A federal human rights act will encourage equality among Australians and begin the process of ending racism, writes Gerry Georgatos.

RACISM AS A WORD is intertwined with discrimination and denialism. The presumption of the ludicrous word “race” is coiled descriptively in the belief of distinguishable peoples committed to different experiential and systemic views.

We drink of remedy when we speak with words such as misoxeny and xenophobia. The Greek derivation of misoxeny reads as the hate of strangers. Xenophobes have a fear of the stranger.

During my first day at school in 1967, I did not know a single word of Australian English. The decade I was born into wounded and haunted me for decades thereafter. Oftentimes denying to myself racism, but indelibly stored in the recesses of my being.

Kahlil Gibran wrote:

‘Who knows but that which seems omitted today, waits for tomorrow?

Even your body knows its heritage and its rightful need and will not be deceived.’

Beginning my school years as an “alien”, I not only felt but was also made to feel different and very often unaccepted. Not long into my school experience, I realised some students, particularly many parents and some teachers, inherently disliked me because of the colour of my skin and because of my surname.

It did not matter who was kind or liked me. I was vanquished by the hurt of hate and wounds. Oftentimes it felt like I ceased to exist.

Migrants were expected to assimilate and acculturate or perish. Integration, as an applied word to imply a coming together, is a “bullshit” word.

I lived in the decorative portrayals of imperialism’s “White man’s burden” — where purportedly the British and the fringes of their Western European cousins claimed the mission of bringing civilisation to the rest of the world. I am reminded of the muddled-minded haughtiness of civilising claims of ‘new-caught, sullen peoples, half devil and half child’ described in Rudyard Kipling’s poem, ‘The White Man’s Burden’.

In fact, the imperialist British decimated civilisations, divided and fractured peoples and savaged them with wars and exploitations. The imperialist British remain the world’s greatest architects and builders of slums. Billions of tortured souls, from the cradle to the grave or pyre, have slum-dwelled since first contact with the decorated minions of Britain’s imperialist elite.

No nation peddling a dominant culture is free from the ugliest forms of racism. Privilege is a claim no one should want to own — it is exploitive and its intersectionality with so many -isms is abhorrent. Privilege, in its rawest self, is about relentless exploitation, but even in its greatest calm, it is about selfishness. In all its forms, privilege is an intended means of control — the assumption of power imbalance is too kind.

You are not just born into privilege, cognitively there comes a choice to live in privilege. Arguably, it is incumbent on everyone to disown privilege, to “lift” themselves out of privilege. Privilege is “institutional” and for many who do not understand “institutional racism” and “institutional poverty”, I am giving you an understanding of what we need to rise beyond. Let us speak of the sweetness of friendship.

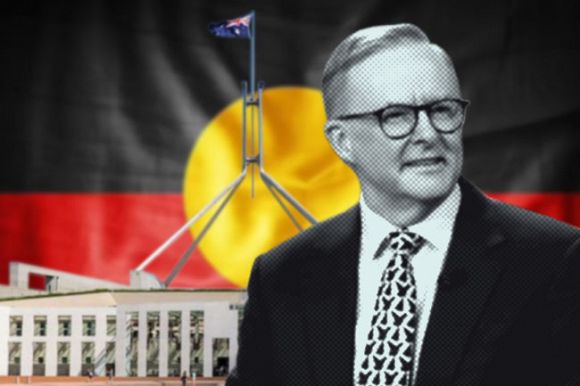

The Australian Constitution was scribbled together at a time of horrendous discrimination, of reprehensible racism. At a time when the invaders dished out eugenics, apartheid, segregation, exclusion of peoples and federated Eurocentric White Australia policies.

A federal human rights act will coalesce the Australian community closer together, reduce the risks of erosion of civil liberties and protect rudimentary human rights which we falsely take for granted and as if immutable. We can reduce racism and discrimination.

Without a federal human rights act, our nation remains hostage to the Kafkaesque, to deportations, to arrests and detainments without court warrants and without substantive grounds.

