Josefa Henriquez, Dr Manuel Garcia Goñi and Dr Francesco Paolucci detail how Spain climbed to one of the deadliest countries during the pandemic.

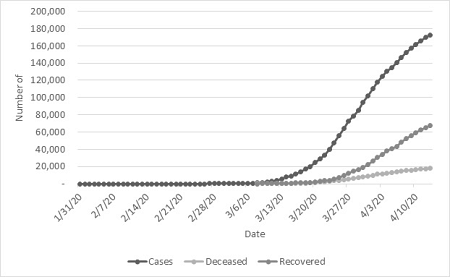

SPAIN HAS BECOME the nation with the second greatest number of cases of COVID-19 (177,633 as at 16 April) after surpassing Italy on 3 April, the previous epicentre of the pandemic (165,155) and currently ranking second after the United States. On 25 March 2020, nearly two months after the virus started in China, COVID-19-related reported deaths in Spain exceeded those of China. To date, the country ranks third in the number of deaths (18,812), after Italy (21,645) and the United States (28,573).

Nevertheless, the death toll and contagion curve have been consistently decreasing, providing a glimpse of hope. Since 1 April, the date in which the country had the highest number of recorded deaths in a day since the pandemic started (950 casualties), the number of casualties has decreased, currently at 567 casualties (13 April). Moreover, from 12 April to 13 April, a 1.79% increase of cases was observed, the lowest in the series.

Why did the situation escalate so quickly?

Some explanations behind the tragic death numbers can be traced to the nation’s population pyramid. The Spanish population has the highest life expectancy (83.4) in the OECD countries, above the average of OECD nations (80.7), as it is also a more aged country in terms of share of population over 65 (19.29 vs 17.204). This longevity comes with a significant rate of morbidity — 62.3% of people older than 65 live with two or more chronic conditions. Indeed, the COVID-19 fatality rate is higher among people aged 60 years and older (96% of the total deaths).

Pre-existent conditions show a high correlation with the cases as 67% of patients who are infected had underlying illnesses such as cardiovascular, respiratory, diabetes or hypertension.

Despite the later start compared to Italy, the cases in Spain and its fatality rate (deaths/total cases) has risen consistently over the evolution of the pandemic, currently at 10.5% (from 2.9% since the 100-death mark was surpassed) and lies among one of the highest in the top ten affected countries.

Was the Spanish healthcare system ready?

Health system resources play an important role in the response capacity of the countries and their success rate.

The Spanish health system was presented a per capita healthcare expenditure of U.S.$3,428 (PPP) in 2018, below the OECD average of U.S.$3,994. The economic downturn forced budget constraints and decreased public expenditure between 2010 and 2015, amounting to 0.9 points of GDP, while an increase has been observed since 2015. Yet private expenditure on health has risen. Health expenditures in Spain represented 8.9% of the GDP in 2018, around OECD numbers (8.8%).

Initially, Spain was not equipped to deal with the surge in cases. Beds per population were well below OECD average, at 3 per 1,000 people (versus the average of 4.7). Moreover, before 29 March, ICU beds totalled 4,545 while at that time, ICU patients reached 5,288.

The country had to quickly amend this. To date, ICU capacity has more than doubled in several regions in Spain, currently at 7,842 (a 75% increase).

Regional differences in Spain play an important role and countrywide generalisation does not paint the full picture. The most affected region in Spain is Madrid (~6.6 million people) with 48,048 cases and 6,568 deaths by 13 April. Nevertheless, Madrid was ahead of Catalonia and other regions by a few days in the number of cases and deaths.

Despite Madrid having the highest regional number of ICU beds (800) before the pandemic, the sharp increase of people with severe disease saturated the capacity of the region which was forced to increase the number of beds available by 925, an increase by 115.6% of the ICU capacity. At the same time, it is significant to note that a provisional hospital was opened in Madrid on 21 March at IFEMA (Feria de Madrid) that could accommodate up to 5,000 beds (and up to 500 ICU beds) if necessary. Catalonia also announced on 30 March the opening of another at the Fira de Barcelona that would start with 300 beds and, if necessary, could reach a capacity of over 2,000 patients.

Due to the slight delay in the evolution of the disease, as of 29 March, Catalonia (1,512) surpassed Madrid (1,460) in the number of people in ICU. On 13 April, Catalonia held 2,775 patients in that condition, over its theoretical capacity, while in Madrid the number of people in ICU has lowered to 1,299.

With the spread increasing, not only physical resources had to be increased but the health system had to deal with an increasing number of its health workforce being infected, as of the latest reports of around 26,672.

This has led to a series of conditions previously in place related to contracting of medical staff, retirement, resident doctors and graduation of health professionals to be relaxed to deal with the demand.

Since the first case of COVID-19 was attributed to a German tourist in La Gomera Island on 31 January, contact tracing has been soft and mainly registered in broad categories as:

- contact with an ill person;

- travel to Hubei;

- strict contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case; and

- visit to a health facility, medical worker, or contact with an animal, according to reports issued by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

The Spanish Government didn’t have initial capacity of testing and restricted lab work to under two situations: patients presenting acute respiratory infection who are hospitalised and those in the health and social care workforce or any other essential service (policy, military force). Testing until the middle of March had been 30,000.

While the situation was worsening, authorities had to be quick and increase testing capacity, informing that a week later, on 22 March, 355,000 tests had been performed, with a daily capacity of 15,000 to 20,000 tests. Additionally, the Ministry of Health purchased 640,000 rapid detection antigens and set to purchase another 5.5 million more, including four robots for testing automation.

After a sequence of policies (9 March: schools and universities were closed when a community outbreak was declared; 10 March: direct flights to and from Italy were suspended), it was only on 14 March that Spain declared the state of alarm, limiting people movement to grocery shopping, pharmacy and work attendance. This came nearly a week after Italy imposed a nationwide lockdown on 9 March. By that date, there were already 285 reported deaths in the country.

By 24 March, 926 people had been detained and 10,200 people had been denounced for non-compliance of the state of alarm issued by the Government. Until 10 April, more than 3,000 drivers had been sanctioned for not respecting the movement limitation imposed.

Is Spain back on track or are exit strategies premature?

The economic impact of the virus was addressed early on by the Spanish Government. It made available €600 million for vulnerable families, €102,000 million for business, €30 million for CSIC and Instituto de Salud Carlos III for COVID-19 research.

Currently, the sociopolitical debate is on how to design the return to normality for the population in a staggered manner so that it impacts the country's economy as little as possible. More so, taking into account that different regions have been affected differently and, as in the case of comparisons of different countries, some regions are a few days ahead (or behind) with respect to the evolution of the epidemic.

It has become evident that with the Spanish bumpy start, restrictive measures that moved fast into extreme draconian ones have paid the dividends. As of Monday 13 April, working restrictions to non-essential workers (whose work activity cannot be carried out at a distance, through telematic methods) have been lifted and thousands of workers returned to work. Additionally, the Government has issued several safety recommendations and it is giving free masks at key transport locations such as subway stations.

Meanwhile, citizens are still obliged to stay home until 26 April, although it is still uncertain, at this point, whether this mandate will be further extended.

Josefa Henriquez is an economist currently working as a Research Fellow at the University of Bologna in Italy on the European Horizon 2020 funded MCDS Therapy economic research group. Manuel Garcia Goñi is Professor of Applied Economics at Complutense University of Madrid. Francesco Paolucci is Professor of Health Economics & Policy at the Faculty of Business & Law, University of Newcastle and the School of Economics & Management, University of Bologna.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.