If we take lessons from history, we can use this chance to emerge from the pandemic with a world changed for the better, writes Dr Robin Tennant-Wood.

TIME. That’s the gift of the COVID-19 coronavirus. For many of us, time has become a blur of bouncing from one commitment, one activity, one engagement to another meeting, task, arrangement. A constant stream of busyness in the pursuit of… what, precisely? Money? A better future? Happiness?

“I don’t have time to read.”

“I don’t have time to do the gardening.”

“I don’t have time to exercise.”

“I don’t have time to walk the dog.”

“I don’t have time for a hobby.”

“I don’t have time for reflective thinking on where humanity is heading and whether I want to go that way.”

Most of us won’t die of COVID-19. With careful management, self-isolation and social distancing, it’s possible most of us won’t even get it. What a lot of us do have now, that we didn’t have a few weeks ago, is time. As workplaces shut down, people work from home, children stay home from school and people go into self-isolation, we’re finding ourselves in an unfamiliar place: our own homes and our own heads.

For a lot of people, this will mean hardship. Many will lose jobs and income. The arts, in particular, have been hard hit as concerts, theatres, galleries close and events are cancelled. Some of the country’s most loved orchestras and theatre companies may go to the wall, depending on how long the health crisis lasts. But there is opportunity for innovation lurking behind the curtains of uncertainty.

Our current global health crisis is not (despite chronic overuse of the word) unprecedented. There have been pandemics before and the human race has survived them. Importantly, in each case, they changed social and political direction.

In Barbara Tuchman’s ‘A Distant Mirror’, a detailed examination of 14th-century European society, the author details the plague years during which the (European) population was reduced by up to 50 per cent. After the plague, life rebalanced, but, crucially, didn’t return to pre-plague “normal”.

The post-plague era saw the emergence of a middle class as many peasants were able to claim and occupy land vacated when landowners fled or died. This was also the beginning of the secularisation of education as a result of losses among the clergy, which was solely responsible for the education of boys. The Church attempted to resolve the issue by quickly ordaining more priests, but many of these new clerics were illiterate. Attendance at the great universities – Oxford, Bologna – dwindled and for the first time, non-clerical teachers appeared as education took a new direction.

The Spanish flu pandemic that killed millions of people in 1918-19 resulted in numerous uprisings resulting from the perception that the virus and its high mortality rate was due to social inequality. It also changed the way many Western countries approached public healthcare.

British science journalist Laura Spinney writes:

The 1920s saw many governments embracing the concept of socialized medicine — healthcare for all, free at the point of delivery. Russia was the first country to put in place a centralised public healthcare system, which it funded via a State-run insurance scheme, but Germany, France and the UK eventually followed suit.

A century later, we have advanced medical knowledge and our standards of public and personal hygiene are higher than in the average 14th-century city or town. We also have the means of instant communication and information technology. But what COVID-19 has in common with previous pandemics is that there will be no return to “normal”. We get to create a new normal.

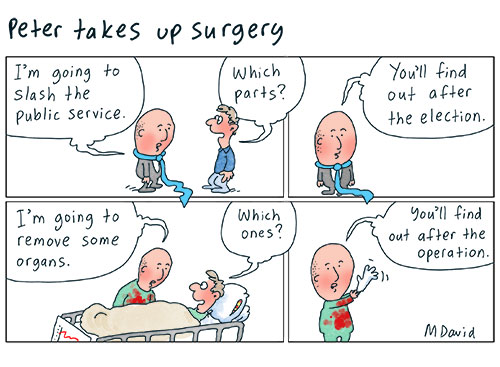

The coronavirus has hit the pause button on humanity’s mad rush towards the cliff.

What if schools closed down for six months? What if they remained closed for the rest of the year? Would that necessarily be such a bad thing?

Even in situations where parents or carers are unable to work from home, would it not be possible for children to attend school where teachers could instruct small groups in activities like gardening, cooking, basic mechanics, bike maintenance, arts and crafts, music, a sport or recreational activity? Not formal classes, but informal instruction in whatever teachers are themselves good at or interested in.

Online classes and homeschooling could ensure continuity of formal education but what else might children have time to learn that the daily routine of school simply doesn’t allow for? Education is not the sole preserve of the classroom. It is possible that by hitting pause on schooling for the rest of the year, we might end up with better educated and well-balanced kids. The school system teaches them to adhere to strict routines and to compete against one another and while these may well be relevant skills for the “real world”, maybe a post-pandemic “real world” could be less time-constrained and operate flexibly and cooperatively.

Education policymakers and teachers alike would benefit from the opportunity to cooperate to design an education system for a sustainable future instead of one based on the past which has simply been adapted for new technology. Instead of educating children and young people to occupy “jobs” – the concept of which has changed little since the Industrial Revolution – use education to help them create their own vocations.

Online and physical retailers of seeds and vegetable seedlings have reported unprecedented (that word again) increases in sales as people look to their backyards as a source of food. Backyard poultry is also seeing a huge surge of interest. Children whose parents have never had time for gardening might, for the first time, learn to grow food and care for chooks.

Our concept of work will change. How many people are now working from home who, for years, have commuted without question to offices and other workplaces? How many jobs can be undertaken efficiently and flexibly via the incredible technology we typically to use to play games, look at pictures of cats and get into arguments with strangers?

If a secular education was the legacy of the 14th-century Black Death and nationalised healthcare that of the 20th-century Spanish flu, we have time now to consider how we can ensure a positive social legacy from 21st-century coronavirus. We owe it to those who follow us.

Dr Robin Tennant-Wood is a former lecturer in political science at the University of Canberra and freelance writer and researcher. You can follow Robin on Twitter @rtennantwood.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.