The eight states and territories must also have a jurisdictional human rights act, which cannot conflict with the federal one, but which is ancillary and extends to state and territory jurisdictional responsibilities such as correctional facilities and therefore the rights of the incarcerated. No one must be lost, no one alone.

A federal human rights act must protect the rights and make impermissible the Kafkaesque, for all citizens and all residents — special visa residents, permanent and temporary visa residents, refugees and asylum seekers. No one who walks this continent, no matter where they are from or why should ever become unseen and unheard.

I have been representing residents of many years living on this continent, some of who have Australian-born and bred children, who have had their visas revoked and are hence at risk of deportation. Relatively unaccountable bureaucrats and politicians bent by muddled-minded dogma playing out age-old racism.

A decade ago, I fought for up to 158 Indonesian children – the majority incarcerated in Australian adult prisons – while the remainder languished in squalid immigration detention centres littered across the continent.

Every human being should be protected in terms of their rights. Australia’s human rights record, on so many fronts, has degenerated contextually to its lowest ebb during the last quarter-century. A federal human rights act can repair Australia’s appalling record of human rights abuses.

Human rights and civil and political liberties should never be at the behest of any government but rather by referenda to the people.

The social good, the common good and universality should never be tenuous or frail because of a change of government. Without a human rights act, we are at risk of tyranny by government.

The common good in all of us aspires to an Australia with the world’s best human rights record.

No nation should be at the behest of populism and no government should be unaccountable. A human rights act commits governments to the common good. A comprehensive robust human rights act ensures a higher level of trust from the people than is the case in the absence of one. The work of government becomes clearer and monitored where there is a human rights act.

A federal human rights act can wind back the dramatic erosion of civil liberties during the last quarter-century, which has now diminished rights and privacy to the once unimaginable. Human rights and responsibilities are intertwined and are not separate as propagandists would have us believe.

The human rights act which I would be proud of is the one that ensures protections and inalienable rights to citizens, residents of all categorical types, refugees and asylum seekers. More than 40,000 citizens and residents are incarcerated in over 100 gaols and their rights should not be diminished once incarcerated. But sadly, this is what occurs.

Most Australians do not know that the incarcerated are denied Medicare and are not easily entitled to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and to the National Disability Insurance Scheme. The result is substandard health care – primary, secondary and allied – and unnatural deaths in custody, suicide, many coming out of the carceral experience worse than when they went in and many more suiciding or dying unnaturally within the first year post-release.

Many of us have been calling for prisoner rights for decades, not just limited to Medicare, the PBS and the NDIS.

The racism I felt in my childhood led me to reason about how many people we leave behind and how many people we betray. How should I live my life in light of the majority of humanity left behind and betrayed?

I have acquired my belief systems as to how I should live my life and to my suite of meanings. I am guided by the simplest wisdoms — goodness and fairness.

I want no ‘unearned assets’ as described by historian Peggy McIntosh, stolen from captives, the oppressed and marginalised peoples, or from the exploitive indenture of wage slavery. I do not want to be rich by others made poor. I have never wanted to climb the rung of ladders that disconnect me into barbarous ruling classes.

I do not strive for an extraordinary life but for an honourable life. Where we marvel at coming alive each day. Where possible, we support those who without support cannot achieve their best self.

I have found some of the most damaged people are the wisest counsel and the most empathetic. I have found many of them the kindest. Some of them are ultra-empathetic and transform lives because they do not want to see others suffer as they once did.

We stigmatise the poor, the homeless, the incarcerated and parents. We live with preposterous prejudices and criticisms of the poor.

There is no joy for me, no relief in writing of divides, inequalities, racism and of -isms. It has been endless. The calling out will continue long after my bones are soaked into the earth.

Rabindranath Tagore wrote:

‘The one who plants trees, knowing they will never sit in their shade, has at least started to understand the meaning of life.’

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus on social justice. You can follow Gerry on Twitter @GerryGeorgatos.

Related Articles

- FLASHBACK 2017: Drowning in White privilege

- Business leaders must step up to stamp out workplace racism

- Double standards stir racist-Australia comments

- Sickness of racism still alive in Western culture

- Harmony Day airbrushes Australia's racist ideologies

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.