide for ourselves what issues concern us as Australians. That doesn’t imply either that everything should be decided centrally, overriding local and particular concerns, or that we should not act co-operatively with the world as a whole in dealing with global issues such as climate change.

It does, however, mean that we should seek to protect our political processes from interference by those who have no legitimate role to play.

The drafters of the Constitution, seeking to establish Australia as an independent nation, addressed this problem. Unfortunately, thanks to the "strict literalist" approach adopted by the High Court of Australia, their efforts have made us more, rather than less, vulnerable to the whims and potential malice of foreign governments. At the same time, developments unforeseen by the founders have made our Parliament almost the plaything of (mostly foreign) corporations.

Under Section 44 of the Constitution, anyone:

Under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, or is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or a citizen of a foreign power [is ineligible to be elected to Parliament].

For most of our history, it was assumed that anyone who was born in Australia, or had renounced foreign citizenship when naturalised and who had not sought the ‘rights or privileges of a subject or a citizen of a foreign power’ was therefore eligible. Effectively, this allowed nearly all Australian citizens to stand for office, as would be expected in a free and independent country.

This position has been reversed in a series of increasingly absurd rulings from the High Court. As matters stand at present, anyone who might be entitled to foreign citizenship is ineligible for stand for office, even if they have lived their whole lives in Australia and have no knowledge of their entitlement. The number of people affected, as Justice Michael Kirby noted in an early dissent from this nonsense, runs into the millions.

Worse still, it is not sufficient to renounce foreign citizenship. Rather, the foreign government in question must be begged to release their subject. If, as has happened in numerous recent cases, the foreign government drags its feet, our democratic processes are subverted.

So far, it would appear that these cases only involve an understandable lack of interest in promoting Australian democracy. But there is nothing to stop foreign governments from going further, for example, by expediting the cases of "friendly" candidates and delaying others.

Supposing, for example, an advocate of democracy in Hong Kong moved here, became naturalised and that they (or even their Australian-born children) sought to stand for Parliament. Is it likely that the government in Hong Kong or Beijing would rush to help them?

While the absurd theatre of Section 44 cases continues, the reality is that a large proportion of the Parliament is in fact 'under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power'. In a few cases, this power is a national government such as that of China.

But the real power in the world today is that of global corporations and financial institutions. These powers do not need to pay politicians to do their bidding. It is now well understood that anyone who follows the dictates of the corporate sector can expect a post-politics sinecure paying far more than the mere or even the $350,000 received by Ministers.

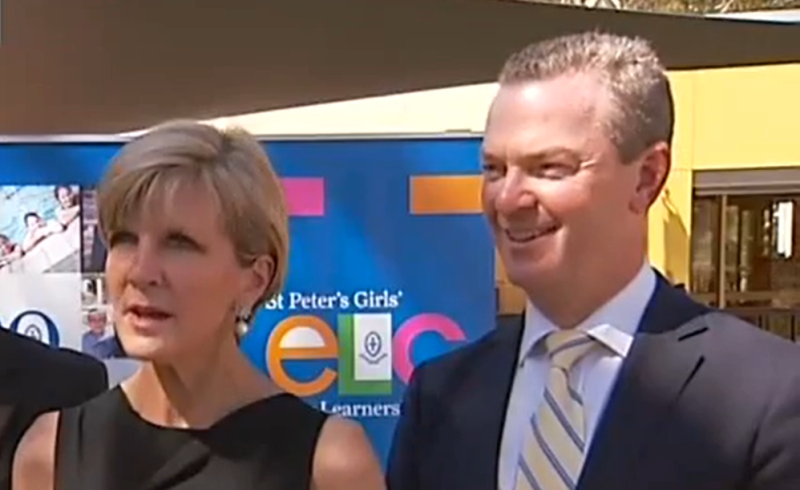

As Alan Austin recently observed in IA, a string of Liberal and National ministers, most recently Julie Bishop and Christopher Pyne, have gone to work for foreign corporations immediately after their retirement.

The same is true on the other side of the fence, and has been for many years. After deregulating the financial sector, former Prime Minister Paul Keating went on to a lucrative career as a senior adviser to (and now chairman of) Lazard Freres. Craig Emerson is an adviser to KPMG. Martin Ferguson works for the foreign-dominated Australian petroleum Production and Exploration Association.

There are plenty more where that came from.

We can expect more of the same in the future. In the most appalling application of section 44 to date, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg (born in Melbourne) is being challenged because of the possibility that his mother, a refugee from the Holocaust, might have been granted citizenship by a Hungarian Government seeking to make some atonement for this crime against humanity. The case now depends, to a large extent, on the goodwill of the current neo-fascist government of Viktor Orban.

It would be a travesty for Frydenberg to be disqualified on this basis. On the other hand, throughout his career, he has done the bidding of both Australian and foreign corporations at the expense of Australia’s national interest.

It is for this that he and his colleagues should be thrown out of office.

Reform measures, such as restricting the capacity of former ministers to work for corporations that depend on government policy might do something to mitigate the problems we face. But the real solutions are political. There was nothing surprising about the careers of the politicians mentioned above. Their post-political jobs followed naturally as rewards for the policies they pursued in office.

Only by struggling against such policies, and pointing out the corrupt interests behind them, can we preserve an Independent Australia.

You can read Professor John Quiggin's blog at johnquiggin.com and follow him on Twitter @johnquiggin.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.